Culture and Faith—Can They Flourish Apart from Each Other?

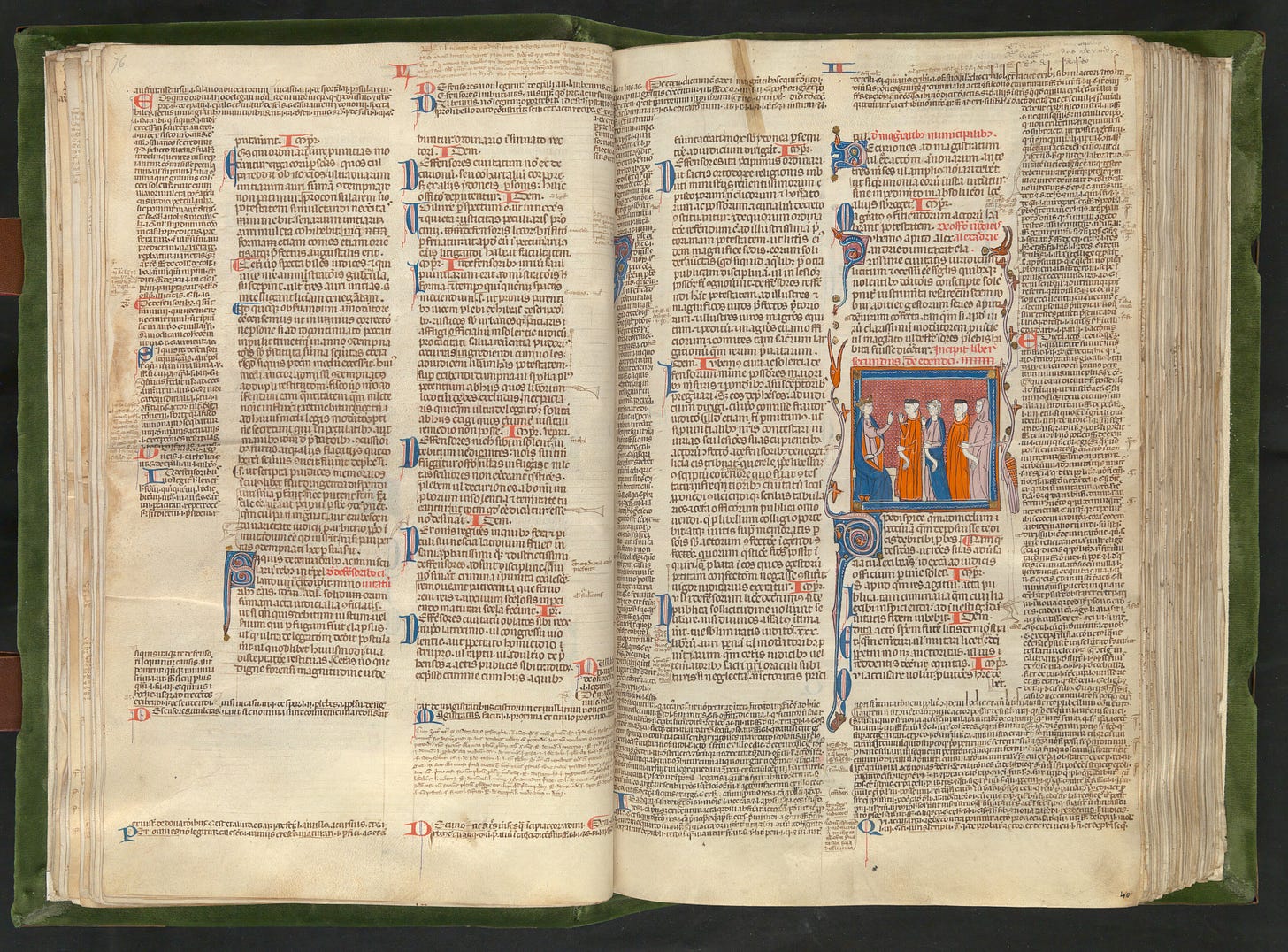

Early in his slide into heresy, Martin Luther commissioned the printing of a Latin Bible without the ‘Gloss’, a commentary that at the time was usually printed in the margins. He wanted to interpret the text without preconceptions.

