For Arvo Pärt’s 90th Birthday: Gregorian Chant at the Origins of Tintinnabuli

I encourage those who are receiving this post in their email, or seeing it online, to consider listening to the voiceover. Not only do I read the article, I also incorporate all the musical examples. —PAK

As I was listening to J. S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations performed by Murray Perahia and the waves of exquisite intricate sound washed over me, a music altogether perfect in architecture and luminous with inevitability, and yet so spontaneous, energetic, and living that it seemed to have been a friend’s sudden utterance given solely for my joy, I could not help thinking: “The music of Bach is the absolute art, the eternal harmony against which all music is judged, before, after, forever.”

And then I began musing on how Arvo Pärt — who, born on September 11, 1935, celebrates today his ninetieth birthday — when he was thoroughly disillusioned with the empty promises of modernism and yet knew not where to turn, gravitated towards Bach’s music for his collage works, quoting some of the most euphonious and poignant passages as a longing glimpse of paradise lost, an invocation of healing beauty, a sacrament of meaning that would, if it could, effect what it signifies. And when, seven years later, Pärt emerged from a self-imposed retreat during which he immersed himself in chant and polyphony, his remarkable invention of the “tintinnabuli” style carried with it much of the earnest objectivity, necessity, and rational order of Bach’s music, as well as its unending surprises, acute (though highly spiritualized) emotion, and melodiousness welling up from the depths.

There are no “tunes” in Pärt; there are only stories of profound grief and joy, told in a patient conversation of contrasting voices whose pitches and rhythms seem to originate in and drive towards the transcendent good.

The use of the sustain pedal in Arvo Pärt’s 1976 piece “Für Alina” enables the tones to resonate and blend in such a way that there is a ghostly chorus in the background, singing (but ever so faintly) with the mighty chords of Passio or any of Pärt’s other great choral works.

The active “foreground” of the work is the two lines of the tintinnabuli — the essence of simplicity, with their transparent clarity and the consoling logic of their interaction — but the passive “backdrop” is the shimmering cosmos of harmonies and overtones that endure within the frame of the piano and make a slight work unexpectedly cosmic in scope. It is a solo miniature that is also a world of many voices. The subtlety of this musical effect is quite as amazing in its own right as any of the more overt exhibitions of the immense fecundity of the tintinnabuli style, like the Berliner Messe:

The reader is perhaps not surprised to hear at this point that Pärt is my favorite modern composer. I have nearly every recording and score of his music, have been blessed to be present at several concerts where the composer was present (including the premiere of In Principio in Graz), and, fifteen years ago, dedicated a set of seven choral compositions to him in honor of his seventy-fifth birthday, in thanks for which he telephoned me from Estonia (I will say more about that conversation below, in the appendix).

What I find so powerful about his music is that it breathes the spirit of ancient religious chant and yet the overall idiom, particularly the harmonic language, is thoroughly modern.1 It is obvious that the composer deeply loves and believes in the realities with which he is dealing, and, as a result, treats every word, every phrase, with an intensely sympathetic and sensitive care. This is no less true of his purely instrumental works such as the Fourth Symphony.

