What I’ve Been Reading Lately…

Northbourne on going south; Guadalupe, Pickstock, Orbán, Alcuin, Junípero Serra, Ludolph, Augustine, and Tolkien; Office, Lectio, and Rosary

As I’m spending this week out of town, visiting my daughter, my son, my daughter-in-law, and their baby girl (my first grandchild!), it’s not realistic for me to attempt a weekly roundup, not least because I haven’t been able to read as voraciously online as I usually do. If you like the roundup at T&S, don’t worry, it’ll be back again next week!

For today, I thought I would simply share with you the new books I’m reading at the moment, or rather, the ones I think are especially worth bringing to your attention. Constraints of time prevent me from writing proper reviews, so this is more in the manner of a series of book notices, with no ranking implied in the order in which I present them.

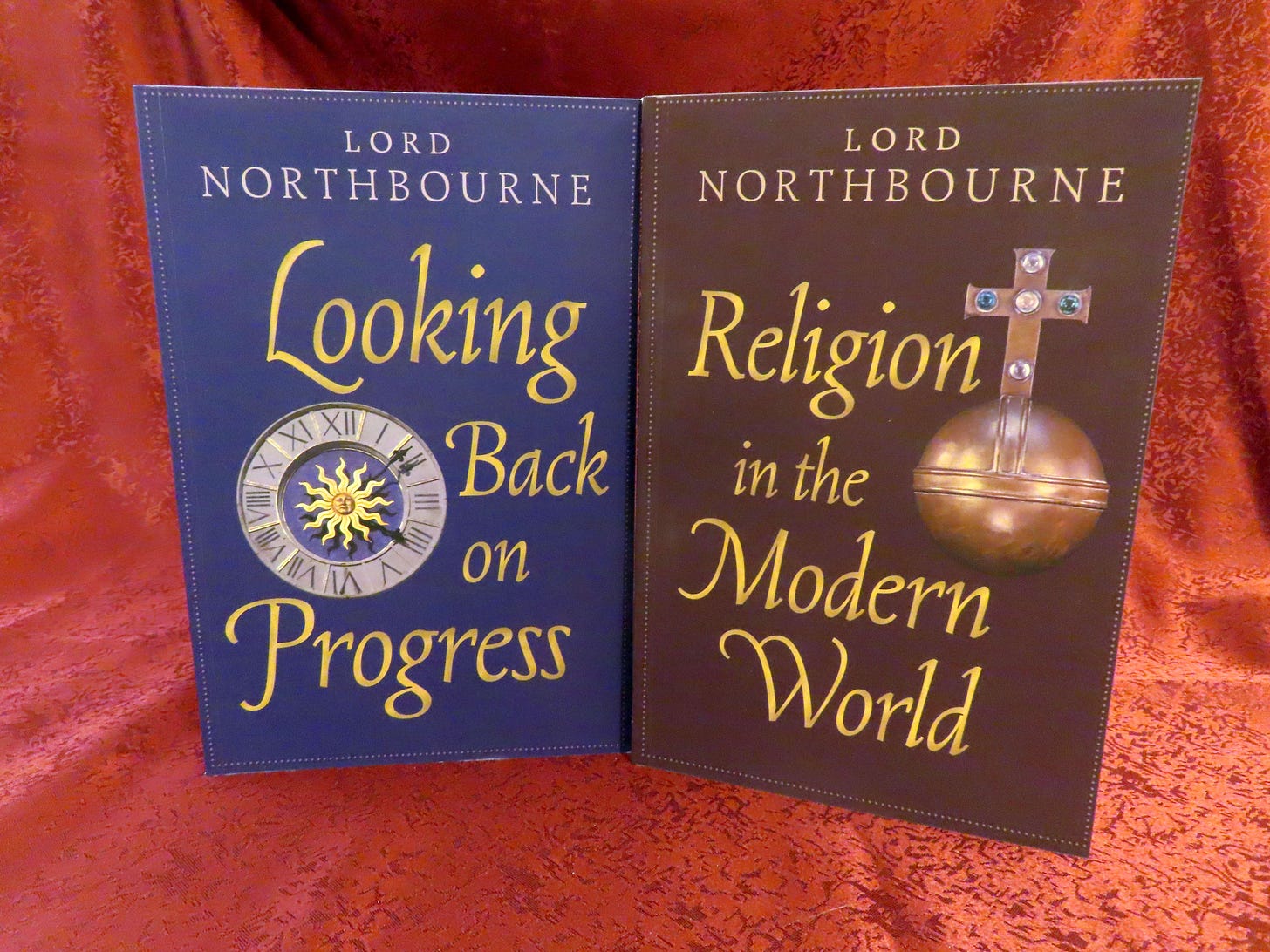

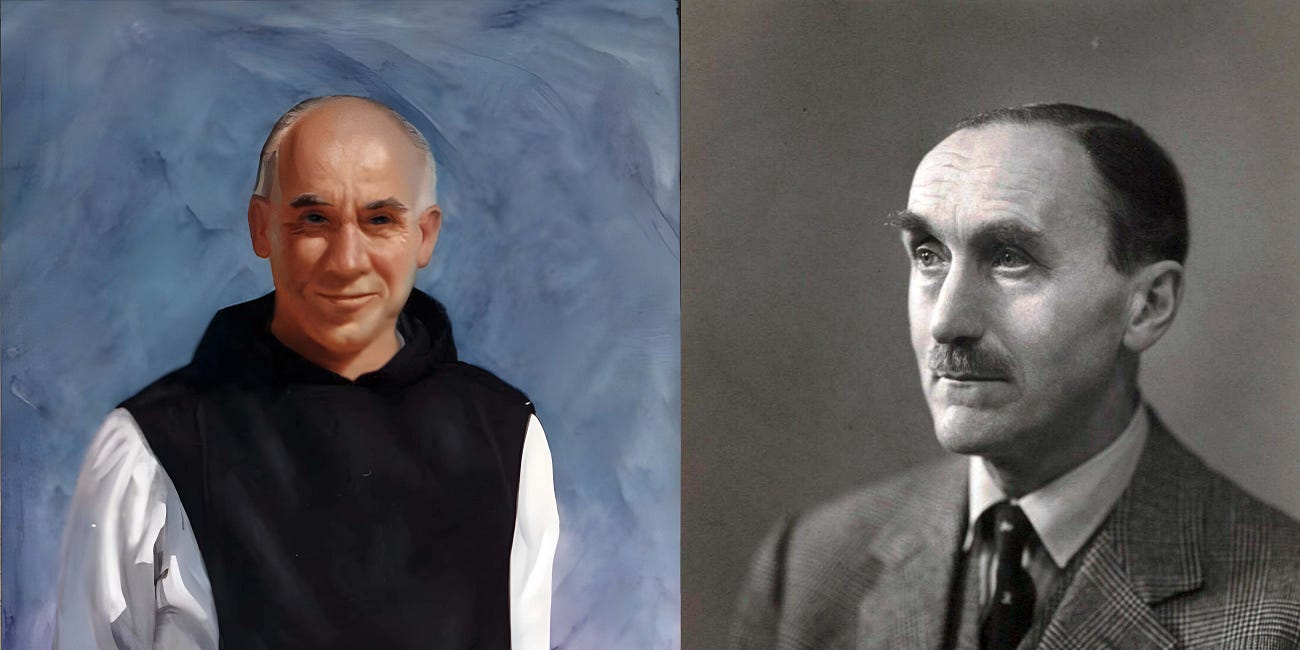

Angelico Press has done us a great service (one of thousands!) by bringing back into print two short but potent works by the Anglican Perennialist Lord Northbourne, whose name may be familiar to you from Sebastian Morello’s recent article on the correspondence that gentleman conducted with Thomas Merton:

Lord Northbourne Confronts Thomas Merton on Vatican II

Walter Ernest Christopher James, 4th Baron Northbourne (1896–1982), was a fascinating thinker whom I’ve discovered only recently. Besides being an English aristocrat and hereditary landowner of much working countryside, he was a religious thinker and the first translator into English of the works of René Guénon and Frithjof Schuon, perennialist philosophers who eventually became Muslim Sufis.

As it happens, Lord Northbourne was the translator of René Guénon’s major work The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times, a book whose title I played on in the series I published here about the Novus Ordo (all four parts are linked in this final part):

The Reign of Novelty and the Sins of the Times: Why the Novus Ordo Is Solely Modern in Content (Part 4 - Conclusion)

In the last part, we refuted the notion that the Novus Ordo is “more ancient” or that it resembles early Christian liturgies; on the contrary, its (1) con…

If you’re looking for thoughtful reflections steeped in the Western wisdom tradition, Northbourne is worth adding to your list.

