Favorite American Folk Songs and Musicians

From Appalachian Hillbillies to Maritime Canada

“A man should learn all the songs he can.” So says the indomitable Hilaire Belloc, the man who walked from France to Rome in a (mostly) straight line, who braved the mountains of Italy and Spain, and who, not having any mountains in England to challenge him, once walked the 55 miles from the Carfax Tower in Oxford to the Marble Arch of London in just over 11 hours. And he was singing songs all the way — some he had composed, others that he had learned.

To him, singing was a joy, and yet the English, despite having many songs to choose from, “sing less in these last sad days of ours.” He wrote that a hundred years ago, in The Cruise of the Nona. Here’s the full quotation:

A man should learn all the songs he can. Songs are a possession, and all men who write good songs are benefactors. No people have so many songs as the English, yet no people sing less in these last sad days of ours. One cannot sing in a book. Could a man sing in a book, willingly would I sing to you here and now in a loud voice ‘The Corn Beef Can’ and ‘The Tom Cat,’ those admirable songs which I learnt in early manhood upon the Atlantic seas.

To the end of pleasing both Belloc and my readers, I wanted to share some of my favorite folk songs from the American tradition.

Yes, there are many beautiful ballads stemming from the British Isles — Scottish, English, and Irish love songs, laments, and drinking songs — and many of these left their influence on America. These are wonderful, and perhaps more widely known. I love them myself, and wouldn’t discourage anyone from learning them. Yet, I sometimes feel a strange sense of uprootedness when a group of young Americans only knows and sings folk songs from the Old World. The only North American music young people seem to know is pop songs. I’ve noticed this to some extent at both university and parish settings, among Wyoming Catholic College alumni and FSSP young adult groups.

There is something a little strange about people who’ve never been to Ireland singing “as I came over the Cork and Kerry mountains” or the list of places in “Down the Rocky Road to Dublin”: “Left the girls of Tuam…on the rocky road to Dublin…In Mullingar that night…When off Holyhead…The boys of Liverpool.” The lyrics are an excuse for singing a fine tune, and that’s all well and good… but something’s missed when you are singing highly “local” or “placed” songs with no relation to the place. I’ve actually been to two of those places (Dublin and Mullingar), and it’s a funny feeling to sing this song which everyone takes in the “abstract” and all of a sudden to think about having been there.

This is why we should learn some songs about our own homeland, our states and locales. Rootedness in general is an important and scarce thing, and music (in its live and spontaneous form, another unique and scarce thing) gives a unique perspective on place. There’s nothing quite like being able to sing about a place where one lives or has lived, an experience or shared profession relating to the land, the landmarks, the turns of the road you yourself have trodden or driven or ridden.

Thankfully, Wyoming, where I grew up and still live today, is a place worthy of being immortalized in song; and if you live in Wyoming or another western state like Colorado or Montana, it’s easy to find songs about them:

Lights flicker on in a town 'neath the mountain where night first comes down, like a patch of black satin. And the road seems too long between Casper and Jackson when you're tired of traveling alone.

Of course, song is a way of living vicariously, too, and that’s why songs about rambling through the Irish hills, sea-shanties, logging songs, and the like are also appropriate to learn. The world needs more live music, springing up from our souls and on our own lips!

Many of the song’s I’m about to share are about places that are far-away for most of us, even in North America — Nova Scotia, Ontario, the Carolinas, Wyoming — but at least they are “ours” in a way that others are not. But let’s look at some from the Americas. (Along the way I’m going to include a few non-American ones as well, because they are performed by the same American musicians and are too good for me not to include.)

Music in the Home

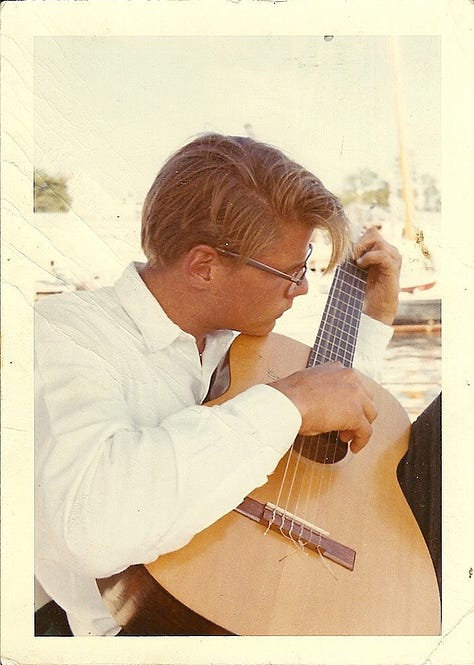

Gordon Bok, some of whose lyrics have already been quoted above, deserves our attention. Only a “half-professional,” Bok was a sailor before he was a musician; and when, in the 1960s, he began to experience success concertizing, he refused to go full-time with performing; he wanted to preserve the enjoyment of amateur music.

