Interview with Dr. Kwasniewski on Music: The Good, the Bad, and the Holy

The music we make or listen to has serious moral and spiritual implications

Natalie Sonnen of Regina Magazine asked if I would answer some of her questions on music. This fall, a version of the interview will appear in the pages of that magazine, but with permission, I am sharing the text here at my Substack ahead of time.

Natalie: Isn’t the music we listen to a matter of indifference? Surely, it’s just superficial entertainment.

Dr. Kwasniewski: Such may be a common point of view in the modern democratic Western world, but it is a minority opinion in the history of human thought—and I’m not quite sure that anyone really believes it anyway.

That music has a profound effect on the formation and development of our human potentialities and moral character is the teaching of Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Pieper, Ratzinger, and Scruton, among other heavyweights—and surely, when thinkers who disagree about so many other things agree on this point, their agreement should give us pause.

If what these thinkers hold is true, music cannot but affect our lives as Christians and our eternal destiny. According to the two greatest philosophers of antiquity, Plato and Aristotle, whenever we listen to music, we are allowing it to come inside and make its home in our souls. We are saying: Shape me; make me like yourself. We wouldn’t sleep with just anyone, or entrust our education (or that of our offspring) to just any teacher—yet we often allow sordid characters and their cheap goods to enter the doors and windows of our body and live inside our minds and hearts! Plato in particular argues that what we really believe, what we are, is most of all revealed by that in which we take pleasure.

If our tastes in music or movies are the same as those of modern American atheistic hedonists, what does that say about the strength of our faith or the vitality of our intellectual life?

Exactly. The Logos, the Word of God, should permeate our thinking, our feeling, our loves and hates, our way of being human. This is what it means to live a life of virtue and to be a son of God. We become beacons of light, keeping alive the memory of the beautiful and attracting others to a nobler way of thinking, living, being.

That we are supposed to care very much about the reformation of our interior life, especially by turning away from corrupt passions, is impressed on us by Saint Peter:

His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness, through the knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and excellence, by which he has granted to us his precious and very great promises, that through these you may escape from the corruption that is in the world because of passion, and become partakers of the divine nature. (2 Pt 1:3–4)

So far, so good. But all of the above is too general—painting with a broad brush. Can you be more specific about what’s wrong with the music you once told us you threw away in high school, and what, in contrast, is so good about the more artistically refined music?

Rhythm is the most basic element of music, the most primitive. This is why the music of some primitive cultures consists mostly of drumming. More advanced cultures, presupposing the framework of rhythm, develop beautiful melodies above it. The most advanced, presupposing both rhythm and melody, develop a system of harmony. When you listen to a piece by (e.g.) Palestrina, Bach, Mozart, Tchaikovsky, or Arvo Pärt, the rhythm, although discernible, is subordinated to the melody and harmony, which take “center stage.”

Pop, rock, rap, metal, and other such “popular” styles are unhealthy for the soul because they invert this rational hierarchy of rhythm, melody, and harmony. They accentuate the beat, strip the harmonic framework to a bare minimum, and employ repetitious, unlyrical “melodies” (if they can even be called that) in order to stimulate the concupiscible and irascible sense-appetites in a disordered manner, stoking anger or lust (and sometimes both). We are dealing here with music deliberately primitive and passionate, simplistic and sensual.

It is one thing for such music to proceed from genuine savages who know no better, but it is quite another for it to proceed from the descendants of a rich folk culture and a resplendent high culture. In the latter case, it is a rejection of their own inheritance, a symbolic statement of repudiation and revolution. We may compare it to the difference between naïve pagans who do not yet know the Gospel and nihilistic neo-pagans who hold it in contempt—so much so that they do not even bother to find out whether or not they understand what they are rejecting.

You are saying that the rhythm of the music has a lot to do with its moral influence, and with the evaluation we should make of it?

That’s right. We can see the simplism and sensualism of many “popular” forms of music if we look at the rhythmic underpinning.