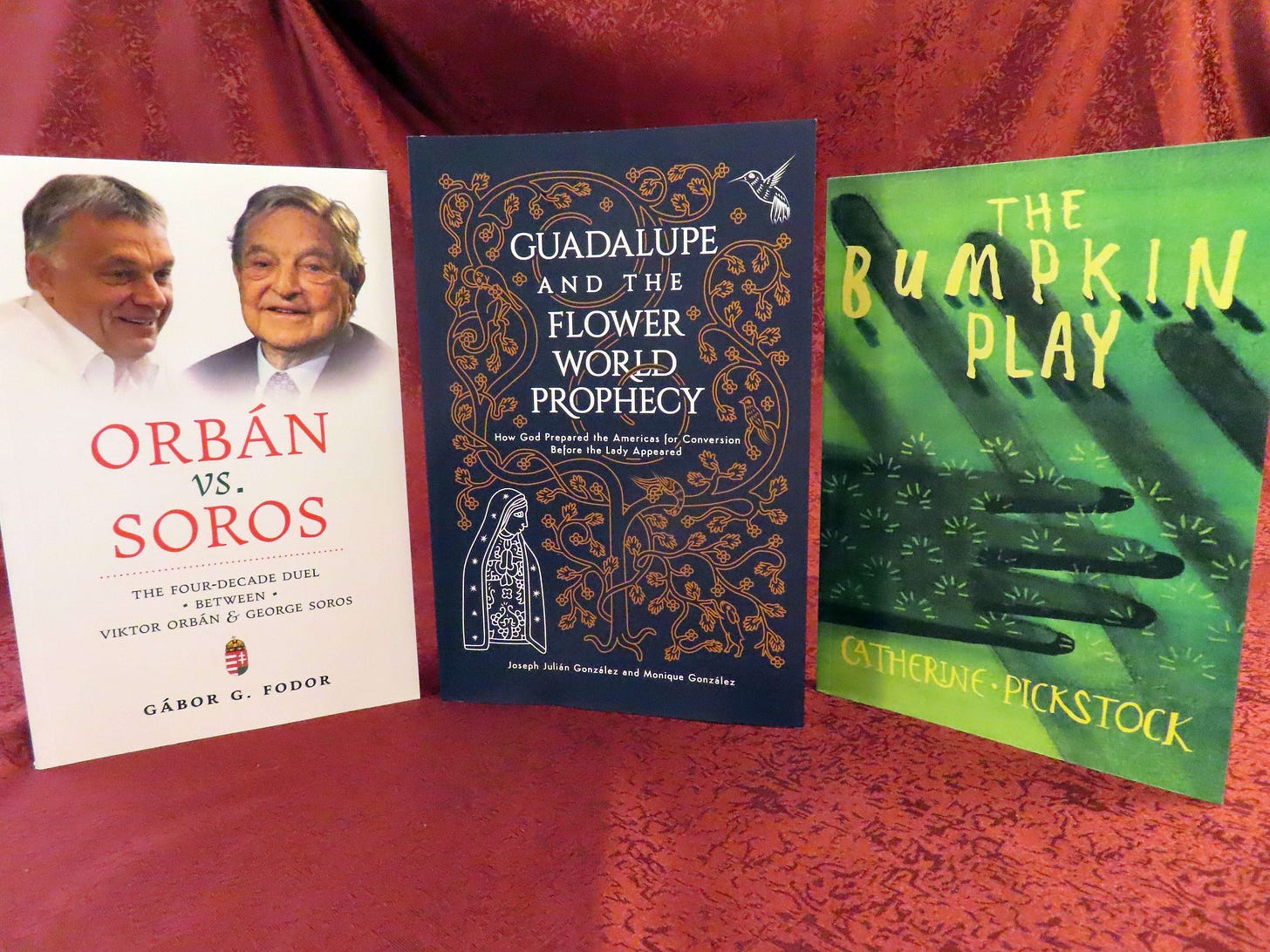

Speaking of wisdom traditions, I have to say that Guadalupe and the Flower World Prophecy (Sophia Institute Press) has been an absolutely fascinating read. I can’t sum it up better than the publisher has done:

At the beginning of the famous encounter between St. Juan Diego and Our Lady of Guadalupe, as Diego ascends Tepeyac Hill, he is suddenly surrounded by beautiful music and wondrous sights, whereupon he asks himself, “Where am I? Could this be the place that our ancestors spoke of — the Flower World Paradise in the land of heaven?”

