The Mass and the Missions, Part I: The Passion of St. Isaac Jogues

Author’s preliminary note: We rightly love the Traditional Latin Mass for its great stability and solemnity. This spiritual greatness, which has brought countless millions of souls to their knees in adoration of Christ, and imbued them with an unshakable love of His Sacrifice, also made the Traditional Latin Mass the most powerful evangelistic prayer in the history of Christianity. This has proved true even when the Mass was said in the most hostile and austere environments, on the barest altars adorned only with the whisper of the priest. This essay is the first in a series that will explore the missionary fruitfulness of the Mass. May the blood of the missionary Martyrs, offered in union with the Precious Blood of Jesus at the altar, set our hearts aflame, that we too become luminous witnesses to His glory.

On the eve of the Assumption, 1642, the Jesuit St. Isaac Jogues was dragged to a platform amid the gleeful madness of his Mohawk captors. His years of heroic labor among the native peoples of New France seemed to be consumed in a living nightmare. Wounded and gangrenous from a deadly ambush, he had endured starvation and the brutalities of a forced march for nearly two weeks. In a diabolic frenzy, the Mohawks had gnawed to shreds all but two of his fingers. Now he and his few remaining companions stumbled through a gauntlet of clubs up the hill of Ossernenon under a continual rain of iron rods, fists, and knives.

Amid this terrible scene, there must have been something calm and otherworldly in the face of the tormented Jogues, some spiritual grace that radiated from his mangled body. Some odor of living sacrifice. Something priestly. His triumphant enemies couldn’t stand it.

“Come, let us caress these Frenchmen,” cried an Iroquois captain. A captive Christian woman, threatened with death, was forced to saw off his left thumb with a knife. Thus, all in a moment, Jogues’ canonical digits, and his ability to say Mass, were lost, as he thought, forever.

As he gazed at his bloody and wasted hands, amid the smoke, the din, and the ritual terror, St. Isaac offered them to God, as he felt he would never again offer the Immaculate Host.

He bent to pick up the remains of his thumb, and prayed,

I present it to Thee, O my God, in remembrance of the sacrifices which for the last seven years I have offered on the altars of Thy Church, and as an atonement for the want of love and reverence of which I have been guilty in touching Thy Sacred Body.1

The missionary, even in the depths of his agony, lived and died in union with the ancient Mass.

The Mass was the heart of his labor, the great key to his success, the surest solace in all his infirmity and failure. The Mass gave him the courage to lift up his heart to Christ in the midst of unspeakable deprivation and sorrow, for its words and gestures reminded him solemnly, daily, that the Priest, at one with the Lamb, was a living oblation. How else can one explain the dauntless love for God and man that the long winter’s bitterness could not chill and the inhuman fury of his enemies could not overcome?

He had caught spiritual fire from the altar of Sacrifice, and would not rest until the wild Northern lands were ablaze, for the Mass made the proud native peoples into converts, and converts into saints. In union with the Sacrifice, at the very ends of the world, he offered his own body to Christ, his King. The Mass made the missionary a martyr.

