St. Robert Southwell: Bethlehem’s Poet

The Mass and the Missions, Part III (2 of 2)

The Food of Love

Fr. Southwell’s corpus of writing shared one purpose with his priestly ministry: to feed the starving souls of his spiritual children. Fr. Devlin makes a most interesting observation in his account of the 1586 meeting of St. Robert and the great composer William Byrd:

The beauty of church music was one of the chief means by which the recusants kept up their spirits. Between Southwell and Byrd there is no record of any further meeting; but it is natural to suppose that there were many. Byrd was engaged at this time in setting to music the poems contained in his Psalms, Sonets, and Songs of Sadness and Piety, which did more than anything to preserve the medieval lyric in English poetry; and it was probably with his help that Southwell first became acquainted with contemporary English verse in its current manuscript form.1

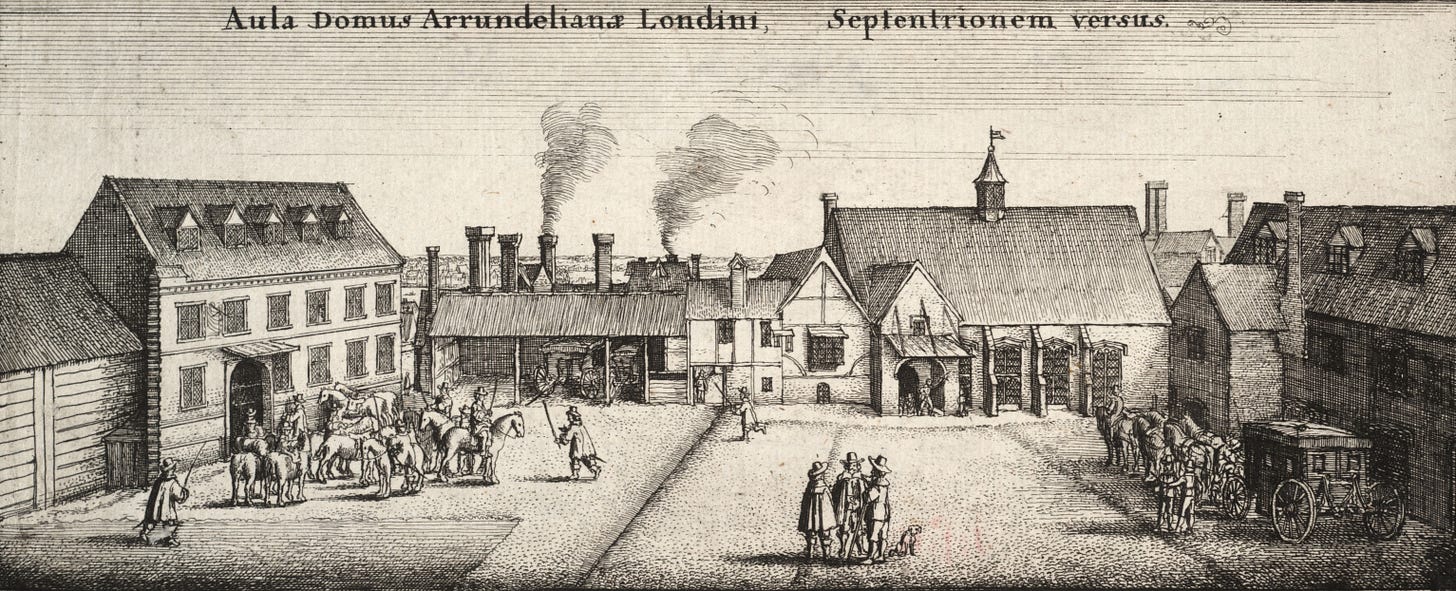

It is likely that most of Southwell’s poetry was composed in his year of secret residence in the London house of Lady Arundel, around 1590 (see image at the top of the article, showing Arundel House c. 1646). There, he meditated on the writings of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the Scriptures, and the Church Fathers. From this intense period of daily isolation and dangerous nightly ministry, Southwell’s mystic voice emerged.

The great twentieth-century writer Sigrid Undset noted:

In his poems it is above all the mystery of Christmas that occupies his thoughts. Circumstances had made him a cavalry leader in the militia of Jesus Christ, as one of his fellows calls himself. Now the soldier was permitted for a short time to kneel before the manger and do homage to his King in His childish grace and helpless littleness…his Christmas poems have a dark golden luster of their own. And there is an unforgettable power in his image of Christ—the eternal God who unwearied through eternity supports the earth on His finger-tip and encloses all creation in the hollow of His hand—but in His humanity breaks down and falls beneath the weight of a single person’s sin. And his vision of the Child Jesus appearing as a blazing meteor over the frozen fields of earth—as a ball of fire from the glowing love which is the primal element behind all things created—is strange and startling in the interplay of its Renaissance extravagance, the naturalism of its imagery, and the unrestrained passion of feeling.2

In her important study examining the link between Southwell’s “Burning Babe” and medieval iconography of the Proleptic Passion (the image of the suffering Infant Jesus), Dr. Theresa Kenney points out that Southwell’s Infant has a direct relationship with the time-suspending “Hoc Est” of the Mass:

In this poem Southwell fuses the language of sacrifice and the language of love to collapse the distance between God and man, in particular, to collapse the distance between man’s temporal life and Christ’s historical birth and death. The heat and fire that signify both love and violent death warm and light up the heart of the solitary speaker: “supris’d I was with sodaine heate. / Which made my hart to glowe.” The fire is “neere,” and the fire is the Child. The first, a portent of dissolution, at the same time dissolves every distance between man and the newborn Child: it is indeed “Christmasse day,” the day of the Mass of Christ, and his heart glows with infectious heat.3

What was it about the beautiful Babe that captivated the poet-priest? Though young, He was wise. Though small, He was strong. Though man, yet He was very God. The Christ Child, pursued violently by so many would-be conquerors, was the mighty Hero, the Prince of Peace, the Light that was the Life of Men. He lived, a spotless Lamb in Southwell’s hands.

Growing up as an Anglican, Byrd's music formed a significant part of my spiritual development. (Along with that of his mentor, Thos. Tallis.)

His conversion story is beautiful; it seems significant for the Ordinariates and their culture that Byrd's work is shared in the deepest possible way by the Catholic Church and the liturgical traditions surviving in Anglicanism, since his work is a major part of Anglican culture, and he will someday share in the beatific vision.

Hopefully, those who remain in his church of origin will continue to come into fuller communion with Rome.

Southwell as someone who kneels at the manger already knowing the cost changes everything. No cozy Christmas. No safe beauty. Just heat, danger, and devotion under pressure.

The way you tie the Burning Babe to Mass, time collapsing, fire as love and sacrifice at once. That’s not poetic ornament. That’s theology that scorches.

Quietly devastating piece.