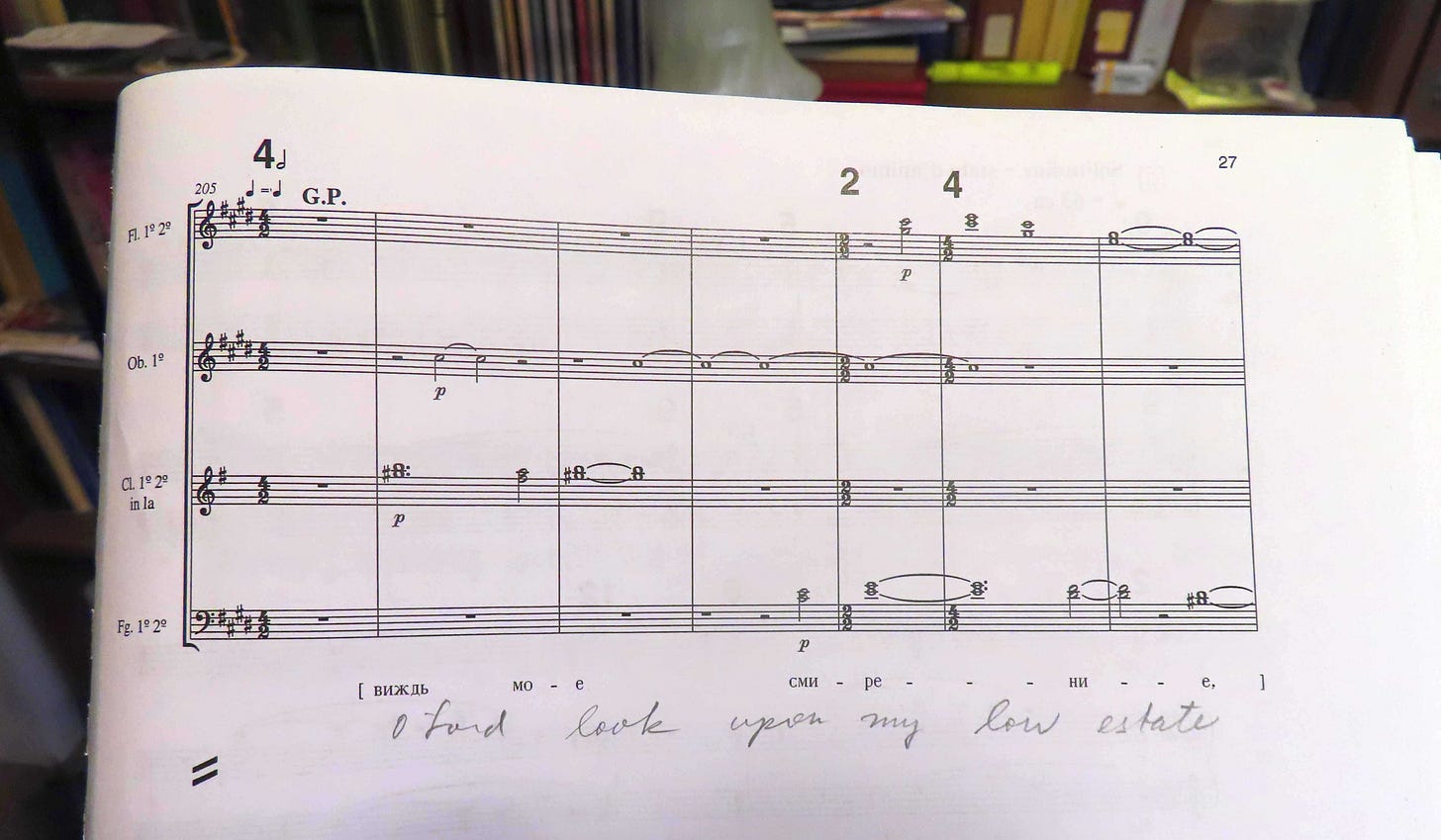

Often in his orchestral scores one sees a Slavonic liturgical text implanted in the instrumental parts, as if the violins are a choir wordlessly singing to the Lord — a striking reinterpretation of the idea of a “string choir.”

In an interview in 1978, not long after Pärt’s first tintinnabuli pieces, Ivalo Randalu asked him: “Let’s take, for example, ‘Tintinnabuli’. What do you try to discover or find or achieve there? That keynote and the triad; what are you looking for there?” To which Pärt responded:

Infinity and chastity. … I can’t explain, you have to know it, you have to feel it. You have to search for it, you have to discover it. You have to discover everything, not only the way to express it, you have to have the need for it. You have to desire it, you have to desire to be like this. All the rest comes itself. Then you’ll get ears to hear it and eyes to see it.

One could say many things about the special qualities of Pärt’s music, but the purpose of this article is rather to let the composer himself speak about a certain discovery that he considers decisive in his career, his discovery of Gregorian chant, and how that profoundly affected his entire artistic development. It is inspiring to hear this composer, considered one of our greatest living artists, speak about the greatest collection of melodies in the history of music.