A Testimony in Blood

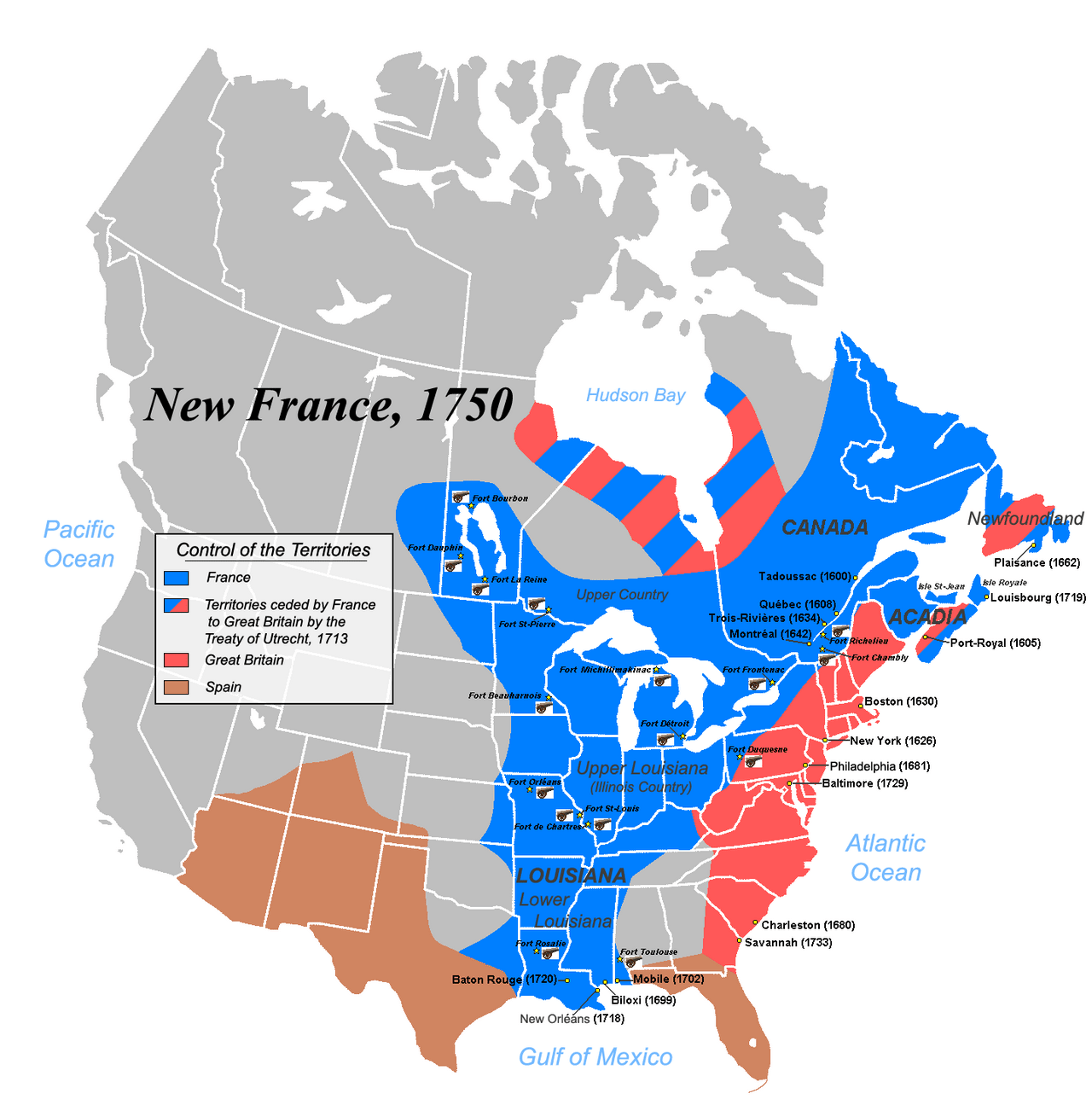

The Relations des Jésuites de la Nouvelle-France, or Jesuit Relations, are a fascinating compendium of the labors of the Society of Jesus in New France, that great viceroyalty of the “Most Christian King” which by the 18th century stretched from Hudson Bay to the Mississippi Delta, and from Port-Royal to the Western plains.

Comprising some 73 volumes of reports taken between the years 1610 and 1672, The Relations are a monument of historical scholarship and a Catholic treasure. They represent an extensive account of the native peoples in New France, written with care by the Jesuit missionaries, who sent detailed writings of their experiences back to their superiors. These accounts were often written scratched on scraps of paper against the shadows of dim firelight, in crowded longhouses or birch cabins filled with smoke which caused blindness in European eyes, with no privacy or space for calm recollection.2 Father John O’Brien notes that,

Considering the difficulties, it is a wonder that anything at all was written and dispatched. Jogues wrote some of his letters with a hand on which there remained but one whole finger; blood from the wound stained the paper. Gunpowder was his ink; the earth, his table.3

Each account from The Relations bears witness to their unshakeable hope in the rich spiritual harvest to come, though the missionaries walked ever in the shadow of death. Willingly and consciously, they made their lives an imitation of the Holy Sacrifice, frequently invoking the Precious Blood as the mystical guarantor of their missionary success.