All traditional Western musical styles follow the principle of the downbeat, where the first beat in a measure of 3 or 4 beats is the most accentuated, as is quite natural. Syncopation—the practice of accentuating an “off ” beat—is used by great composers as “spice,” but pop styles lean on it relentlessly, monotonously, to induce a kind of false ecstasy. Rock music in particular is defined by the continual accentuation of the weak beats (2 and 4) rather than the downbeat and its partner (1 and 3). This accentuation is unnatural: it is the MSG of the music world.

The rarity of triple time (3/4, 6/8) in pop culture is also indicative: it bespeaks a loss of the art of dance. Dances in triple time are notable for their lilting, gentle, noble, or debonair attitude. In the pulsating, gyrating, pumping, aerobic-type exercise that many nowadays call “dancing,” such tripletime dances of the past, which were numerous, widespread, and beautiful, are gone. If ever there was a manifest sign of cultural degeneration, it would have to be the descent from minuet to waltz to swing to disco to deafening nightclub mixes of throbbing monotony. With each step in the descent, we see a lessening of the social and communal dimension of dance, which is supposed to be an imitation of the orderly cosmos and the relations of the sexes within it; with each step, we see a decrease of formal beauty, a lapse of dignity, a loosening of morals, a growing contempt for order, symmetry, coordination of partners.

Would you say, then, that listening to music bad for your soul is actually sinful?

With much of the bad music out there, we are not dealing with something intrinsically evil, as if the mere listening to it would constitute a mortal sin. Rather, we are dealing with something relatively evil: something that indicates and fosters moral imperfection, which, if unresisted, may lead to mortal sin.

Saint Thomas Aquinas argues that venial sin is bad not only because of the offense in itself, light though it may be, but also because repeated venial sins are a slippery slope to mortal sin. By listening to rock or pop or rap, one is stunting one’s moral growth, depriving oneself of intellectual perfection, and impeding or clouding one’s spiritual life.

I would put it this way. Today’s popular music is largely unhealthy for its imbibers, in a way that is not dissimilar to the way in which eating junk food or doing drugs is bad for your body, playing videogames is bad for your psyche, or seeking sexual pleasure for its own sake or looking at pornography is bad for your soul. It can also be bad for you in the way in which reading only comic books when you could be reading great literature is bad, or dressing sloppily or immodestly when you could dress well. All these things are connected to the moral life and, ultimately, to the spiritual life.

Let’s shift gears and talk about the music we should hear in Church. Given what you’re saying, wouldn’t it be wrong for this music to be like secular music—let’s say, like pop, or rock, or folk? To be informed by the styles and techniques of music that comes from the world?

It would be utterly backwards to let the tastes of popular culture in its deviation into mass-marketed pseudo-art dictate what Catholics ought to esteem and rely upon. Since the Church’s liturgy is the Passover Feast, it has to bring us out of the world, out of Egypt. For this reason, it ought to have a certain “strangeness”; it should be a challenge to the comfortable categories by which we live in the secular world, surrounded by familiar idols. In the liturgy, we are trained to leave behind the mind of the world and put on the mind of Christ. This means that what is “unclean” to worldlings must be embraced by us—for example, silence and religious chant—and that what is “clean” for worldlings must be held by us as unworthy and profane, such as pop music and amplified blather.

Richard Terry describes the contrast as follows:

I think we may say that modern individualistic music, with its realism and emotionalism, may stir human feeling, but it can never create that atmosphere of serene spiritual ecstasy that the old music generates. It is a case of mysticism versus hysteria. Mysticism is a note of the Church: it is healthy and sane. Hysteria is of the world: it is morbid and feverish, and has no place in the Church. Individual emotions and feelings are dangerous guides, and the Church in her wisdom recognises this. Hence in the music which she gives us, the individual has to sink his personality, and become only one of the many who offer their corporate praise.

Just think about the implications of Terry’s remark—“Individual emotions and feelings are dangerous guides, and the Church in her wisdom recognises this”—for something like the Praise & Worship music used by charismatics!

But why was there such a huge emphasis after Vatican II on making new music in a “popular” style?

