Not Praying for Departed Souls: The Scandal of the Modern Catholic Funeral

Collapse in prayer for the dead is directly connected to the new rite of Mass

Once upon a time, a very important person in my life died. I attended the funeral. It was a Novus Ordo canonization ceremony, conducted by a priest and three women in skirt-suits ministering in the sanctuary. Everyone at the funeral was dressed in black—except for the priest, who was wearing white. The disjunct was glaring and tasteless. The contrast between the deep human instinct of mourning, which can be said to be an ineradicable part of the sensus fidelium, and the crackpot liturgical reformers who introduced white as a color for Masses for the dead, was never so obvious to me.

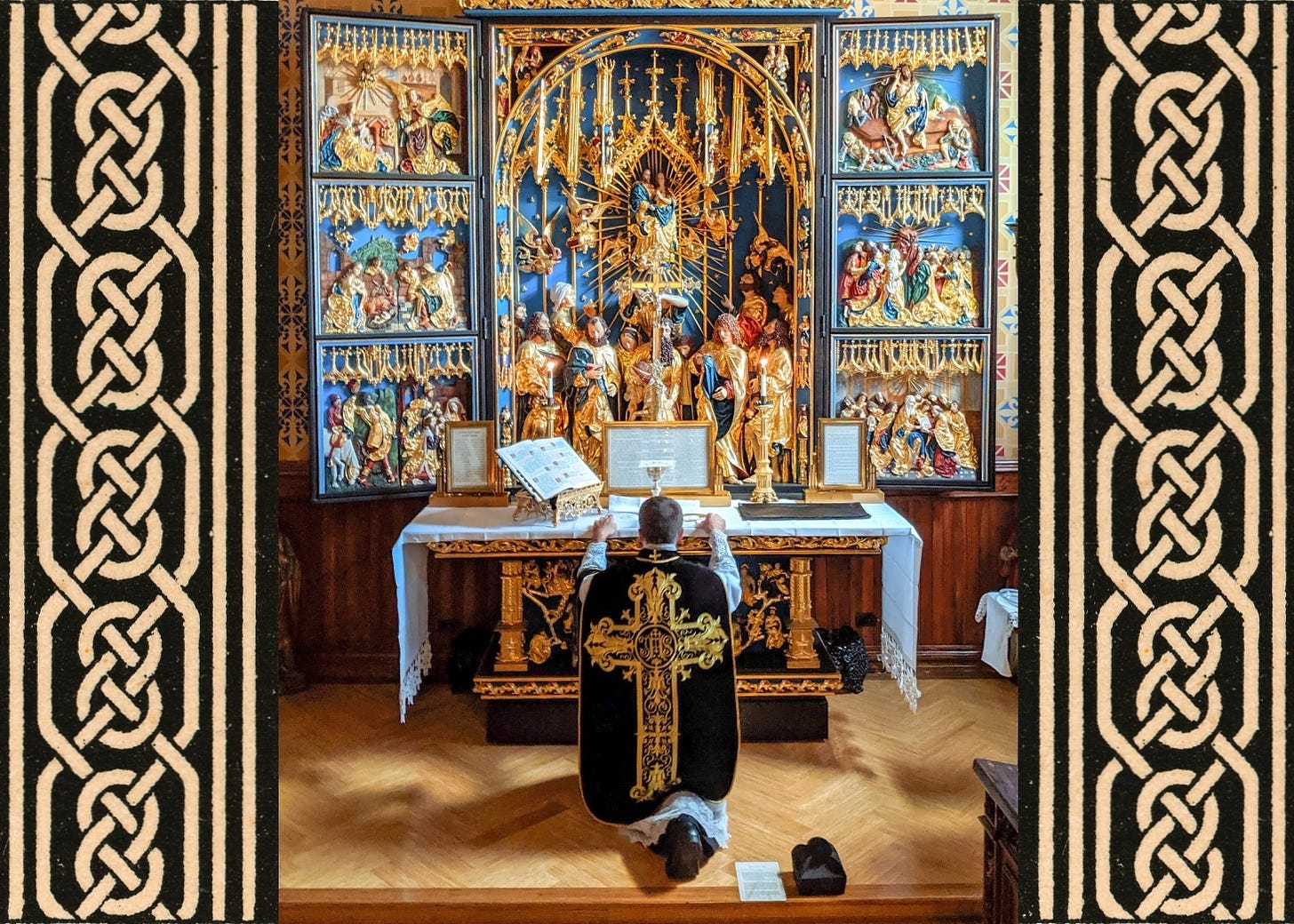

The day before, however, my family and I had gone to a traditional Requiem Mass, sung by a priest friend. The contrast was not just profound, but shocking. Between that day and the following, we were emotionally suspended between two radically different offerings for the dead: one that took death with deadly seriousness, that cared about the fate of the departed soul, and allowed us to suffer; another that shuffled death to the side with platitudes and empty promises. The contrast between Friday’s black vestments, Dies irae, and whispered suffrages and Saturday’s stole-surmounted white chasuble and amplified sentiments of universal goodwill seemed to epitomize the chasm that separates the faith of the saints from the prematurely ageing modernism of yesterday.

I found myself thinking: The greatest miracle of our times is that the Catholic Faith has survived the liturgical reform.

A correspondent once wrote to me about his own similar experiences, and I would like to share his reflections.

I’ve just returned from my grandfather’s funeral. He was a fallen man, whose hope of salvation rests only on God’s infinite mercy and many of our prayers — a reality which was lamentably absent from the prayers and ceremonies of the new order of Christian Burial as I experienced them. I can’t tell whether the priest was selecting only the most sanguine of the options in every case, or whether he was reading the proper prayers constituting the rite, but I was appalled (no pun intended) throughout to hear absolutely no mention of purgatory, atonement for sin, or even the shadow of a doubt that the deceased is already in heaven. Instead, from beginning to end, we were bid to rejoice that the soul of Grandpa stood even now in the light of God’s face.

