An Unforgettable Pilgrimage in Spain: Climbing to the Birthplace of Reconquest

Three days of prayer, penance, fellowship, and fulfillment

At the end of last month, over the three days of July 26-28, I took part in the fifth annual Pilgrimage of Our Lady of Christendom (Peregrinación Nuestra Señora de la Cristiandad), which begins in the ancient city and episcopal see of Oviedo and ends at the shrine of Covadonga, built to commemorate the victory of King Pelayo over the Muslims in 718, which is seen as the start of the Reconquista of the Iberian peninsula, as the Muslims were driven out slowly over the course of the next eight centuries until their final defeat in Granada.

It was a splendid pilgrimage. I am so glad I went on it, and I would encourage everyone out there who would like to do a “Chartres-style” pilgrimage but without the downsides of 20,000 people to give this one a try.

By no means is it easy to write about an experience that was so immersive, so total while it lasted, that you felt as if you had become identified with your aching feet and tired limbs, as if you had enlisted in an army of resistance, as if you had thrown away the scales by which modern man carefully weighs utilities and values. And then there is the pressure to write “great thoughts” where perhaps you have only vignettes wrapped in a silent sacred purpose. Living in the moment, wondering when the next break will be, weaving in and out of endless conversations about things great and trivial, singing hymns and chants, praying decade after decade of the rosary, and animated all the while by the intentions for which you are walking this little Calvary — so personal that you could never share them.

We walked sixty miles over those three days. As you’ll see, we went through some of the most beautiful countryside in the Asturias.

I walked with the American chapter, led by my friend Jeff Inferrera. Here we are together. The sign says “stop” but we never stopped!

A note on the pictures: Most of the photos in this article were taken by me, but some are courtesy of the official pilgrimage photographers, and some are from Jeff. If you want to enlarge any image or gallery of images, click on the title of this article in your email — that will take you to my Substack’s page online, and there you can interact with the images.

The Day Before

The Oviedo-Covadonga pilgrimage always falls on the Saturday, Sunday, and Monday nearest to the feast of St. James, Spain’s great patron. This year, July 25 fell on a Friday, so I drove that morning from León, where I’d spent the night, to Oviedo.

Jeff had explained to all of us that we needed to bring meat and cheese in our packs for lunch, as the pilgrimage volunteers would only be handing out bread and water. So, the first order of business was buying supplies for the knapsack. I took a walk in the old city center and happened upon a local fresh market. The fish stands reminded me of how different it is to live near the sea:

I picked up sausage and cheese, and headed to a specific address to meet Fr. José Miguel Marqués Campo, with whom I had long carried on an online correspondence. Fr. Marqués is the Latin Mass delegate for Oviedo and he met me in order to lead me to the chapel where the High Mass would be offered for the feastday.