In a 1988 interview with Martin Elste, Pärt says:

Gregorian chant has taught me what a cosmic secret is hidden in the art of combining two, three notes. That’s something twelve-tone composers have not known at all. The sterile democracy between the notes has killed in us every living feeling.2

From a conversation in 1990 with Roman Brotbeck and Roland Wächtner:

Gregorian chant was for me the first impulse [toward a new beginning]. It was unadulterated admiration. I had never heard this music before. And when I came across it by chance, I knew: this is what we now need, what I now need.3

In December 2000, Jordi Savall had a conversation with Pärt that first appeared in French in 2001. Here is how the composer describes his transformative encounter with chant:

In the beginning, during my twelve-tone period, I lived truly separated from original sources. And the turn I took, it was a matter of learning how to walk all over again. Undoubtedly, the reason such a metamorphosis takes place in certain people and not in others will forever remain a riddle; all I know is that when I heard Gregorian chant for the first time, I must have been mature enough, in one way or another, to be able to appreciate such musical richness. At that moment I felt at once utterly deprived and rich. Utterly naked, too. I felt like the prodigal son returning to his father’s home. I had nothing, I had accomplished nothing. The methods I had used before had not allowed me to say what I wanted to say with music, yet I did not know any others. At that moment, my previous work seemed like an attempt to carry water in a sieve. I was absolutely certain: everything I had done until then I would never do again. For several years I had made various attempts to compose using collage techniques, mainly with the music of Bach. But all of that was more a sort of compromise than something I carried in my flesh. Then this encounter with Gregorian music… I had to start again from scratch. It took me seven, eight years before I felt the least bit of confidence — a period during which I listened to and studied a lot of early music, of course.

Simply put, at that time [around 1970], I had already distanced myself from all those [political] movements and struggles for freedom. I believe that anyone who wants to change the world must begin not at the other end of the world, but that the starting point must be within him. And this is accomplished millimeter by millimeter.

Ideally I would be able to write a melody with an infinite voice, that carries on forever. Music that would be like speech, like a flood of thought. … In music, one could say that a voice or a melodic line is like a man’s soul. In this sense, polyphony would have more to do with the idea of a crowd. The richness of the music of many voices is, however, the sum of the wealth of each of these melodic lines — as was the case in the polyphony of the great masters of the past.4

Here is Pärt’s setting of the text “Da pacem, Domine” (from the album In Principio):

Enzo Restagno held a lengthy conversation with Pärt in July 2003, in which the maestro said:

In order to go on [after a crisis] one has to break through the wall. For me, this happened through the conjunction of several, often accidental, encounters. One of these, which in retrospect turned out to be of great importance, was with a short piece from the Gregorian repertoire that I heard quite by chance for a few seconds in a record shop. In it I discovered a world that I didn’t know, a world without harmony, without metre, without timbre, without instrumentation, without anything. At this moment it became clear to me which direction I had to follow, and a long journey began in my unconscious mind. …

It wasn’t until later that I realised one can express more with a single melodic line than with many. At that time, given the condition in which I found myself, I was unable to write a melodic line without numbers; but the numbers of serial music were dead for me as well. With Gregorian chant that was not the case. Its lines had a soul….

At the time [the years just after Credo of 1968] I was convinced that I just could not go on with the compositional means at my disposal. There simply wasn’t enough material to go on with, so I just stopped composing altogether. I wanted to find something that was alive and simple and not destructive. … What I wanted was only a simple musical line that lived and breathed inwardly, like those in the chants of distant epochs, or such as still exist today in folk music: an absolute melody, a naked voice which is the source of everything else. I wanted to learn how to shape a melody, but I had no idea how to do it.

All that I had to go on was a book of Gregorian chant, a Liber usualis, that I had received from a church in Tallinn. When I began to sing and to play these melodies I had the feeling that I was being given a blood transfusion. It was terribly strenuous work because it was not simply a matter of absorbing information. I had to be able to understand this music down to its very roots: how it had come into existence, what the people were like who had sung it, what they’d felt during their lives, how they’d written this music down and passed it on through the centuries until it became the source of our own music. … I had succeeded in building a bridge within myself between yesterday and today — a yesterday that was several centuries old — and this encouraged me to go on exploring. During those years I filled thousands of pages with exercises in which I wrote out single voiced melodies.5

Pärt can help all of us to perceive once more, as with fresh ears, the tremendous, inexhaustible goodness and fertility of Gregorian chant.