Wilderness Chapels

The Relations testify continually to the missionary power of the Mass, which so deeply impressed the souls of the Huron-Wyandot, the Algonquin, Abenaki, and dozens of other tribes, of widely diverse languages and cultures. Whether he lived his life peaceably or by constant war, whether he was settled or nomadic, whether he was the friend of the Blackrobe or his deadly adversary, the Native American was a living paradox: carnal and restless in his desires, he was at the same time imbued with a sensitivity to the mysterious world of the spirit, and with an awe of sacrifice. Thus, the Jesuits spared no effort to ensure that community life in the Missions revolved around the little chapels, built with the humblest materials but also with the greatest reverence.

One Father describes a memorable feast of Corpus Christi spent on a voyage to the Tadoussac mission.4 Howling winds and inclement weather threatened his journey. Yet, in an austere chapel made only of bark and poles laid in bare rock, accompanied by his fellow Frenchmen as well as Christian and pagan Native Americans,

I spent the great feast of our Lord…—very poor in worldly goods, but richly provided with the blessings of heaven.… I erected a little Altar that I might say holy Mass; they aided me with so much affection that I was greatly moved thereby; on seeing that the place where I should walk was very damp and muddy, they threw a robe upon the ground to serve me for a carpet.… I stretched a little altar cloth across the cabin, to separate the faithful from the unbelievers; then I began holy Mass, not without astonishment that the God of gods should stoop once more to a place more wretched than the stable of Bethlehem.5

Amid the crashing pines and the swaying birch, Christ silently took possession of His Kingdom, raised aloft in the hands of the priest. The pagans were struck with awe. This was not like other sacrifices. The unnamed Father noted that they “who had not been baptized maintained a profound silence during this divine Sacrifice, and they also had a great desire to be Christians.”

Shorn of its ornaments, amid great poverty, danger, and nearly insuperable differences of language, this ancient Mass indeed drew all men to Christ, fortiter et suaviter, in strength and sweetness.

The Beauty of Thy House

Where the wilderness became a settlement, such as at Sault Ste. Marie or Saint Joseph, the Jesuit missionaries would attempt to find a more permanent and fitting home for the Blessed Sacrament. Initially, this would be a mere corner of a hut, partitioned with a sheet if available. The same unnamed Father recounted of his mission to the Nipissing6 peoples that “We say holy Mass every day in their cabins, making a little recess, or a little Chapel, with our blankets.”7 In this way, the Christian natives were honored, and the priests could catechize their little flock family by family.8

Crucial to the stability of the Church in New France were log cabin chapels where the priests could regularly say Mass, lead devotions, and teach the truths of the Faith. They ornamented these chapels with the best materials they could find, often evergreen boughs, tinsel, and religious pictures brought with great pains over hundreds of miles. Throughout The Relations, the priests describe their consolation in seeing the good fruit brought forth by their efforts to celebrate Sundays and the principal feasts with all solemnity. Fr. Jérôme Lalemant recounted:

The outward splendor with which we endeavor to surround the Ceremonies of the Church; the beauty of our Chapel (which is looked upon in this Country as one of the Wonders of the World, although in France it would be considered but a poor affair); the Masses, Sermons, Vespers, Processions, and Benedictions of the Blessed Sacrament that are said and celebrated at such times, with a magnificence surpassing anything that [their] eyes have ever beheld,- all these things produce an impression on their minds, and give them an idea of the Majesty of God, who, we tell them, is honored throughout the World by a worship a thousand times more imposing.9

Yet the souls of the natives were far more precious to the missionaries. The missionaries, not content with the mere attendance of their converts at Mass, taught them simple prayers in both their own language and in Latin, and composed beautiful hymns for them to sing. The most well-known of these hymns is the Huron Carol,10 composed by St. Jean de Brébeuf. The native peoples were gifted with an extraordinary love for music and singing, and so polyphonic motets were also composed for their devotion. The Mass might then be adorned with the beautiful voices of the missionaries’ spiritual children.