For Bok, music is first and foremost to be enjoyed live, and by playing it yourself. That’s what makes it “folk music” or music of the people:

A large part of the music I sing has been given or sent to me over the decades, simply because people have heard what I sing and want to share something they find important. I have to trust that there will always be people who need the beauty and wisdom in the old songs, who simply find their awe refreshed in the mystery in them. I know there will always be those who need to make music, from their own or from their people’s experiences. Who knows what “folk” means today… for half a century, people have been painting that label on whatever they’re trying to sell. But there’s an intense electric connection when someone like Cathal McConnell sits you down in a kitchen and actually teaches you his version of an old song that was given to him in the same way. I liken that experience to what it might be like to climb down into the Grand Canyon on your own two feet (in your own sneakers).

Bok used to perform in large auditoriums, but prefers the house concert style:

To me it’s back to where it belongs, in peoples’ homes. House concerts, of course, they’re just wonderful. You’re done working, then you toddle off to bed.

Cathartic working music

Of his involvement with sailing, Bok said:

I’ve spent a lot of my time among “maritime” people, absorbed stories, and drawn from my own experiences as well as from many other people’s experiences: stories they’ve told me, poetry they’ve written, and things I’ve experienced because of the music I’ve made or gathered and passed on.

An important category of American folk music is working songs: ones to sing while you work, but especially ones that meditate on the profession, and its joys and hardships. It seems like there are few completely positive songs in this genre, especially when it comes to mining and fishing. Coming to grips with such grueling and dangerous work necessitates some sort of catharsis. That’s what I believe is going on in the songs that speak of how “the winters drive you crazy and the fishing’s hard and slow” or of the fate of miners buried alive.

Few are as poignant as the ballad “Three Fishers,” written in the 19th century by English poet, novelist, and Anglican priest Charles Kingsley. In it, the drowning of the fishermen and the mourning of their wives gives rise to a haunting refrain:

Three fishers went sailing out into the West,

Out into the West as the sun went down;

Each thought on the woman who lov’d him the best;

And the children stood watching them out of the town;

For men must work, and women must weep,

And there’s little to earn, and many to keep,

Though the harbour bar be moaning.Three wives sat up in the light-house tower,

And they trimm’d the lamps as the sun went down;

They look’d at the squall, and they look’d at the shower,

And the night wrack came rolling up ragged and brown!

But men must work, and women must weep,

Though storms be sudden, and waters deep,

And the harbour bar be moaning.Three corpses lay out on the shining sands

In the morning gleam as the tide went down,

And the women are weeping and wringing their hands

For those who will never come back to the town;

For men must work, and women must weep,

And the sooner it’s over, the sooner to sleep—

And good-by to the bar and its moaning.

Here is the poem set to music by Nathan Rogers:

A favorite of mine when it comes to nautical themes, “Farewell to Nova Scotia” was adapted around World War I from an 18th-century Scottish song into the version we know now. It is the song of a sailor lamenting that the time has come to sail on his warship from the rugged Nova Scotia and perhaps join his three slain brothers in battle:

For evidence of how different a character performers can give to a song, listen, after that rousing rendition, to Cindy Kallet and Gordon Bok’s mournful, slow, and melancholic harmonization:

The next song, written by the English musician Jez Lowe, takes inspiration from a gravestone on the Northern coast of England, where local people had buried the bodies of sailors from a Norwegian fishing boat that had sunk offshore in a storm. Not knowing any crewmembers’ names, they simply put the name of the ship on the stone.

This is the original recording by Jez Lowe and Jake Walton in the 1980s:

And the beautiful, more recent version by Gordon Bok:

As to the lyrics, I’d like to point out how the internal rhymes or partial rhymes at the beginning of lines, not just the rhymes which end them, add more cohesion to the song (apparently rewritten quite a lot):

Sleep, why wake me with these dreams that you bring? Dreams came to me where I lay Deep the melody the wild waves sing My love is far, far away Chorus: Oh pity the heart, the wild waves part My love sails the bonnie barque the Bergen They heap their nets upon the decks by the light Dreams came to me where I lay Then creep out gentle in the dead of night My love is far, far away (Chorus) They reap their harvest from the cold night sea Dreams came to me where I lay It reeks with herring in the hold for me My love is far, far away (Chorus twice) Steep waves ride above his cold, fair head Dreams came to me where I lay Oh keep him safe to lie here in my bed My love is far, far away (Chorus) It weeps with rain tonight where my love lies Dreams came to me where I lay Oh wipe the foreign sand from out of his eyes My love is far, far away

Here are three other cathartic songs of the sea:

One of my favorite “profession songs” from the Bluegrass tradition is the “Miner’s Silver Ghost,” from an age when miners and railway workers ran the world:

I love how “itchy” the tune is, and how it gets under your skin with just the right amount of speed, driving base, anticipation, and haunting slide-guitar notes. “Whenever some mountain slides and men are lost” . . . yes, whenever that happens.