My experience is that many Catholics, especially of a certain generation, consider music in a purely utilitarian way: it’s just a means to some further end, usually “active participation” understood in a reductive sense. It has no intrinsic value; it is not a holy (or unholy) thing; it is not “a moving image of eternity.” It’s something you do in order to be doing “something religious as a group.”

This is why music, for them, doesn’t have to be of a high artistic quality. In fact, music of such quality would tend rather to thwart the end of “everyone doing everything” than to promote it. The implicit lesson of religious “utility music” (Gebrauchsmusik is the term used by Ratzinger) is that liturgy is a pragmatic self-service, a kind of churchy cafeteria, rather than a losing of oneself in something higher, greater, stranger, more demanding, and ultimately more wonderful than anything we can invent out of our immediate resources.

The irony, of course, is that sacro-pop cannot truthfully be said to have achieved that “We Are the World” level of cooperative singing that was its sole justification. Meanwhile, we have had to suffer battery and siege on our eardrums, while the Muses scurried away for cover. We can be consoled at least by the inevitable operation of a divinely revealed law: the fashion of this world is passing away, and all that is conformed to this world will also pass away.

Getting back to Richard Terry’s words, he’d say Gregorian chant has this character of health and sanity.

Quite so. It’s the oldest of the “old music” he praised. Tellingly, my high school summer students loved it when I played for them recordings of chant and polyphony. They’d say, “I’ve never heard such beautiful music before. If only my parish back home would have music like that!” Or, “It’s really hard for me to pray at my parish, because of the guitars and the clapping.”

The Catholic Church’s music is some of the most sublime and beautiful ever written by man, for the glory of God and the uplifting of souls. I can’t help thinking that the Catholic Church today is like a dining room lined with cabinets holding the most stunning plates, silverware, and glasses—and there we are, serving our meals on Styrofoam plates with plastic cutlery and paper cups. Perhaps the meal is the same, but what a difference it makes how the meal is served! People recognize far better the specialness of the banquet, the value of the food and drink, when it is served in beautiful vessels and with loving attention to how the service is executed.

The faithful by and large do not have a clue about the riches that belong to them—the riches that Vatican II said should be “fostered and preserved with great care.” Fortunately, those cabinets are still there, with their precious contents ready to be discovered anew.

So you’ve found that young people react very positively to things like Gregorian chant and old-school polyphony.

Yes. Many not only can respond to this music and art but, having been exposed a little to it, already love it or find it intriguing and convincing, or to use a favorite word, authentic. They love the sound of Latin and chant, the look of Gothic cathedrals, stained glass windows, noble statuary. Witness the ongoing popularity of recordings of medieval and Renaissance music, or the steady appearance of art books filled with photographs of the great churches, altarpieces, and tapestries of yore.

Such things are perennially appealing to everyone, from the illiterate to the highly educated. All you have to do is watch the looks of amazement and wonder on the faces of visitors to cathedrals in Europe. Majestic beauty still speaks powerfully of the divine, the eternal, the immortal, the spiritual. It is sensuous catechesis, experiential mystagogy. We human beings need it.

Tell us more about Gregorian chant in particular. Why is it special?