The overwhelming impression received — even without the tincture of an overly saccharine homily about the sure and certain hope we can have of our salvation — was that my grandfather already sang with the angels, that thus no mourning is necessary, and all prayers for his repose would be superfluous. In fact, the almost off-handed blitheness and platitudinous manner with which the need for tears and mourning was dismissed, in light of his sure salvation, was really quite offensive. As if to say, “Death’s really not such a big deal, after all.”

Of course, the white vestments and pall only added to that impression, so that I was overwhelmed with the sinking and sickening feeling that here, too, the new funeral rite offers us a symbolically denuded, sensitively reconstructed, sterilized and therapeutic experience of Christian mourning that refuses to quake in the face of awesome metaphysical realities, in the face of the fearful judgment seat of Christ (as the Byzantine liturgy puts it).

In short, I felt cheated out of a good mourning. If this is all we get at death, is the Christian life really worth living? Is it really so heroic to die in the faith, if our mourning is so prosaic and our fate so predictable? My father and I declared afterwards, in the presence of witnesses, that we are to be given a traditional funeral at any cost!

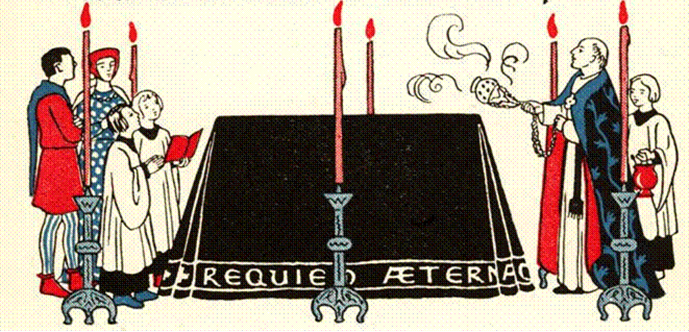

The primary purpose of the traditional Mass for the Dead is to pray for the soul of the departed, that it may be saved and, if in need of purification (as the vast majority of saved souls will be), may be delivered soon from the fires of Purgatory. Hence the ancient Requiem Mass focuses all of its attention on the faithful departed. Psalm 42, focusing on the pilgrimage of this life, is passed over. The priest makes no sign of the cross as he recites the Introit. Incense is but sparingly used. There is no homily. Gone are blessings of certain objects or of the people. A special Agnus Dei begs for the repose of souls (“dona eis requiem”). The prayer for peace among the living is omitted. The Propers are a continuous tapestry of prayers for the dead — the entire liturgy is clearly being offered primarily for an intention other than the people who make up the congregation.