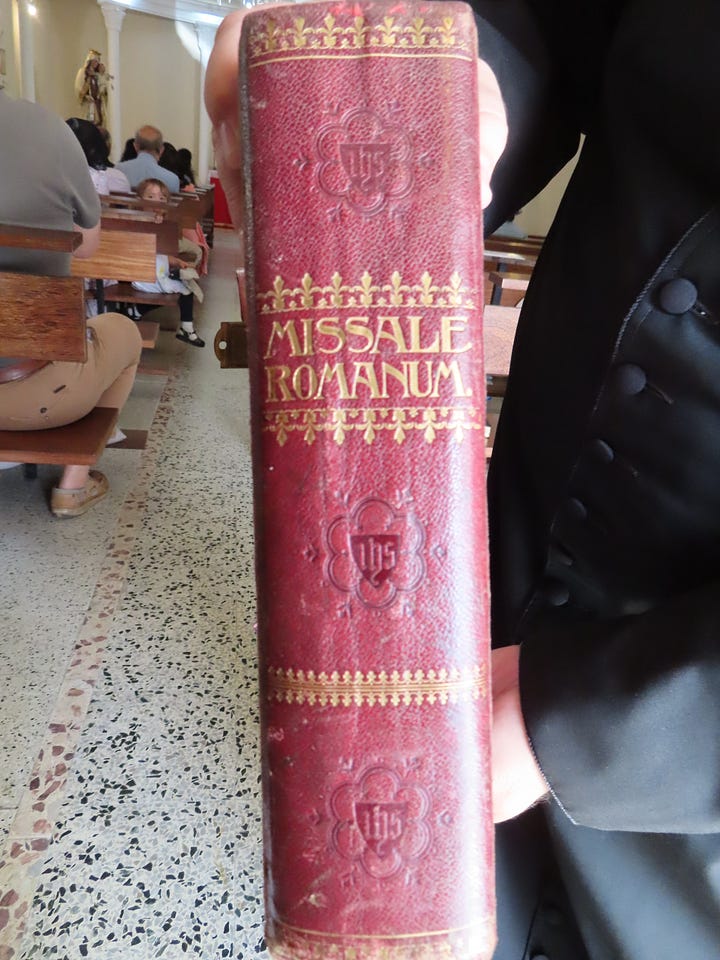

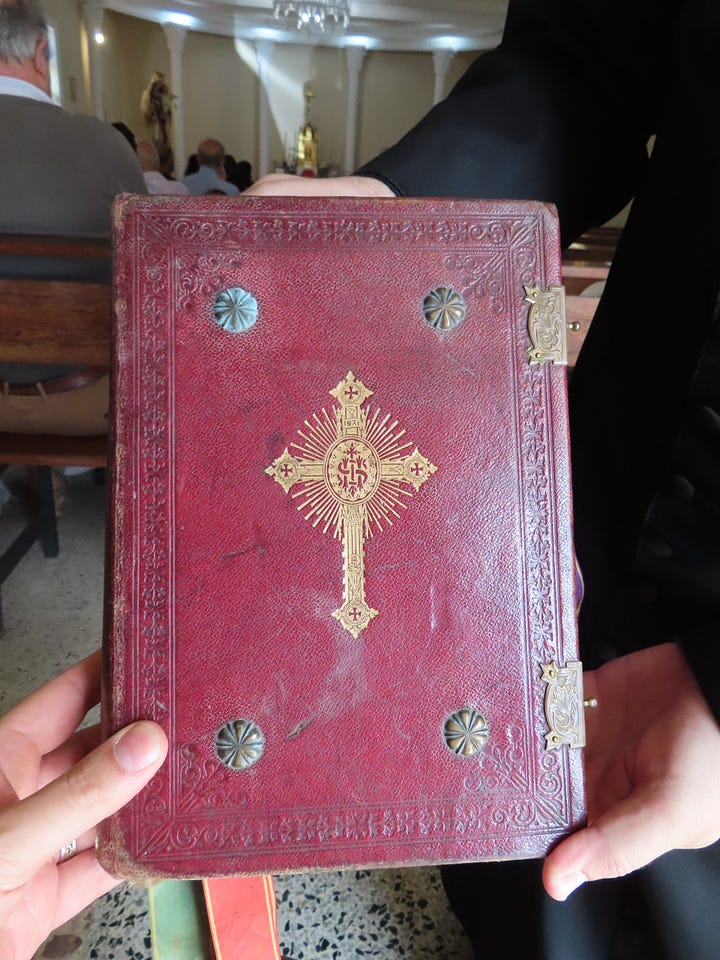

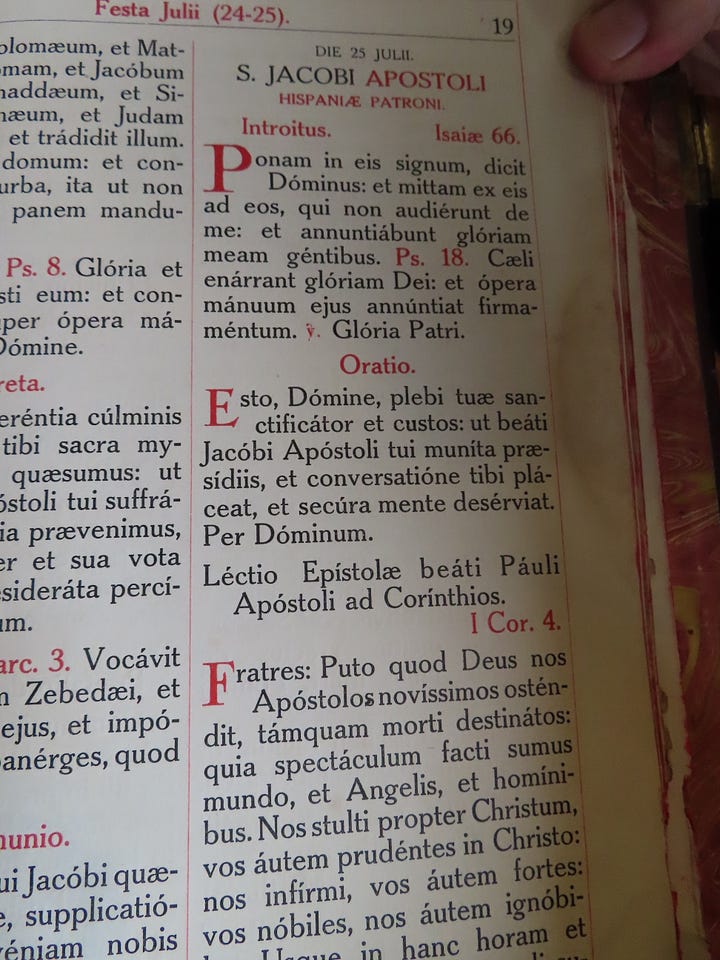