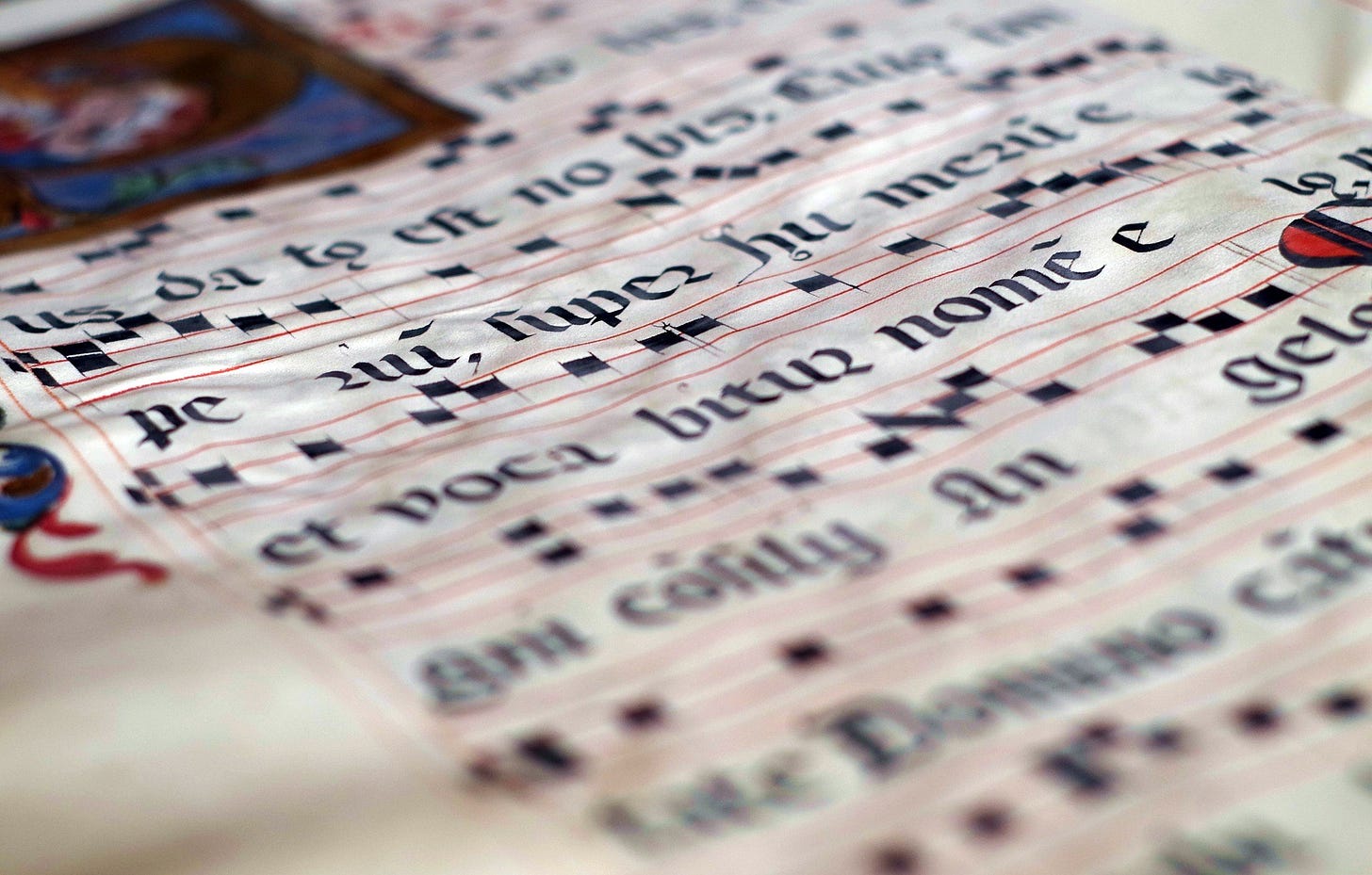

Chant is the music, custom-made, that grew up with the Church’s liturgy. It has eight qualities that make it utterly distinctive among musical forms: primacy of the word; free rhythm; unison singing; unaccompanied vocalization; modality; anonymity; emotional moderation; unambiguous sacrality.

Chant is, above all, music in service of God’s revealed word, to which it grants primacy. It is sung prayer: it exists to proclaim and interpret divine words or human poetry inspired by those divine words. Gregorian chant, the music native to the Roman rite, can be called “words with wings”—born of a deep savoring of the Word of God, in harmony with divine beauty, and capable of lifting the mind and heart to the threshold of eternity.

A very special feature of chant is how its musical phrases follow the natural rhythm of Scripture, which is not written in meter. Because chant is not confined to a predetermined grid of beats, such as duple or triple time (think: march or waltz) but conforms to the syllables of the words, its phrases seem to float, flow along, meander, and soar. It breathes rather than marches ahead; it moves with a wave-like undulation, or like birds circling in the sky. A large part of the special “aura” of chant is caused by its unconstrained fluidity and freedom of motion, which seems to break out of the hegemony of earthly time and the constraints of the flesh represented by the beat.