The way that modern funerals have been turned towards the emotional relief of the living and the “celebration” of the mortal life of the deceased is, in reality, a double act of uncharity: first, it deprives Christians of the opportunity to go out of themselves in love by praying for the salvation of their loved one’s soul, the opportunity to exercise a great act of spiritual mercy rather than being the passive recipient of an act of spiritual mercy; second, it deprives the departed soul of the power and consolation of collective prayer on its behalf. It is bad for the dead and bad for the living.

Of course, all of this presupposes an orthodox understanding of the Four Last Things, which can seldom be assumed of clergy or laity after the last Council.

How, how often, and how much we pray for the dead makes a real difference, according to the tradition of the Catholic Church. Prayer, including the offering of the Holy Sacrifice, is a particular human action that takes place in time and space, and therefore has an effect proportionate to the intensity with which it is performed and offered to God. Hence, that we pray intently and frequently for the souls in Purgatory is good for them and good for us.

To be able to do so, we must believe in what we are doing, be reminded of its meaning and its urgency by the very prayers themselves, and have suitable opportunities at our disposal. The postconciliar Church has deprived Catholics of all of these things to one degree or another, and it is only now, in the spreading rediscovery of liturgical tradition, that we are beginning to see the return of earnest prayer for the dead at traditional Requiem Masses.

What, then, are we to do? We must restore the Requiem Mass whenever and wherever possible. We should give priests who can celebrate it stipends and intentions. We should make sure our Last Will and Testament includes specific instructions to have a traditional Latin Requiem Mass offered for us, and leave some funds for it. (It should be noted that any Catholic is permitted to ask for and receive a traditional Latin Requiem Mass, as this booklet from the Latin Mass Society of England & Wales explains in full.) We should attend Requiem Masses when they are offered in our vicinity and pray earnestly for the dead, as we hope someday our loved ones will do for us.

But the problem is worse than you think

To understand how we arrived at the present impasse, we will need to do a bit of theological spadework.

On All Souls’ Day and at every “requiem” Mass—the nickname of the Mass for the Dead, so called from its frequent prayer “Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis”: Eternal light grant unto them, O Lord, and may perpetual light shine upon them — the Introit, the Gradual, and the Communion antiphon all use these words), the traditional liturgy of the Roman Church prays for the souls of the faithful departed. I accentuate the word because it is important that we recognize the full metaphysical weight of what we are praying for specifically.

The fifteenth ecumenical council of the Church, held in Vienne, France between 1311 and 1312, dogmatically defined the following, using the kind of language that every council used prior to, and except for, the Second Vatican Council:

We reject as erroneous and contrary to the truth of the Catholic faith every doctrine or proposition rashly asserting that the substance of the rational or intellectual soul is not of itself and essentially the form of the human body, or casting doubt on this matter. In order that all may know the truth of the faith in its purity and all error may be excluded, we define that anyone who presumes henceforth to assert, defend, or hold stubbornly that the rational or intellectual soul is not the form of the human body of itself and essentially, is to be considered a heretic.

The council fathers here obliquely refer to Aristotle’s doctrine as mediated by the Scholastics, which we may summarize as follows.

Living things grow from within and metamorphose; repair themselves; find their own food; initiate their own acts; reproduce themselves. They exist by nature, not by convention or technology; they possess unity of substance, origin, and actuality.

Contrast that with machines: they are assembled from the outside by, ultimately, a non-machine; they do not grow spontaneously; they need outside repair, they are not self-fueling, they must be turned on and off from the outside, they require control and direction, they do not reproduce themselves, and they are many parts, not one substance (their unity is only one of order of parts).

Similarly, non-living but natural things, like rocks, have natural properties, but they share none of the special traits of the living. Therefore, reasons Aristotle, there must be a principle in living things that vivifies them, makes them to be alive and to be able to do, and in fact to do, all that they uniquely do. This is the soul (in Greek, psyche; Latin, anima).

Modern science has not altered this conclusion one bit, since all it has done is to explain in great detail the material parts of things, all of which are presupposed to living actuality and activity, but none of which accounts for life as such. (For those who wish to read a defense of Aristotle’s view, I recommend Steven Baldner’s “The Soul in the Explanation of Life: Aristotle Against Reductionism.”)