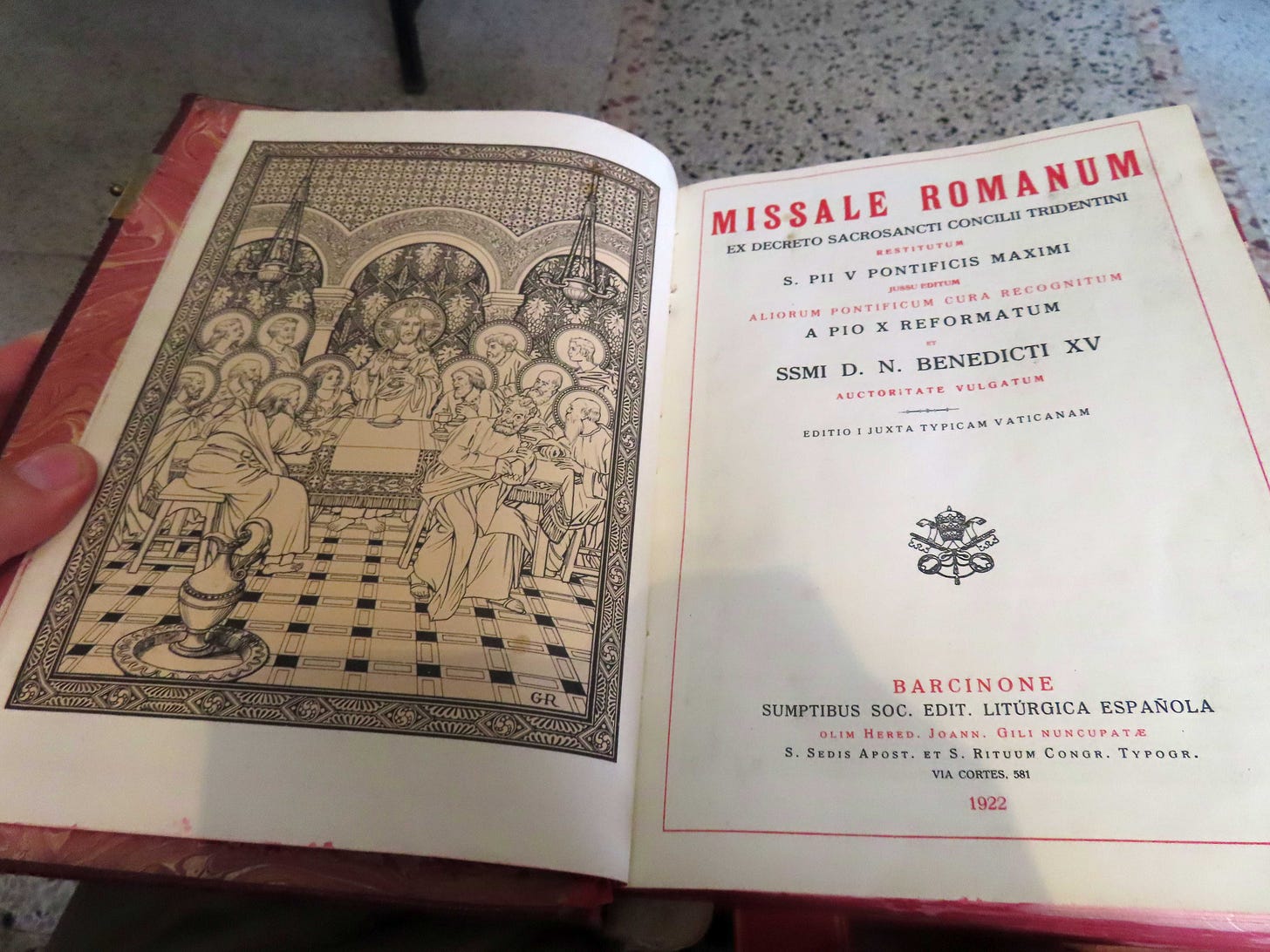

We arrived and he proudly showed me the handsome 1922 missal he’d be using:

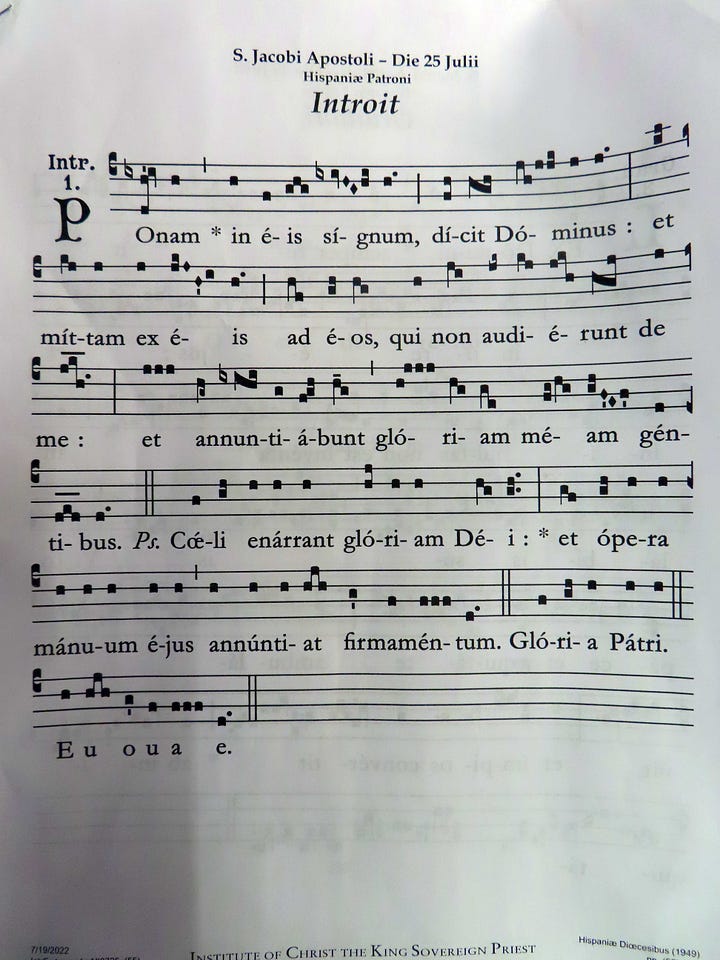

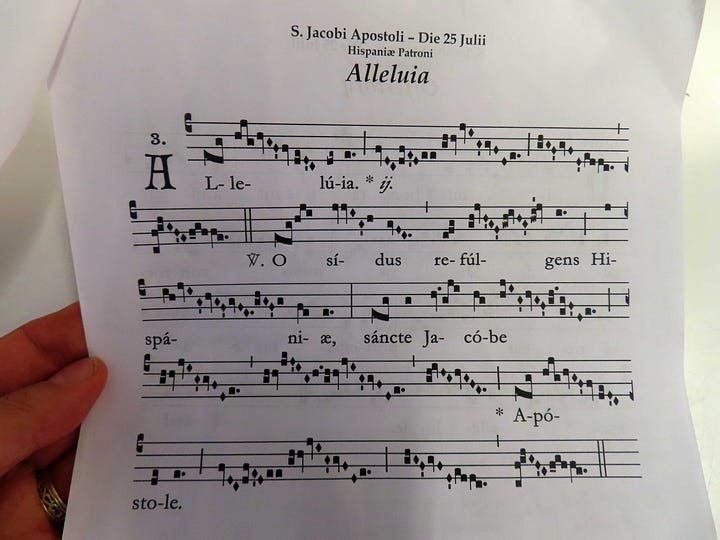

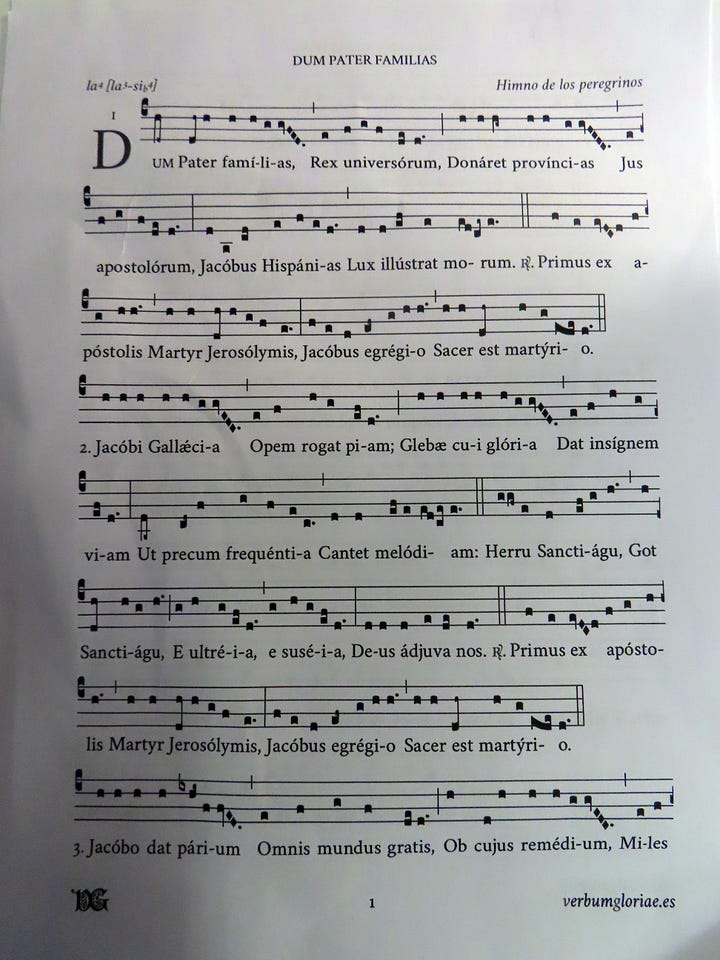

I sang the chants for the Proper Mass, which are really splendid (and can only be used in Spain!). The little choir sang a pilgrimage hymn to St. James during Communion time; its text was quite intriguing:

A few photos from the Mass:

After lunch, Fr. Marqués and I made a short visit to the Cathedral of Oviedo (which you’ll see in a moment). In the evening, I gave a lecture at a hotel in the city center, which was attended by somewhere between 150 and 200 of the pilgrims. It was a full room. Then, dinner, and to bed.

The First Day

We were under strict orders to report to the square in front of the cathedral by 6:30am. When I later discovered that the opening ceremony didn’t start until 8am, I’ll admit to feeling cheated out of an hour’s sleep, but I guess when you’re trying to mobilize 1,500 pilgrims (that was this year’s number), you set very generous time expectations.

Here you can see the single tower of the cathedral, and the gathering crowd:

The American chapter, named in honor of St. Kateri Tekakwitha:

Msgr. Marco Agostini, a well-respected long-time papal MC, joined us from the Vatican for the entire pilgrimage (he walked in a beat-up black cassock, not in his finery!). He offered the Solemn Mass on the Sunday. Here we are in the square just before the opening ceremony:

Inside the cathedral we gathered in front of the impressive reredos — in Spain, every cathedral seems to vie with every other for the glory of its high altar:

The clergy processed in:

The bishop presided and welcomed everyone quite warmly. After the traditional Itinerarium prayers for a safe journey were chanted, the bishop walked down the aisle sprinkling the pilgrims with holy water:

The first ones privileged to carry the image of Our Lady of Covadonga — she would be carried the entire 60 miles, with a good many “changes of the guard” — were seminarians:

The St. Kateri chapter always walked after the Our Lady of Walsingham chapter from the UK, and in front of the chapter from Italy, which never stopped singing (and a lot of it, most definitely not “PC”)!

And the walking began…

and continued, sometimes with equine neighbors:

until a welcome break:

Many hours later, after a second break for lunch, we reached our campsite, a large (privately-owned) field nestled next to a handsome little Catholic church. Not only was this remote country church open for prayer…

…but its porches gave hospitable shelter to ranks of priests offering their daily private Masses, in a sight that never ceases to move me deeply:

Let me pause a moment to say a word about this custom of the daily private Mass (when a priest has no other pastoral obligation) instead of concelebration. The first thing we must understand is that, so far from being some sort of “medieval corruption,” the private Mass arose very early on in Western Christianity, as Canon Gilles Guitard explains in a superbly researched study (Part 1, Part 2). It remained foreign to the East, but there are many real and profound differences between East and West that cannot and must not be put down to one being wrong and the other right.

In a similarly luminous study, Bishop Athanasius Schneider discusses how concelebration was foreign to the Western tradition (with the solitary exception of the partial concelebration that takes place at the ordination of a priest or a bishop) until it was artificially foisted on priests in the liturgical revolution.

For a simple explanation of why private Masses such as those seen in the picture above are appropriate, read this; and for an explanation of why no bishop in the world can forbid a priest from saying a private Mass (including a private traditional Latin Mass), read this.

On a pilgrimage like this, you carry on your back only a few pounds of essentials. The rest of your gear is put into a duffel bag in the morning and driven in a truck to the campsite. The duffel bags are set out on the ground in groupings and you simply go and find yours and bring it to the tent.