Although little of his music is based directly on chant motifs (the way that, for example, Bach’s Credo of the Mass in B minor, Liszt’s Totentanz, or Duruflé’s Requiem are), nearly all of his works are permeated with a chantlike feel and spirit. Listen to the shaping of the melodic lines in the Te Deum:

And in the Passio Domini Nostri Jesu Christi Secundum Joannem:

You can perceive the influence of Gregorian chant’s fluidity of phrasing, where the musical rhythm cleaves to the exigencies of the word; its modal character and subtle emotion, which resist the superficiality of major-happy and minor-sad, tending rather towards a stance of contemplation. Both chant and tintinnabuli seem to be well described by Plato’s definition of time as a “moving image of eternity.”

For Pärt, as his compositions and conversations reveal, music is an elemental mystery that must be approached reverently and silently. Paradoxically, music can spring up only in silence, it originates and resonates only in silence, and the appreciator, no less than the composer, must have a quiet soul. Even when agitated, his soul must, in a deeper way, be still, that is, receptive to the influence of the muses, or grace. Grace accounts for man-made beauty; wherever there is beauty in man’s works, grace is operating. Whether it be supernatural grace or the gift of the powers latent in human nature, God speaks through the arts in their highest manifestations, so much so that the arts may be considered a nest for the Gospels, a translator of the obscure tones of mystery into the bright tones of human feeling and knowing, a fellow laborer of scientia in the work of preaching Christ.

My experience with a lot of contemporary “art music” (obviously, I make room for exceptions) has been that it sounds more interesting when described than when listened to. I have a theory about why this is so. Music, of course, is notoriously hard to describe in words. The more beautiful it is as music, the more it escapes definition; how can one really describe the music of Bach or Mozart, except in a rather technical and almost clichéd way (“this movement is in modified sonata form, with a sprightly first theme followed by an impassioned, darker theme in the relative minor…”)?

In the twentieth century, however (and to the present), many composers allowed themselves to be dominated by a mentality borrowed from the novel and the cinema: they want their music to be about something — war or peace, refugees, AIDS, climate change, social justice, or whatever cause du jour may animate them. They then use musical resources in a poetic or novelistic or cinematographic manner, i.e., not precisely in the way proper to music. As a result, one can talk quite volubly and excitedly about the music, about what it “represents” or “advocates” — but when you listen to it, it fails to impress as music.

In short, there is a language proper to music, and it is a highly abstract one that depends on a keen feeling for “beautiful sound.” Someone like Arvo Pärt has rediscovered this. If one tries to describe Pärt’s style, one finds oneself resorting to abstractions. The same is true for Bach.

I think in the end one must adopt a stance of humility before the mystery of music. Pärt himself has said:

The complex and many-faceted only confuses me, and I must search for unity. What is it, this one thing, and how do I find my way to it? Traces of this perfect thing appear in many guises — and everything that is unimportant falls away. . . . I have discovered that it is enough when a single note is beautifully played. This one note, or a silent beat, or a moment of silence, comfort me. I work with very few elements — with one voice, with two voices. I build with the most primitive materials — with the triad, with one specific tonality. The three notes of a triad are like bells. And that is why I called it tintinnabulation.6

His music bears witness to the primacy of simple givens — including silence.

The qualities of beautiful music

Our experience of beauty is necessarily subjective, but the qualities that make a work of art beautiful are inherent to it and thus objective. This interplay between subjective perception and objective qualities is the reason why we can have different tastes while nevertheless most educated or cultured people tend to agree on who the great artists are and why their works are wonderful.