The Relations concerning Madame de la Peltrie11 and the seminarists (school children) of the Ursuline foundation of St. Joseph at Sillery recount that,

Now as these children hear the Holy Mass every day with the Nuns, and as they hear them sing every day during the elevation of the blessed Sacrament, they have remembered one of their motets so well that they sang it finely at St. Joseph, in the presence of their Christian relatives, when the sacred Host was elevated at the midnight Mass. They sang also before the holy Mass a spiritual Song, composed in their own language, upon the Birth of the Son of God. [They] took up the strophes finely, and sang them one after another in good time.

Thus, while the far distant stones echoed the whispers of the pilgrim priests, the children sang for Christ the King in all the fullness of their innocent hearts.

The Mass, with its ancient, mystical holiness, was a true homeland for the Christian Native Americans in brief lives which were often marked by dislocation, poverty, and violence. Faith illuminated the darkness, and love for God bloomed in souls long enslaved in idolatry, now captivated by the beauty of the Incarnate Savior new-born upon the Altar. They had a special love for Christmas Midnight Mass, with its candles which made the night like day, and looked forward to receiving Communion then with great fervor. Father Barthélemy Vimont recounted that,

[They] have a particular devotion for the night that was enlightened by the birth of the Son of God. There was not one who refused to fast on the day that preceded it. They built a small chapel of cedar and fir branches in honor of the manger of the infant JESUS; they wished to perform some penance, to prepare themselves for better receiving him into their hearts on that holy day; and even those who were at a distance of more than two days’ journey met at a given place to sing hymns in honor of the newborn Child and to approach the table whereat it was his will to become the adorable food. Neither the inconvenience of the snow nor the severity of the cold could stifle the ardor of their devotion. That small chapel seemed to them a little Paradise.12

In the Footsteps of Christ

The Mission priests, daily confronted with starvation and death, were often astonished at the humility and the faith of their converts, who would endure great hardship to be present at Mass:

neither the mountains nor the valleys, nor the length of the way, nor the ice, nor the snows, nor the wind, nor the cold, [prevented] them — either the men, or the women, or the children — from coming every day to the chapel in order to hear there holy Mass.13

Both the priests and the people knew that the Mass and the Sacraments kept them from sliding into their former paganism; both Blackrobe and Brave greatly feared going too long without this necessary spiritual strength, for the powers arrayed against them were fierce and legion. Thus, when the foraging or hunting season forced the tribes away from their Mission chapels, the priest would (if possible) accompany the tribe in their wandering, bringing the chapel to them. In the extraordinary account of Father Sébastien Râle,14 Father Râle describes his efforts to provide a fitting home for the Holy Sacrifice in a “flying chapel” of birch bark:

As soon as we have reached the place where we are to spend the night, they set up poles at certain intervals, in the form of a chapel, they surround it with a large tent-cloth, and it is open only in front. The whole is set up in a quarter of an hour. I always have them take for me a smooth cedar board, four feet long, with something to support it: this serves for an Altar, above which is placed a very appropriate canopy. I adorn the interior of the chapel with most beautiful silk fabric; a mat of rushes colored and well wrought, or perhaps a large bearskin, serves as a carpet. These are carried all ready for use, and, as soon as the chapel is set up, we need only to arrange them.… If the journey be made in winter, they remove the snow from the place where the chapel is to be placed, and then it is set up as usual. Every day we have evening and morning prayers, and I offer the holy Sacrifice of the Mass.15

To fulfill the desire of his people for Mass, Father Râle, like his brother missionaries, would go for days without eating and sleeping, trekking across the untamed lands with his people in search of elusive game, vegetation, or fish. When he did eat, he ate no more, and often far less, than the poor fare of his spiritual children. He spent thirty years cheerfully enduring every hardship for the souls of the Abenaki.