Once all the pilgrims reached the campsite and had an hour or so to rest their weary bones, Solemn Mass was held in a large open field, with a tent over the improvised sanctuary. What I like to say about the stops along the Chartres pilgrimage is no less true of the Covadonga one: the makeshift chapel is more obviously Catholic than thousands of churches built after Vatican II — to say nothing of the awesome rite of sacrifice offered under its shade!

The loving care with which Holy Communion was distributed to so many pilgrims was exemplary. Priests who went forth to distribute Communion were always accompanied by two assistants: one layman holding a white umbrella over the ciborium — not only as a sign of reverence (as we see when the Blessed Sacrament is transferred in a church using the ombrellino), but also as a way to see very easily where a priest is located, which is helpful in a large number of people spread out over a field — and a gloved altar server holding a communion plate to hold under the recipient’s chin:

What this demonstrates is that “if there’s a will, there’s a way.” The casual and sacrilegious treatment of the Blessed Sacrament at World Youth Days could be avoided — if they cared… if they believed.

Needless to add, confessions were being heard almost around the clock:

After the Supersubstantial Daily Bread, grumbling tummies demanded attention! Meet the ubiquitous natural daily bread. Breakfast was a piece of baguette and some jam, with a cup of coffee. Dinner was a piece of baguette and a cup of soup. Lunch was… a piece of baguette with whatever you happened to bring in your knapsack. Here’s a familiar sight:

The Second Day

A cool and misty morning, welcome to everyone. The weather was gorgeous the entire weekend: generally cool, often with a breeze from the mountains, and only a little rain on the last day.

The countryside fed the contemplative soul with its beauty.

In this picture, taken walking backwards, you can see the long line of pilgrims winding up into the distance.

The locals were always very friendly, often standing on their porches or at their windows and waving to us.

I’m sure this is more excitement than usually happens in some of the sleepy hamlets we passed through.

The flags, banners, and crosses lifted the heart.

Two things made the many hours pass by quickly: (1) continual conversation with one’s neighbor of the moment — I had the chance to talk not only to fellow Americans but to people from, as I recall, the Netherlands, Sweden, England, Scotland, Poland, and Mexico; and (2) frequent rosaries and songs. Whoever came up with the Ave Maria of the Chartres pilgrimage is a minor genius. This is perfect marching music:

As is proper to an oral tradition that most people know without having seen the musical notation, there seem to be some variants in how the melody is sung. In particular, on “benedicta tu,” I have heard a fifth (D to G), a fourth (C to G), and a minor third (Bb to G). For what it’s worth, singing a fourth makes the most musical sense to my ear, as picking up from the “te-cum.”

Our Lady of Covadonga accompanied us all the way:

Our path took us once again past an old country church — it is impossible in Europe to go very far without stumbling across a monument of devotion — and its cool interior invited a moment’s repose.

Moving toward our evening campsite:

A wide but slow-moving river adjacent to the campsite afforded opportunity for men and women to bathe (in separate groups about a half-mile apart — everything on this pilgrimage was so well-planned!). I found the effects of cold water on my feet to be well-nigh miraculous:

And, under the humble tabernacles in the wilderness, the quiet hum of the eternal sacrifice on the lips of the icons of Christ resumed, raising up the cry of mankind and calling down supernal mercy…

The solemn Mass was offered by Msgr. Agostini, the Vatican MC. Here, he reads the Epistle silently while the subdeacon chants it:

At the consecration, men bearing flags for the regions of Spain — you can see Asturias, Castile and León, Navarre, Aragon, Valencia, Catalonia, Galicia — processed and knelt as an honor guard.

The Third Day

By this time, I think it’s fair to say, there are two dominant feelings among those who have made it thus far: (1) thanks be to God I’ve made it this far, (2) how much longer have we got to go on before the end?? At the same time, I found, as most people do, that by Day 3 you’ve gotten into your stride, and the steps come without as much difficulty as they did on Day 1.

There was never enough sleep…

Our day started well before dawn, with solemn Mass “frontloaded,” since the bishop — yes, the same one who welcomed us and sprinkled us with holy water — refuses to let the pilgrims have the TLM inside the basilica of Covadonga, citing Traditionis Custodes. All the Masses therefore take place outside of churches, from start to finish, from Oviedo to Covadonga.

To me, this gives the pilgrimage a taste of “rebels for the common good,” like the Vendeans against the Parisian revolutionaries. Whether we like it or not, the traditionalist pilgrimages, with Chartres as their poster-child, are counterrevolutionary events: they stand as a resolute witness to the vitality and fecundity of traditional Catholicism against the entire postconciliar construct, the “new Pentecost” and the “new springtime” and the “new paradigm” and all that mumbo-jumbo. We would rather be outcasts living from heavenly treasures than company men slapped on the back for “obedience” as we look around at empty churches and dying dioceses.