Because our ears are so habituated to the major/minor key system (and have been for centuries), Gregorian chants, which employ eight “modes” that seldom conform to our modern musical expectations, strike us as otherworldly, introspective, haunting, incomplete. It reminds us of the holiness and unchanging truth of God, His strangeness or otherness, His transcendent mystery, the special homage He deserves, and the need for our conversion from the flesh to the spirit—that is, from a worldly mentality to a godly one: “Be not conformed to this world; but be reformed in the newness of your mind” (Rom. 12:2).

So it’s a positive, not a negative, that chant has so little connection with our typical musical styles from modern times, that it’s so “foreign” in that sense…

Let me put it this way: chant is not entertainment music, or fill-in-the-gaps background music, or keeping-people-busy music. It is ritual music, embodying and actualizing and carrying forward the worship of God, and therefore counts as itself a sacrificial offering blessed by Him and bestowing blessings on those who fall into its waves.

After singing and listening to chant for many years, I find melodies and words coming back to me at odd hours of the day and night, reminding me of God and of my heavenly fatherland. This music puts down deep roots in the soul; when we hear it start up in church, the very sound of it calls us to prayerful attention.

You’ve criticized excessive emotionalism, or better, disordered emotions, in music. Does chant help us in this regard?

Absolutely. The emotions expressed in chant are moderate, gentle, noble, and refined. They induce and conduce to meditation. In this way, chant is well suited to the ascent of prayer. The “temperance” of chant takes on a special importance in our times, when so many people live a fast-paced (if not frantic) life, wearied from excessive stimulation—the constant input of music, movies, videos, the internet. Although chant has positively affected mankind for centuries as a summons to greater interiority, an aid for achieving restful silence, and a guardian of right spiritual hierarchy, for us moderns it carries additional value as a medicinal remedy, a health-giving purgative.

As Giacomo Baroffio says, “Liturgical prayer teaches us to put ourselves on a wavelength independent of worldly chaos… Gregorian chant has the power to sing, to divert the heart from preoccupations, because it orients itself to God in adoration and silence.” Human beings are created to contemplate God. Gregorian chant prepares us for this contemplation and inaugurates it. Chant evokes and draws us towards the beatific vision.

Do you think listening to and singing chant helps people relate more responsibly to music in general? That it purifies and elevates their standards?

I believe that sacred music—above all Gregorian chant, but also medieval and Renaissance polyphony, which are based on it—exhibits the essential characteristics of the art of music with particular luminosity and thereby helps us to understand music’s God-given role in life.

It seems to me that all the music we listen to should be compatible or harmonious with sacred music. This doesn’t mean that we should listen to sacred music all the time (that would be strange: it is appropriate sometimes to dance at a wedding banquet after the High Mass is done, and sacred music is meant for worship, not for running or chopping logs); rather, it means that our our spiritual and liturgical life should not be a sealed-off compartment that has nothing to do with our secular life. It means that our secular taste should not do battle against or dilute or undermine our spiritual needs as sons of God.

There should be a relatively smooth transition from work, recreation, and leisure outside the church to the prayer that goes on inside the church; from inside the church to the Blessed Sacrament; from the Blessed Sacrament to contemplation and the beatific vision. The Catholic view is that our whole lives are to be offered up as a pleasing sacrifice to God, in union with Christ, and on pilgrimage to heaven (see Rom 12:1; Phil 4:8; Col 3:3).

Coming across this excellent interview this morning was very providential, Dr. Kwasniewski, as I just posted a reflection on my blog on the importance of authentic sacred music (and the primacy of Gregorian Chant) in the Church's sacred liturgy. Thank you for another thoughtful interview on a crucially important topic relating to liturgical restoration. God bless you.

Zuckerkandl calls repeated syncopation “rhythmic dissonance” which I think is an insightful formulation.