Thus, returning to Vienne, the Church defines that the rational or intellectual soul of man, that which makes him to be and to be alive as the kind of being he is (rational or intellectual), is the “form” of the human body—that which gives the flesh itself its reality, its vitality, its humanity, its functionality. The intellect, as again Aristotle proved, is an essentially immaterial power; Aquinas then demonstrated that such a power is capable of independent existence, although it is not intended to exist independently of the body.

This is why Aquinas maintains that the resurrection of the flesh is “required” for restoring the integrity of human nature. The human person is a body-soul composite. At death, the soul and body are sundered; the material remains dissolve, and the soul receives its eternal reward, either hell for those who die without sanctifying grace, or heaven for those who die in a state of grace—with a time of purification in purgatory for those who need it, which we can reasonably assume to be most of the faithful. All separated souls desire to have their bodies back, and this will indeed occur at the general judgment at the end of time.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, on this point at least reflecting traditional teaching, reiterates the Council of Vienne: “The unity of soul and body is so profound that one has to consider the soul to be the ‘form’ of the body: … spirit and matter, in man, are not two natures united, but rather their union forms a single nature” (CCC 365).

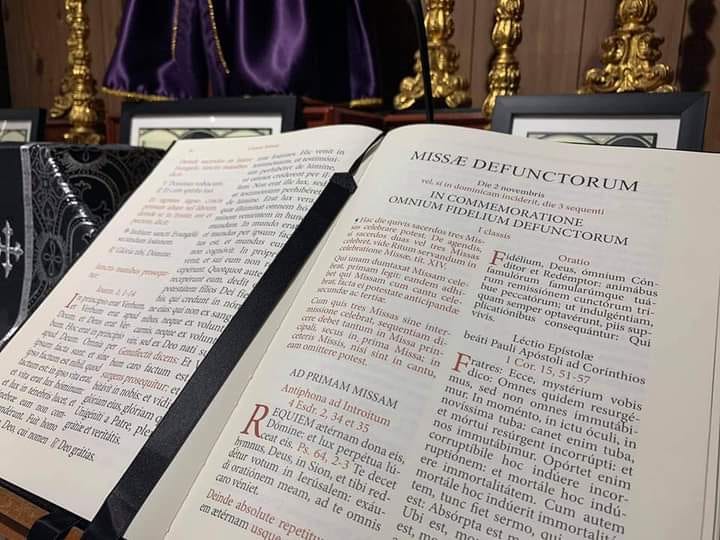

Turning now to the Orations (Collect, Secret, Postcommunion) of the traditional Latin Mass for November 2, what do we find?

O God, the Creator and Redeemer of all the faithful: grant to the souls of Thy servants and handmaidens the remission of all their sins: that through our devout prayers, they may obtain that pardon which they have always desired: Who livest and reignest…

Look with mercy, we beseech Thee, O Lord, upon the Sacrifice which we offer to Thee on behalf of the souls of Thy servants and handmaidens; that those to whom Thou didst grant the merit of Christian faith, may likewise receive its reward. Through our Lord…

May the prayer of Thy servants, O Lord, benefit the souls of Thy servants and handmaidens; that Thou mayest deliver them from all their sins and make them partakers of Thy redemption, Who livest and reignest…

The foregoing prayers are typical of all the prayers in the old missal for Masses for the Dead.

In the Novus Ordo missal, in contrast, these three prayers are heavily redacted. There are many other differences, too, that the reader can see for himself:

Listen kindly to our prayers, O Lord, and, as our faith in your Son, raised from the dead, is deepened, so may our hope of resurrection for your departed servants also find new strength. Through our Lord Jesus Christ…

Look favorably on our offerings, O Lord, so that your departed servants may be taken up into glory with your Son, in whose great mystery of love we are all united. Who lives and reigns for ever and ever.

Grant we pray, O Lord, that your departed servants, for whom we have celebrated this paschal Sacrament, may pass over to a dwelling place of light and peace. Through Christ our Lord.

Did you notice what was missing, and what is has been replaced with? In particular, the word “soul” never appears once.

Again, the above prayers are typical of their genre in the new missal, where we see many lamentable deficiencies:

1. There is the almost total disappearance of the word “soul” (anima). Joseph Ratzinger admitted as much in his book Eschatology: “The idea that to speak of the soul is unbiblical was accepted to such an extent that even the new Roman Missal suppressed the term anima in its liturgy for the dead. It also disappeared from the ritual for burial” (p. 105).