St. Thomas talks about integrity, proportion, and clarity as the three marks of the beautiful, and there’s much to commend that view, although it needs to be considerably fleshed out when applied to music. One might consider connecting that triad with the one given by Saint Pius X, who says that sacred music should have the qualities of holiness, sound artistic form, and universality.

It seems to me that the property of holiness might correspond to clarity or glory, the property of sound form to proportion, and the property of universality to integrity. When the whole work is as it should be and what it should be for its purpose, it is universally appreciated; when its component elements — voices, instruments, lyrics, counterpoint, homophony, texture, timbre — are well ordered from and toward the whole, it manifests its provenance in reason as a sound construction; when the finished work radiates with a glory that exceeds the sum total of its parts, that transcends this mutable world and bears witness to what is eternal, it glorifies God and begets some likeness of Him in the soul.

These three marks of St. Thomas and three qualities of St. Pius X, however one might choose to correlate them, are found to a superlative degree in the music of Arvo Pärt.

Thus, I cannot but differ with the bizarre critique, offered by no less a figure than James MacMillan (though not only by him), that Pärt’s music is too static, serene, and undramatic to be music that reflects this world and the descent of Christ into it.7 I find this baffling. The sheer dissonance of Pärt’s music is highly dramatic (e.g., the Passio secundum Joannem). The texts he sets to music are of enormous spiritual depth and are often set with passionate gestures: think of the Berliner Messe; the O Antiphons; Litany of St. John Chrysostom; Adam’s Lament; the Te Deum (a work of shattering intensity). It’s almost as if the critics haven’t bothered to listen to much beyond “Für Alina”!

I would actually mount a contrary critique of many contemporary pieces: the degree of agitation and dissonance used at times reminds me not so much of the fallen world into which the Light has descended as of a hell into which the Light cannot descend. MacMillan’s own finest works, to my mind, are the ones that express “Light shining in darkness” — a description I would apply nearly across the board to Pärt’s compositions. After the 1970s, it only rarely happens that a work of Pärt’s exhibits, to my ear, an excess of asperity or aggressiveness. It seems that the “tranquility of order” he first discerned in Gregorian chant has somehow remained with him over all the decades of his creative career.

On the occasion of his ninetieth birthday, I give thanks to God for Arvo Pärt as a man of integrity, an Orthodox Christian, a composer of genius, and a witness to the beauty that never perishes. Mnohaya lita! Ad multos annos!

Appendix: My Phonecall with Pärt

Here, I share for the first time the notes on my telephone conversation with Arvo Pärt that took place on October 29, 2010.

Upon receiving from his agent in Vienna (Universal Edition) the seven-part composition that I had dedicated to him, he had telephoned my office number, which was written on the cover letter. At the time, I was in class, teaching. When I got back to my office, I saw the message light blinking, and this is what I heard:

I could hardly believe my ears. My heart was racing. I looked at the phone number in my “missed calls” and decided to try it. Arvo Pärt picked up the phone. Here is what I wrote after our short conversation.

I can’t remember the exact order of the elements of our 12½ minute conversation, but I’m pretty sure I’ve got them all written down, even if the order isn’t the same.

Pärt was delightfully conversational, easy to talk to, a true gentleman; he made me feel that he was sincerely interested in talking to me, not rushed or inconvenienced. The notable limits of my German were, of course, the limits of our conversation, and that made it difficult to say anything more than simple sentiments; but nevertheless it went well enough, given that he and I were not at all acquainted with each other.

I dialed the Estonian number, and Pärt answered the phone, but not sure that it was he, I asked (auf deutsch, natürlich) to speak with him; he was pleased to hear from me and to find out that I spoke some German. He reiterated his positive remarks about the Antiphons, saying they were true liturgical music, appropriate for church use, and commented that although there is a lot of music being written today, too little of it is for the church. He used the word “polyphony” again, in an approving way.

He said: “I was honored to be the recipient of these pieces” — a rather amazing statement that I will have to accept on faith! I commented that I noticed he was with the Holy Father earlier in October; he said, “Yes, he was at my concert — I mean, I was at his concert!” I said: “Ich liebe dieses Oratorium Cecilia, vergine romana.”