Here’s another mining one, describing a mine named “The Gin and the Rasberry,” and how the festive summer gold rush turned dark in the cold winter when after much disappointment one man found a vein and was soon found dead:

To the far north lies Canadian logging land: and I must confess a little romantic jealously for the rustic life of logging. Ah well, I’ve probably missed my window of opportunity for that, but if I ever have a son who wants to go logging for a summer job — why then, he’d have my blessing (the same is true of commercial fishing, especially in Alaska). Here we find another genre of work song.

Bill Staines’ “Logging Song” is often what I start early work mornings with (along with strong coffee), and you’ll see why after about five seconds of listening. It’s probably the only purely positive “work song” on the list — no one dies or is eaten by flies, gets murdered, etc.

Lie of the Land

Singing about your very own state is special in a way no other song can be. One of the most special to me is “Wild Birds,” which speaks of the long roads leading through Wyoming to Montana, and the friendly, simple folk who live in the small towns:

John Denver is not the most breathtaking or original musician, to my ear, but he did get a few ballads really right, and they are thoroughly American. None more so than “Country Roads”. I’ve already mentioned John Denver’s “Song of Wyoming” in other articles, but here it is again.

Some might find this funny, but I prefer other musicians’ renderings of Denver’s songs. He usually padded his songs with too many special effects, rock-band-style backup, and ’80s synths. He wrote great songs but performed them in a very mediocre fashion. (Not to be outdone in terms of performance variety, one should really listen to the “West Jamaica” version of “Country Roads.”)

Besides the western US and the Maritime east coast, another place that has a very special culture of music is the Appalachians, birthplace of Bluegrass, and home to many beautiful songs about different parts of the Carolinas, Tennessee, and, of course, the West Virginia we already heard about.

Here are my three favorite Bluegrass pieces about the Carolinas:

Bok’s love of Maine as a place is also evident. Asked if he finds it harsh, he says:

Well, I consider it a kind land. I love the quiet of the winter, the silence of snows. The people really, that I have hung out with in my life, they know how the world works. They’re out in it, working with it, farmers, fisherman, woodsmen, boat builders. I think it’s just a wonderful place to be with the world.

Conclusion

I believe Belloc and Bok would have got along quite well. If any man “knew as many songs as he could,” Bok is that man who lived up to Belloc’s admonition. As Bok says:

I know so many songs. They’re like horses. You gotta feed them and let them out. You gotta exercise them. And if you don’t they’re gonna wander off. You hope that somebody else will feed them. That’s why I record them now.

Most if not all the songs I’ve shared here can be found online, with lyrics, chords, and sometimes even melodies (so you don’t have to learn it just by ear). I hope you will enjoy listening to them, and even learn to sing a few. Bok describes music in his home growing up:

Some holiday gatherings of my mother’s people—after the food was done, and the toasts were sung—the singing moved into the living room where the instruments were, and it kept going there as the room darkened from afternoon to evening. I remember mostly the singing, the blend of family voices in slow solo ballads or harmony, and the fact that they didn’t need light to keep on singing. They played guitars in various forms, the odd banjo, harmonica, whistle, or piano.…they walked in the woods singing, they sang while they washed dishes. They didn’t make a big deal of it. I couldn’t sing in tune, but no one ever told me not to sing in that family.

I hope that will describe my family one day. And yours too.

In consideration of the work that went into this article, please consider putting $5, $10, or $15 in my tip jar:

Thank you for your support of this and previous articles —

I enjoy writing for you!

So much thanks to give for, and so much to say about, this excellent piece. Folk songs and singing constitute a critical piece of Catholic flourishing. I've been planning a festival in North Carolina that drives at this very notion. For any readers who happen to live in the surrounding region of the US, come to the Kingfisher Folk Fest in Candler, NC on August 2 and experience the premises of this piece in action. Jam sessions, ballads, called dances, storytelling, and festivity are all on the agenda. All proceeds go to a classical Catholic school in the area.

For full details, see kingfisherfest.com.

You have struck a very wonderful chord (no pun intended). I haven’t listened to everything yet, though I plan to later today. But what I remember from my youth is precious: my Irish grandparents and their four daughters and sons-in-law would clear the dishes from “the groaning board” (the table laden with a sumptuous meal for a holiday) and start singing with harmony and some instruments: Old Black Joe, The Mountains of Mourne, Low Bridge, and countless others. As kids nearing adolescence, we would sometimes roll our eyes. But we loved it just the same. It was warm, bringing everyone together, sometimes very moving because these oldsters would feel so much from the music. When I was younger, we would fall asleep to the music and feel very safe. Thank you for reminding me. Like dancing, this tradition has fallen away so much that we don’t remember our roots.