He wrote to his brother of his efforts to ensure the solemnity of Divine Service in his settled mission near the Kennebec river:

I thought it my duty to spare nothing, either for its decoration or for the beauty of the vestments that are used in our holy Ceremonies; altar-cloths, chasubles, copes, sacred vessels, everything is suitable, and would be esteemed in the Churches of Europe.16

He trained forty young men to serve not only at Mass, but to chant the Divine Office for Benediction and processions.

His zeal so deeply touched his people that when they were threatened with annihilation by the English, who offered the tribe survival on the condition of expelling the incendiary Father Râle and replacing him with a Protestant minister, a Chief wrote them back courageously, “I tell you that I hold to the prayer of the Frenchman; I accept it, and I shall keep it until the world shall burn and come to an end.”17

The Captivity of Jogues

As he languished in bondage during the winter of 1642, did Isaac Jogues too feel that the ends of the world had come upon him? Earlier that year, in the relative security of his chapel at Sault Ste. Marie, he had offered himself to God at the altar for the salvation of the Hurons, and he had felt that his prayer was accepted. Now he found himself abandoned, bereft, utterly unworthy. His companions had been martyred, shedding their blood for Christ; but he, for his complacency, had been chastised.

After his torment on the scaffold, he had been adopted by the chief who had captured him, and thus, the mutilated Jogues lived, but was reduced to the condition of a slave. The merciless nomadic course of the Mohawk winter deer hunt reduced him to little more than bone and rags amid the freezing snow. He was given the job of a pack animal. Jogues was meek with his captors, who alternately neglected and harassed him, until they began to blaspheme, and attempted to coerce him to worship their gods. Then he, forever a priest, would rebuke them with boldness.

Jogues called this enslavement his “Babylon,” and when he could, he sought precious solitude where he might weep alone with his God. O’Brien recounts that,

Wandering off into the wilderness, he would recite the Rosary, repeat passages from the Scriptures, and read from The Imitation of Christ. In some lonely spot, he would carve the figure of the Cross into the trunk of a tree and there kneel in prayer for long periods.18

In his grief, did Jogues whisper the words of the ancient hymn to himself? Crux fidelis, inter omnes, arbor una nobilis. The tree became an altar for him—the bare and bereft altar of Good Friday, an endless Good Friday. Under the trembling bough and branch, he clung to Christ Crucified, haunted by the night of interior fear and desolation, and the memory of so many Masses he had offered in that Mission-exile, distractedly, “wanting love and reverence.”

Fr. Lalemant, the Jesuit chronicler, adds,

This good Father lived only by the Cross, he meditated only on the Cross, he dreamed of nothing but the Cross, his mind was enlightened by the Cross; he made loving Litanies upon it, which were found, after his death, on scraps of paper, whereon he had also written some words in the Iroquois language.

A true son of St. Ignatius and a member of the Company of Jesus, Jogues prayed, doggedly, resistantly, in this poorest of wilderness chapels, making the Spiritual Exercises for forty days as the cold cracked his bare legs and thighs. In his own words,

The snows being already deep, I found myself half dead in hunger, in cold, and in nakedness; I was the mud and the mire of those Barbarians, the shame and the sport of men. I suffered mortal anguish in my soul at the sight of the omissions and sins of my past life; the pains of the death which I was to expect, in a little while, at the hands of those Barbarians, as they told me; and the perils of Hell that surrounded me on all sides.

I distinctly heard a voice which condemned the pusillanimity of my heart, and which gave me warning, sentirem de Deo in bonitate, that I should fix my thoughts upon the goodness of my God, and cast myself entirely upon his bosom. I heard these other words, which I believed were from Saint Bernard, Servite Domino in illa charitate quæ foras mittit timorem; meritum non intuetur,—“Serve God in the charity and love which expels fear; he does not turn his eyes upon our merits, but upon his own goodness.” These admonitions were given to me very opportunely, for I felt that truly I was not in a loving and filial fear, but in a servile dejection.…

Now these words changed me in a moment; they banished my vexations, and threw me into a fire of love so vehement that, before having returned to myself, I pronounced with great impetuosity these words of Saint Bernard: Non immerito vitam ille sibi vindicat nostram, qui pro nobis dedit et suam,—“Not without reason does he ask our life, who has given up his own for us.”19

The wild hills rang with Jogues’ exhalation, the words of the holy Cistercian echoing the immortal priestly prayer of Loyola: Suscipe. Before the altar, Jogues had laid down his life in imitation of Christ, the True Victim, in full Faith that He who received his life would restore it in eternal abundance and spiritual grace. This hope would not be disappointed. Jogues returned to his captors transfigured, embracing his living death Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam.