It is true that commentary comes, in a certain sense, between the reader and the original text, and influences the reader’s understanding of the text, often decisively — indeed, that’s the whole point. This is a good thing if you have a degree of confidence in the tradition of interpretation that the commentary represents.

Then again, an attempt to read Scripture without any guidance at all has to grapple with the problem that no text is self-interpreting: if you reject one interpretation, you are going to need another.

The contrast between the naked words of Scripture and Scripture plus the Gloss has a parallel in the debate about faith and culture. Just as, over the centuries, the Catholic Church fostered a rich tradition of scriptural commentary, so it has fostered a tropical growth of religious culture, comprising devotional art, music, architecture, schools of spirituality, methods of prayer, religious dress, festivals, and customs of all kinds.

Like the Gloss, one Protestant critique would have it that these things “come between” the believer and the simple principles of the Faith, and limit the ways an individual can respond to Scripture or the other fundamentals of the Faith. Again, it is sometimes objected that the existence of these extra things adds unnecessarily to what a person has to accept, in practice if not in theory, when he accepts the Catholic Faith. Again, it is said that these things are not inspired or infallible, so they can be wrong or lead one in the wrong direction.

How should Catholics reply to such objections?

The Protestant reformers of the sixteenth century made much of their destruction of Catholic culture. In England, they called the physical artefacts associated with the Faith, from rosaries and thuribles to vestments and books, “Popish trash”, and in the town of Burford, not far from where I live, they hanged two uncooperative priests from their own church’s’ steeples, in their vestments, with more “Popish trash” hanging from their bodies. The Protestant and proto-nationalist movement of the Netherlands had a fictionalized hero, the “Maid of Holland”, whose rejection of the ancient Faith was symbolized by her sweeping Catholic rubbish (and Spanish troops) out of her orderly house with a broom. It was all to be neat, sparsely furnished, and as clean as a pin. American Puritan and Mennonite communities became associated with a similar aesthetic, among many others.

I should emphasize that Protestantism is a complex phenomenon, and not all of it results in the austerity of a Shaker parlor. I should also say that the understated, stripped-down aesthetic some of these communities produced can be very successful from an aesthetic point of view, and is an important component of the understated “English style” exemplified by Beau Brummell, which formed the basis of the classic men’s fashions of the 19th and 20th centuries; I would certainly not wish to repudiate it in its entirety. Rather, I am making a historical point about the original ideological component to the contrast, which is very widely noticed, between typical Catholic cultures and typical Protestant ones.

The familiar conflict between the flamboyant crypto-Catholic seventeenth-century Cavalier and the black-dressed Puritan is simplistic, almost to the point of falsity, and conceals a vast amount of complexity, but all the same there is something in it.

Furthermore, the ideological aspect of the contrast is still alive, lying at the heart of many arguments between Catholics and Protestants, arguments within the Catholic Church, and arguments among Protestants themselves, although it is often not very clearly recognized or articulated as such. The discomfort people of Protestant culture sometimes have with those videos of Spanish Holy Week processions that appear online, or traditional depictions of martyrdoms, or fine liturgical music, is deeply felt, and it has put many Protestants off from converting to the Catholic Church. Many other people of Protestant heritage have been enchanted by Catholic culture, and found it a pathway into the Faith.

But the value of culture shouldn’t be judged by its effect on outsiders. Having briefly expressed some objections to this culture, I want to respond by saying what it is actually for: what it adds to the bare bones of the Faith — and indeed, why the contrast between bare bones and something extra and less important is itself misleading.

The components of Catholic culture I listed earlier — various art forms, devotions, dress, festivals and customs — were not centrally planned, and vary a great deal between different places and over time. Nevertheless, they have an important function in the Catholic community, and the institutional Church has always been conscious of their positive role and fostered them, as well as guarding (as best it can) against anything bad that might arise in this context.

We can consider their role in several different ways. First, I will look at them in comparison with the cultural artefacts of other communities, in the context of the question of what might be bad about bad cultural practices (the ones the Church has to step in to discourage). Then I will return to the parallel with commentaries on the Bible.