He then asked me where I am working and what my position is; I told him that I am a professor of theology “at a university” and that I direct a choir and write music “for the love of it” (this part would have been easier if I could have spoken better German). He asked “college or university?” and I said “a college.” He wanted to know where, guessing California, and I told him “Wyoming, in the middle of the States; not too far from Denver, Colorado,” which I knew Pärt would have heard of.

He asked me where I got my musical training and I told him that I had studied with an organist; he then commented that he had met many fine organists in Germany who were capable composers as well. I said this only makes sense, as an organist has to know how to improvise, but my remarks at this point were in English and I’m not quite sure he followed. I told him at some point in the conversation that I am Roman Catholic and that I write “Gebrauchsmusik für die Liturgie.”

He asked: “Oh yes, how old are you?” I said: “Almost 40.” He replied: “Ah, that is very young. If I live for five more years, I’ll be 80!” I said: “And I wish you a belated happy birthday!” He asked: “Are you Polish then? With the name Kwasniewski…” I said: “Yes, but I do not speak Polish; my father could speak some.” He said: “Then you were born in America” and I assented. He commented: “You do speak quite a bit of German.” I said that I lived for seven and a half years in Austria, that I was a teacher at an English-speaking school between Vienna and Salzburg.

He asked, if I understood him aright, whether there was a conductor who would lead a performance of the Antiphons. I tried to say that I wasn’t acquainted with a conductor at this time but I’m afraid what I said was: “I don’t know a conductor who could direct this music” (!), and that my choir, being amateur, could do Palestrina and Bruckner, but not the Antiphons (!). His reply was: “No, no, the music is sehr logisch geschrieben,” that is, the parts make sense, and so should be accessible to amateurs. He then observed: “One can, of course, also write more simply.”

He mentioned, as if it had just occurred to him because speaking with an American, that an article about him had recently appeared in the New York Times and that its author had spent some time with him; he seemed somewhat amused. I told him: “Ja, ich habe das gelesen.” We then thanked each other again (I said pointedly: “Thank you for your music” — would that I knew how to say more!), and he said: “I wish you all the best, and God’s blessings.” I said (foolishly, I don’t know): “Auf wiederhören” — until we speak again!

What a blessing and a privilege it was to speak to this eminent composer, this cultured gentleman, this spiritual beacon. May the Lord reward him for his kindness and his Christian artistry.

Here are a couple of the movements of my “Seven Mandatum Antiphons”:

To see and hear more of my compositions, visit my music website “Cantabo Domino.”

Coda

A bonus recording, for those who’ve read this far:

The enormous difficulty of performing Pärt’s music forces a “co-creation” between composer, musicians, and recording engineer that flies in the face of the Romantic exaltation of the creative genius and of the live moment. This is one among many ways in which Pärt is distinctively modern, neither medieval (in spite of his medieval sources of inspiration) nor Romantic.

“An interview with Arvo Pärt,” Fanfare 11 (March/April 1988).

Arvo Pärt in Conversation (Champaign, Illinois: Dalkey Archive Press, 2012).

The English translation was printed in Music & Literature 1 in 2012.

Arvo Pärt in Conversation, 18; 28–29.

Quoted by Wolfgang Sandner, in the liner notes of Tabula Rasa, ECM 1275.

See Carmen-Helena Téllez, “Arvo Pärt: The Unexpected Profile of a Musical Revolutionary.”

Thank you for something positive on what I experience every year as the saddest anniversary in American history. I am only a little familiar with Part's music. It reminds me of Terrence Malick's sonic sensibility in his films, and indeed Malick used Part in three of his movies, including "A Hidden Life" about Bl. Franz Jagerstatter. Part has such an interesting background, esp. being a non-Slavic Orthodox in a region dominated by Russia (and formerly the Soviet Union). Imagine an Orthodox Estonian discovering the music of the Latin West in an area once fought over by the Teutonic Knights. And Bach? He is the Master, always making music that glorifies God.

The selections from the Dona Nobis Pacem and In Principio were stunning. Very compelling music. The latter reminded me of Poulenc’s Gloria. Thank you, Dr. K.!