With these words, St. Juan Diego ties his encounter to an ancient indigenous belief system — a spiritual floral domain named “Flower World.” This startling history was recently uncovered by anthropologists and archaeologists. In referencing this flowery paradise, Juan Diego opens up a fascinating link dating back to the very cradle of American civilization.

Flower World permeated Pan-Mesoamerican culture from its inception, accentuating ancient American man’s yearning for a paradisiacal afterlife saturated with music and beauty. This is expressively reflected in flower song poems of the era, whose primary metaphor is that of a singer calling down flowers from heaven to gather in his tilma so he might share them with lords and princes.

This exciting new interpretation of American prehistory lays the groundwork for a prophetical reinterpretation of the Guadalupe narrative. Joseph and Monique Gonzalez shed new light on the astounding events of Our Lady’s appearance at Tepeyac in December 1531. They present a fresh explanation of the roughly ten million indigenous conversions that occurred after the Blessed Mother’s appearance — considered the single largest Christian conversion event in history.

Painstakingly tracing the latest archaeological interpretations of Flower World along with the philosophical ramifications behind the flower songs, the Gonzalezes make a compelling case for the Guadalupe apparition’s being the culmination of thousands of years of evangelical preparation of the people of the Americas.

This is not a light read, as it’s an extremely detailed work, digging deeply into Mesoamerican sources and scholarship. (I also feel it could have used a bit more copy-editing.) But the authors’ case is watertight; at the end of the day, one is convinced that the Holy Spirit was at work to prepare these civilizations to receive the Gospel in a very specific way, using the indigenous religious imagery that resonated with them. In spite of the many errors of their paganism, they had glimpsed something about the nature of the afterlife that gave Our Lady the perfect opportunity for intervention on a massive scale.