The function of culture

What, then, is the function of culture in any society? It certainly makes life more interesting if there are games and dancing and nice clothes and food, but people’s attachment to their own culture suggests that its importance is not simply that of a recreation. Indeed, people make sacrifices to preserve and pass on their culture, and are often praised for doing so. National and international institutions exist to preserve culture: we all recognize that it has value.

In the 1964 film “The Train,” the French Resistance manage to prevent the Nazis from absconding with a trainful of priceless French paintings, just as the Allies were advancing on Paris. It is based on a true story, and the Resistance fighters paid a high price for their success. They were prepared to die, to kill, and to watch helplessly as hostages were machine-gunned, to keep these masterpieces of French art on French soil. They did not see these paintings as a mere form of entertainment, but as part of the soul of France. Their loss would have been a massive blow to French self-respect, because they were emblematic of French national identity. Such things are of no small significance to a nation struggling to come to terms with defeat and occupation. It was of great importance that the French had something to rally around, something that all Frenchmen could give allegiance to — even those, the great majority, who had never been to a museum to see these particular paintings.

All communities need markers of identity. This is only a small part of what I want to say about culture, but it is enough to establish the point that it is not an optional extra for a community: it is not something that is added to the business of eating and sleeping when a community is safe and prosperous. Culture is something a community needs even more urgently when it is fighting for its life, and it is indeed in moments of crisis that national heroes, shared experiences, and places and events of historic significance come into existence and then form the basis of a national culture, perhaps for centuries to come. Culture is not a luxury, but a necessity.

It makes sense, of course, for a community to rally around something that has real value. The French paintings were recognized as masterpieces by all sides of the conflict. They also exemplified and promoted specific values. These values can be difficult to articulate in some cases, and it shouldn’t surprise us that great works of art cannot always be turned into a set of verbal propositions. In other cases, however, at least some of the values are very easy to identify, and include religious and moral values, national pride, an appreciation of natural beauty, the achievements of people in the past, and so on. Art is the articulation of the values of a community and of the artist.

For both these reasons, it behooves the Catholic community to have a culture of its own. Although our community may overlap with other communities and allegiances, it remains a community in its own right, with its own markers of identity and values. Culture picks out or creates markers of identity, and articulates values.

In that case, we might ask, what could be bad about a cultural artefact? The answer is that there are some thoroughly bad traditions and practices, which reflect and articulate thoroughly bad ideas and principles, such as those of the mafia. It is important to recognize that a bad culture may still be necessary to the coherence of a community, that is to say, the members’ sense of common purpose and mutual trust and respect, if that is the only thing members of the community have in common. In the same way, a certain friendship might be glued together by a shared vice.

The collapse of a community as a community often brings in very serious problems, especially if we are dealing with a dominant or national community, and not just a sub-culture embedded in a larger culture. This means that the best way to deal with a thoroughly bad culture — one characterized by harmful, unjust, and exploitative practices — may be to try to reform the culture, rather than simply to suppress it. Even a good culture can go wrong, however, and it is the job of a culture’s gatekeepers, the people with cultural influence, to stop their culture being decisively influenced by really bad ideas before they take hold.

The Church’s magisterium has the charism of discerning true doctrine and error, and over the centuries it has suppressed expressions of popular piety which are not in accordance with the teaching of the Church. This is not always an easy task, as the long struggle over the popular but antisemitic cult of the young murder victim William of Norwich, and his imitators Hugh of Lincoln and Simon of Trent, in the course of the Middle Ages, demonstrates. In other cases it can be a matter of very fine judgements, as the story of liturgical music over the last five centuries illustrates. Finally, the Church has often permitted what is not obviously bad, rather than suppress what might well be harmful: an example of this is the toleration of artistic and devotional sentimentalism in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

I am not going to explore these issues further here. It suffices to say that culture is not an optional extra, but is essential to the functioning of a community, and that it expresses values, ideas, and principles, which can be bad as well as good.

Culture and commentary

Culture does not simply reflect principles that already exist in a community for other reasons. I said above that it articulates values, but it can do more than this: it can interpret, develop and create them.