His Final Offering

The tale of St. Isaac Jogues’ eventual harrowing escape from captivity and his dramatic return to France on Christmas morning of 1643 has flowed from innumerable pens. In what must have seemed to him a strange dream, Jogues, once a slave, was fêted around Europe, the hero of the Catholic people and an honored guest of Royalty. When the Jesuits petitioned Pope Urban VIII on Jogues’ behalf for a dispensation that he might once again say Mass, the Pope famously replied, “Indignum esset Christi martyrum Christi non biberem sanguinem”—it would be shameful that a martyr of Christ not be allowed to drink the Blood of Christ.20

What must have been Jogues’ sentiments as he leant over the altar, his crippled hands cradling the chalice for the first time in twenty months? Humble silence lowers a veil over such a moment of unspeakable intimacy.

Jogues had given his hands to Christ the Priest, who had taken them for a season, to give them back again. Jogues was caught up in this loving colloquy of divine generosity, and he could not deny His Lord. Thus, astonishingly, he requested permission from his superiors to return to the land of the Iroquois. St. Isaac Jogues instinctively knew that the consummation of his sacrifice, long delayed, was at hand. They gave their consent, and he returned to North America. On his final mission, having a presentiment of his death, he wrote to a Jesuit brother,

If I be employed in the mission, my heart tells me: Ibo sed non redibo, “I shall go, but I shall not return.” In very truth, it will be well with me, it will be a happiness for me, if God will be pleased to complete the sacrifice where I began it.21