2. The foregoing Collect for the first Mass of All Souls, as we saw above, does not contain any explicit petition for the dead. It speaks of the deepening of our faith in the Risen Christ, and of the strengthening of our hope for the resurrection of the dead. There’s nothing false about it, but it doesn’t give voice to the specific purpose of the Masses of All Souls’ Day, which is supposed to be the function of the Collect.

3. The great Roman Collect quoted above, Fidelium, Deus, omnium Conditor et Redemptor, has vanished from the Novus Ordo liturgy for November 2. It can still be found as an option among the orations for Masses for the Dead, but something strange has happened to it: it addresses the Father rather than the Incarnate Son (“Per Dominum nostrum” replaces “Qui vivis”). And—you guessed it—there’s no mention of the souls of God’s servants and handmaids. It’s been edited out.

What we see going on here is another small example (out of thousands) of the triumph of Modernism, which attempts to adapt the Church’s prayer to the Zeitgeist—in this case, liberal biblical criticism that falsely claims the concept of “soul” has no place in Scripture, and embarrassment at speaking in a way frowned upon by materialistic science, which was already refuted over two thousand years ago by the best Greek philosophers. We see a deviation from the unbroken tradition of the Church’s lex orandi, with profound consequences over time for the lex credendi and lex vivendi. If you change the way Catholics pray, you will change what they believe, and how they act. It’s no wonder that the modern Catholic funeral has become the scandal described in the first part of this article. As André Gushurst-Moore says:

If the idea of the human soul, as something sacred and beyond matter while also existing fully within the physical realm, vanishes from human consciousness, people will live as if their own soul and the souls of others have no existence. It could be agreed, in this sense, that the post-human world has arrived for many in our world, as the sacred and the transcendent disappear from view. (Glory in All Things, 159)

For many years I have been privileged to sing with scholas for the traditional Requiem Mass on November 2 and many other days. This Mass is sublime in every way, especially the chants. Of these, the Sequence Dies Irae—altogether removed from the Novus Ordo Mass for the Dead, but still prayed and sung at the traditional Latin Mass across the world—stands out as an unsurpassable expression of supernatural faith, fear of the Lord, charity for the departed souls, realism and ultimately hope. Hope, after all, is the virtue by which we strive towards difficult things, and salvation, for us sinners, is difficult, at least from a human point of view. Difficult, yes, but worth everything we are, everything we have, everything we can do and suffer.

The photo at the top of this article shows what a true Requiem Mass looks like: facing God, dressed in black, and imploring His mercy for the departed souls… yes, souls.

Against very strong competition, it may be that the transformation from the stark and deep Requiem Mass to the light celebration of the deceased person's life in the Novus Ordo may have been the most catastrophic change of Vatican II - because the people closest to the deceased - their families, their friends - no longer pray for their souls, because they think they immediately arrived in Heaven. Bishop Sanborn has remarked that the theme of these Masses are "Mom's making spaghetti for God," or "Dad's playing golf with God in Heaven."

We can see this change of attitude towards the dead in modern Catholic cemeteries. Instead of images of crosses, rosaries, patron saints, and angels, we see engravings of motorcycles, muscle cars, dogs, cats, fishing rods, even photos of the deceased acting silly. As a student of the History of Religion, this is striking, because it is, whether people realize it or not, a revival of the pagan idea of grave goods to accompany the deceased who will use them in the afterlife. Instead of "On Earth as it is in Heaven," it is the inverse - "In Heaven as it is on Earth."

I appreciate this post more than I can say, Dr. Kwasniewski. Having cared for and watched my husband die recently, I became most aware of the absolute rupture in that which is the Requiem Mass of the Ages for a departed soul and that which passes for the celebration of a life lived in this vale of tears with no reference to the eternal consequences of the temporal punishment for sin. Confession, when the 5 things necessary for a good one have been accomplished, only remits part, not all,of the temporal punishment.

The doctrine of Purgatory has been conveniently put aside and the focus becomes a human ritual where we play up the earthly life of the departed and satisfy ourselves with the declaration that "they're with the Lord", hunting and fishing and bouncing on clouds in Heaven.

If we take this mentality to fruition, then by all means euthanize the elderly because all dogs go to Heaven anyway.

If everyone canonized at a New Right celebration of life is with the Lord, there is no reason for redemptive suffering, thus no reason to care for someone who is dying.

A very slippery slope.