A good Scriptural commentary is not supposed to add to the meaning of the text, but, since Scripture is an inexhaustible source of wisdom, a commentator (or preacher, or reader) can legitimately draw many different things out of it. Thus, commentary or meditation on a text is a matter not only of clarifying its meaning, but of drawing attention to certain aspects of it, as something of particular interest in the moment, or to a particular community. The same thing happens when a text is set to music or when its subject is depicted in religious art. The same thing again happens in the Rosary and the Stations of the Cross, when certain episodes become the focus of attention, and other things in the Biblical narrative are left in the background.

In this way, a particular religious culture will be characterized by the foregrounding of some things at the expense of others — not everything can be given prominence, after all. A particular school of spirituality, or the charism of a particular religious order, or the Catholic Church as a whole, can be described in these terms, and what is or should be given the most prominence can be debated and can change over time. Thus, in the second half of the twentieth century there was a debate in the Church about the traditional stress on Christ’s Passion in Catholic spirituality, as well as in theology and the liturgy. A Catholic brought up in a culture in which the Passion did have great prominence will have different devotional practices, and a somewhat different devotional attitude, in comparison to one whose devotional culture has its center elsewhere. He will see other aspects of the Faith in terms of their relationship with the Passion, and not the other way round.

Thinking in these terms, it is clear that even the lowest Protestant, even the advocate of nuda scriptura, has a specific religious culture, in the sense that his reading of the Bible is not random but shaped around certain key texts, and indeed key texts understood in very particular ways. The origin and development of this culture can be traced historically: the Protestant of today is the heir, whether he likes it or not, of centuries of critical debate interacting with religious practice. Then again, he inherits traditions of hymn-singing, of preaching styles, and even of architecture and religious art, as well social practices concerned with marriage, raising children, and many other things. Indeed, the project of freeing oneself from culture is itself the keynote of a culture of its own.

There is an element of this throughout Western culture. There is a widespread idea, for example, that artists or thinkers should prove their worth by revolutionizing their fields, and so reject the ideas of their immediate predecessors. Advocates of this idea often support their case by citing historical examples of supposedly revolutionary cultural figures. Look, they say: people have done this many times over the centuries, it is the characteristic feature of Western culture!

In other words, anti-traditionalism is the tradition, and rejecting the teachers of the past generation is actually following their example. There is a lot that could be said about this if we descended to specific examples, but it is sufficient to point out that for many people in art schools, for example, “being revolutionary” is actually the easy option, the one that requires no serious thought or creativity, just going with the flow of what is being taught and what is being done by everyone else. It has long ceased to be revolutionary to be “revolutionary”.

The ideology of anti-traditionalism is still different from the traditionalism associated with Catholic culture, however. The tropical growth of culture in Catholic societies depends on not even pretending to be revolutionary, but on building upon what others have done, with respect and love for the achievements of past generations.

This makes possible what is truly a multi-generational project: the development of a community’s self-understanding, and theological and devotional depth, over a period of time far longer than the working life of a single person, however talented he might be. This contributes to the Faith something much more than mere decoration: it constitutes an interpretation, a specification, and a making concrete in the circumstances of a particular time and place. It also makes it possible to pass it on to new generations and converts, not as a text or a set of propositions, but as a way of life.

In the Catholic Church, we have seen in the last sixty years an attempt by some to replace a traditional conception of our shared religious culture with a revolutionary one. It is common today to hear a critique of this attempt — that the baby was thrown out with the bathwater, despite the insistence of the revolutionaries that the fundamentals of the Faith were preserved.

The critique is correct, because even if the fundamentals, like Scripture and the theological principles of the Catechism, were preserved (and that was seldom the case on the ground), they are not self-interpreting, nor are they automatically absorbed into daily life. This is the role of authentic Catholic culture: even though it varies from place to place and over time, it is this culture which enables us to understand the fundamentals, and to live them.

OnePeterFive is making great efforts to restore our lost Catholic culture, as seen in today’s post about forgotten customs surrounding our Blessed Mother’s birthday.