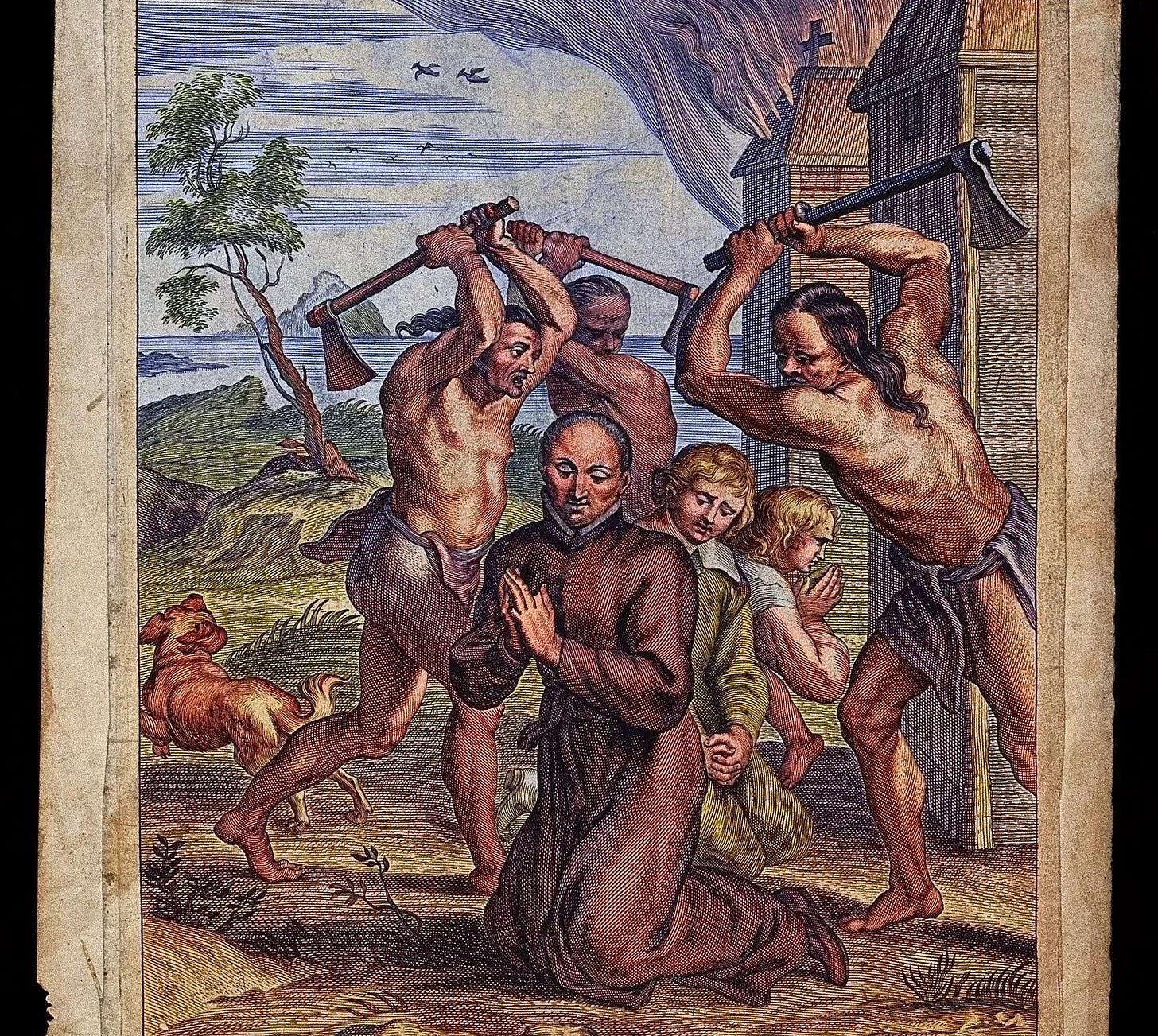

Jogues made his final oblation to his Lord on October 18, 1646, tomahawked on the head as he bent down to enter a Mohawk cabin. For him, it was the doorway to eternity, as the gauntlet of his torment had been, in his own words, “the narrow way of Paradise.”22

The Children of the Martyrs

Under the mysterious dispensation of God’s Providence, and very often hidden from the eyes of men, the children of the Martyrs ever increase. The blood of the Martyrs is a seed that never fails.

Are you one of the innumerable souls who travel dark and dangerous roads, that you might worship God according to the traditions of our fathers? Have you been among those who have lovingly adorned a makeshift chapel set up in a parking lot, finding in that improbable place of holy respite “a little Paradise”? Have you knelt on a Sunday outdoors in freezing rain and snow, or in a hotel conference room, or in a humble home chapel? Have you, giving everything, found yourself alone, forsaken, and scandalized, but for the silent Christ in the tabernacle? In the anguish of your hearts, finding yourself helpless and at the mercy of powerful men, deprived of your beloved churches, the traditional Sacraments, or your vocation, do you offer Christ but poor and mutilated service?

Take heart. Sentirem de Deo in bonitate. Fix your thoughts only upon the goodness of God, and cast yourself entirely upon His Sacred Heart. For all that we suffer, we have not suffered half as much as our Fathers, nor with but a small measure of their courage and goodness. We are not worthy to follow them. Yet, from eternity, as from that towering North American wilderness, comes a gentle reply, echoing down the centuries: 'Serve God in the charity and love which expels fear; he does not turn his eyes upon our merits, but upon his own goodness.'

May we, with St. Isaac Jogues, offer our lives and our sufferings to Christ the High Priest, and may we too, at the end of our pilgrimage, receive back innumerable spiritual children in the loveliness of heavenly mansions. Indeed, “Not without reason does he ask our life, who has given up his own for us.” Let us remain steadfast in our Faith and in the Church. What we sow in tears, we reap in eternal joy. In utter humility, in strength and sweetness, relying entirely on the Providence of God, who alone gives the gift of final perseverance, we may make our own the words of the courageous Chieftain: “I tell you that I hold to the tradition of the Fathers; I accept it, and I shall keep it until the world shall burn and come to an end.”