Truly, I believe the day will come when traditionalists will be thanked for having remained stubbornly faithful; they will be hailed as the ones who jealously preserved tradition during a sore bout of spiritual amnesia on the part of officialdom.

As if to prove the point I was just making, even before the crack of dawn, dozens of priests, in spite of aching muscles and lack of sleep, were dutifully at their altars whispering Te igitur, clementissime Pater… As if nothing and no one could restrain them from rushing to the Father, begging for the Son, begging for themselves and the whole race of Adam.

These priests are wearing red because Low Mass was for Saints Nazarius, Celsus, and Victor I, Martyrs, and Innocent I, Confessor — one of those wonderful odd bundles of obscure saints that you get in the Tridentine calendar. At the public Mass, however, the vestments were gold because a Privileged Votive Mass of Our Lady of Covadonga was offered, before the pilgrims began their march to her shrine.

I love this photo, where the elevated chalice “coincides” with the statue of the Virgin of Covadonga. Our Lady is like a chalice, an immaculate vessel holding Jesus Christ, making Him available to mankind. She is the Seat of Wisdom who presents Him to us.

In full daylight by the time of the Last Gospel.

Then, trudging away again, behind the patriotic Brits!

The road goes ever on and on…

More horses.

Crossing a bridge in the town of Cangas de Onís, which was the capital of Asturias for King Pelayo before it moved to Oviedo in the late 8th century:

I must say, it was a lot of fun to pass through a sizable city because we got a lot of stares and smiles. This is a good public witness: we weren’t in anyone’s face, arguing or shouting; we were just doing our pilgrimage, with our rosaries and flags, on the way to Covadonga. I had the sense that it was a welcome sight to many.

I’d been forewarned that the final climb up the mountain to the basilica would be deadly, but honestly I didn’t find it any worse than the rest of the hike. If anything, the “horse smelling the barn” effect kicked in and gave renewed energy.

The first sight of the basilica was thrilling!

Just a brief word about the history of this shrine. The reason the spot is famous is that the aforementioned King Pelayo, vastly outnumbered by the Muslims, hid in a cave, praying about what he should do; and the Virgin Mary appeared to him, saying he should boldly go to battle, for God would fight with him and for him. Pelayo fought the superior Muslim forces and resoundingly defeated them, marking (as I said before) the start of the Reconquista of Spain. The cave in question is not too far from the basilica:

In order to pay homage worthily to the Virgin of Covadonga and to commemorate King Pelayo’s victory, an impressive basilica was constructed between 1877 and 1901 in a neo-Romanesque style:

Its location is quite stunning:

Pilgrims swarmed in the courtyard, overjoyed and relieved:

Not everyone could fit inside the basilica, but I managed to slip in and find a seat. The concluding ceremony, since it couldn’t be a Mass (alas), took the form rather of a grandiose Eucharistic Benediction: first, a sermon on Our Lady and a Marian consecration; then Exposition with a Pange Lingua alternating between chant and polyphony; then a chanted Litany of Loreto; a Te Deum in thanksgiving, again alternating between chant and polyphony; the Tantum Ergo with Benediction (both indoors and outdoors, for the pilgrims in the courtyard); and a rousing Spanish hymn to cap it off.

Afterwards, everyone poured out into the courtyard for a final group picture. It was rather difficult to fit everyone into it! Here’s a fair sampling. You can see me way on the left side:

And one more picture of the basilica’s lovely facade:

Thank you, Lord, for this pilgrimage! Thank you, Mother Mary, for watching over your tired and thirsty children. Thank you, King Pelayo, for listening to Our Lady and kicking off the Reconquista. We need another king like you… a “return of the king.”

Are the Elders Listening?

Why do we go on pilgrimage? And why are nearly all the popular pilgrimages today traditionalist ones?

I can’t think of a better answer to these questions than the one provided by Rod Dreher, who wrote recently at The Free Press about the significance of the Chartres pilgrimage (and others like it, such as Covadonga). Here’s what he says:

The reasons for the quiet revival of Catholicism among the young vary, but they all come down to the search for meaning, purpose, stability, and identity. These new converts—or “reverts,” for the baptized who have rediscovered their faith—are drawn to ancient forms of Christianity because these traditions are more rooted, and more demanding, than the looser, therapeutic model of contemporary Christianity. They also rely much more on liturgy and beauty to incarnate theological principles... These things have stood the test of time....