The Mass made the missionary a martyr.

What might it make you?

Select Bibliography:

The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791. Ed. Reuben Gold Thwaites. Burrows Brothers, 1898.

The Martyrs of the United States of America: Preliminary Studies. Mack Printing, 1957.

Moreshead, Joseph. “The Life of Fr. Sebastian Rale, SJ.”

O’Brien, John A. Saints of the American Wilderness. Sophia, 2004.

Parkman, Francis. The Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth Century, Part II.

O’Brien, Saints of the American Wilderness, 45.

Despite innumerable adversities, the Jesuits were astute observers of all they witnessed, and were also remarkably fair and balanced in their assessment of native life, in an age in which most Europeans viewed Native Americans with implacable disdain and fear. The sons of St. Ignatius saw further. Above the dangerous horizon and the valley of tears, they saw glorious Heaven, their eyes forever lifted with the Host, Godward and upward.

O’Brien, Saints of the American Wilderness, ix.

Tadoussac Mission, one of the oldest in Canada, is about 215 kilometers north of Quebec City.

The Jesuit Relations, Vol. 21.

The Nbisiing Anishinaabeg, a subgroup of the Ojibwe and Algonquin peoples.

The Jesuit Relations, Vol. 21.

Conversions were not at once numerous, but this was due in part to the insistence of the Jesuits on thoroughly teaching and examining their catechumens before administering the Sacrament of Baptism, unless death was imminent. They were well aware of the heroism and sanctity which would be demanded of the native converts if they were to persevere in the faith amid pressure from family and tribe to return to their former idolatry.

The Jesuit Relations, Vol. 23.

Dr. Kwasniewski has written a fascinating article about the strange history of this carol and its popular but unfortunate rendering in English at the hands of Jesse Middleton in 1926.

Marie-Madeleine de Chauvigny de la Peltrie was the remarkable companion and benefactress of St. Marie de l’Incarnation, the holy foundress of the Ursulines of Quebec. Another essay would be required to do justice to these heroic Missionary mothers.

The Jesuit Relations, Vol. 27.

The Jesuit Relations, Vol. 29.

The legacy of the fiery Jesuit Fr. Sébastien Râle remains highly controversial today. A fierce defender of his beloved Abenaki, he encouraged armed resistance to the English encroachments on their land. Joseph Moreshead has written a thorough and inspiring apologia for Father Râle, who was killed by the English in the Norridgewock Massacre of 1724. The Abenaki, who dearly loved him, buried him under the charred remains of his altar. Louise Ketchum Hunt, a descendant of survivors of the Massacre, recounts how for generations, the Wabanaki cherished the Faith and kept Fr. Râle’s memory in oral tradition, so thoroughly had he imbued in them his own ardent devotion to Christ, the Sacraments, and the Catholic Church.

“Letter from Father Sebastien Rasles, Missionary of the Society of Jesus in New France, to Monsieur his Brother,” friendsoffatherrale.org | primary-resources.

Ibid.

Ibid.; also, The Jesuit Relations, Vol. 67. Father Râle explains to his brother that “what we understand by the word Christianity is known among [them] only by the name of Prayer.” Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi, Lex Vivendi.

O’Brien, Saints of the American Wilderness, 51.

The Jesuit Relations, Vol. 31.

O’Brien, Saints of the American Wilderness, 77.

O’Brien, Saints of the American Wilderness, 86.

The Jesuit Relations, Vol. 31.

For the past several years I have served with the Company of St. Rene Goupil on the annual Pilgrimage for Restoration. It isn't too late - even today, Thursday, early afternoon - to look them up and sign up to take the pilgrim road from Lac du Saint Sacrement (,Lake George) to Ossernenon (Auriesville) and stand on the very ground where Saint Rene Goupil, Saint Isaac Jogues, and Saint Jean de Lalande split their blood for Christ!

God bless you for making this public. Will share this on other social media platforms as well. 🙏🏼