The Chartres pilgrimage, then, can be read as a mass youth protest against gyrovaguery, a physical and spiritual act to reclaim the pilgrim’s vision, against the tourist mode of life.... Young people, as natural progressives, are not supposed to want to recover what their elders tossed in the trash bin; they are supposed to want to free themselves from the dead weight of the Catholic past. “I think these are just fervent young people who don’t recognize themselves in what the bishops usually propose to them,” John Pepino says.…

Catholic traditionalism offers the young an opportunity to reclaim what life in modernity has taken from them. “Many describe the homilies in traditionalist parishes as more profound, less anecdotal or performative than what they’ve encountered elsewhere,” Maria-Katrina Cortez explains. “Many young adults who are mentally exhausted by the modern world find in these places a form of rest, rootedness, order, and mercy.”

In an article from November 2024 at this Substack, I quoted the Rule of St. Benedict, where he twice insists that the young in the monastery should be carefully listened to, because God often reveals to them what is better:

Being on this pilgrimage gave me a lot of hope and joy. I had spent about eight days in Spain prior to the pilgrimage, and at some point during those days, I wrote to a friend:

Spain is a gorgeous country, but I have more than usually the melancholy sense of walking through the remnants of a once-great civilization whose present-day heirs are utterly disconnected from it (and, in that sense, unworthy of it, indeed often enough explicitly antagonistic towards it). It made me reflect again on the strange situation of the USA: it is such a young country that it has relatively little history to speak of, and is fairly “empty” of content, which makes it all the easier to see Catholic tradition as a mighty revelation of meaning — as if one is hearing the message for the first time.

He replied:

I do not doubt it. To be someone who has more or less successfully initiated himself into his own spiritual and civilisational inheritance is to possess a source of immeasurable joy, but it is also to live henceforth with the pain of being an alien in this modern world, seeing all its maladies among those blind to every one of them. That is no small agony.

Yet when I joined 1,500 devout and fervent pilgrims, most of them Spanish, I realized that the embers of faith are still glowing in this part of Europe. Christendom is not dead, she only slumbers.

Wake Up and Smell the Incense

In imitation of its big sister, Notre-Dame de Chrétienté, this Spanish pilgrimage is dedicated to “Our Lady of Christendom.” Why that title?

Christendom is nothing but Christianity fully lived and therefore radiant in all aspects of life, including cultural and political. No serious Christianity exists that does not (or would not, if given the chance) blossom and bear fruit in the form of Christendom.

Not to desire the restoration of Christendom would be not to desire the full expression of Christ in His creation. Obviously, the individual Christian’s pursuit of sanctity is his primary obligation, but in pursuing it he necessarily benefits others; and when many pursue it together, the effects are not only personal but social.

Now, the restoration of Christendom will come in two ways primarily: through the high altar and through the marriage bed. If you want to see Catholic civilization reborn, do one or more of the following (some are incompatible but all are indispensable):

1. Get married and have a large family. Homeschool, with low tech. Have a garden or a farm and some livestock, and/or cultivate the arts, e.g., poetry, singing, dancing.

2. Become a priest and offer a traditional liturgical rite; be an active and zealous footsoldier for the reconquest of the Church in the name of tradition.

3. Become a religious whose life revolves around the offering of praise and petitions in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and the Divine Office.

If enough Catholics do these things, Christendom will begin to return, here and there, first in small patches, like the early spring flowers pushing through the snow, and later in swaths of assimilation, like the Reconquista of Spain.

Final Thoughts

The Covadonga pilgrimage was indeed a test of endurance and fortitude. After a couple of hours, each step was difficult, and there were times when one wanted to throw in the towel, especially with steep upward paths over and over again.

But being with all the other pilgrims, singing, praying the rosary, and long conversations had a way of making the time pass. One simply kept going along with everyone else, like beasts of burden that plow the fields. My three special intentions for the pilgrimage were frequently on my mind.

I can recommend this pilgrimage without qualification. If you are looking for a pleasant walk, a comfortable time, a good night’s rest, good food and drink, all the usual conveniences people take for granted, look elsewhere. But if you want a hard and painful hike to offer up, an experience of camaraderie in the midst of challenge, a deeper experience of the Church’s universality, an invigorating witness of youthful zeal for tradition, then by all means come on pilgrimage in the land of St. James and King Pelayo.

Thank you for reading, and may God bless you!

Wonderful account with gorgeous photos. Than you for sharing your pilgrimage with us!

Dr. K, thank you for all the hard work, giving six lectures in six different cities in Spain, back to back, and then doing the three day Pilgrimage to Covadonga, probably with a good dose of jet lag during and/or after. So you are smart and TOUGH too! King Pelayo would be proud.