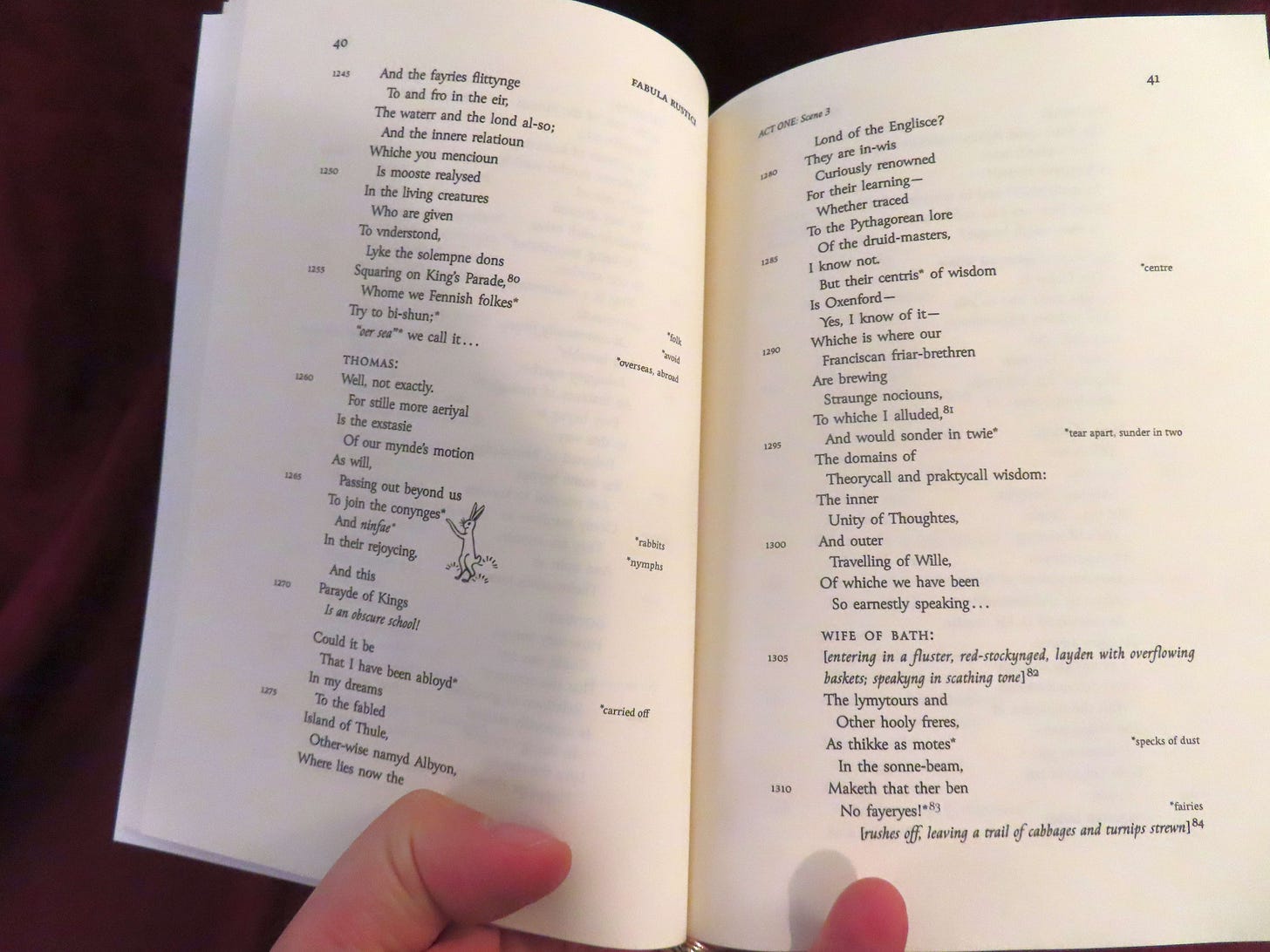

Similarly intriguing, and whimsical withal, is a most unusual work by Catherine Pickstock: Fabula Rustici, or, THE BUMPKIN PLAY (Angelico), in which a literary conceit — that we are reading a lost medieval drama, now faithfully restored by a modern scholar — is carried out to utter perfection, down to the last jot and tittle.

What is truth and what is fiction? In this optimistic play, of uncertain origin, Goobet enquires into the nature of truth, encountering a range of philosophical characters who happen to be passing by the village green. The play is upbuilding for Goobet, an unlettered bumpkin, but also for us in our own day. It turns out that a “walkynge-trewth” is one that is lived and performed in real time, rather than statically mirrored, which means that our work of reading is implicated in the general afflatus with which the play concludes. In this troubling epoch of “slydyrnesse” and “(f)flottys-fact,” in which we stumble in the shadow of blind gods, Goobet’s guileless uncovering of the vanity of human claims to certainty, at the same time as revealing a higher or vertical truth which we cannot but inhabit, is an encouragement to us all.

To be more precise: familiar themes of Radical Orthodoxy (e.g., three cheers for Aquinas on esse; please show Scotus the door!) are woven throughout, but in a frolicsome and ironic manner, with delicious parodies of academia. Definitely a niche work, but for those who savor that niche, nonpareil.

A couple of pages from the interior to whet the appetite:

Remote from hoary pagan wisdom and metaphysical parody alike is Gábor G. Fodor’s Orbán vs. Soros: The Four-Decade Duel Between Viktor Orbán & George Soros (again, Angelico). As mentioned in last week’s roundup, I follow the situation in Europe closely; it causes alternating grief and glimmers of hope depending on whether I am looking at the societal and cultural meltdown fomented by centuries of ever-accelerating liberalism, or turning my gaze to increasing signs of resistance from both Catholics and secular “rightist” forces.

But the phrases I have just used could be summed up more pithily as: Soros vs. Orbán.

As Fodor shows in this compact but well-researched study, these two Hungarians, who began as associates and developed into antagonists, represent two diametrically opposed worldviews for Europe and for the West in general:

Fodor presents the Orbán–Soros duel as an ultimately metaphysical struggle between two eternal principles: a horizontal universalism (Soros) that sees all boundaries as subversive and opposed to human freedom, and a vertical particularism (Orbán) rooted in form, limitation, and tradition while descending from and being presided over by the metaphysical order, and the God Who created it. These are the poles between which human social life oscillates in the post-Soviet world, expressed as a liberal globalist hegemony promoting and acting out of a unipolar world, and a multipolar world of discrete nations, cultures, and histories. Orbán vs. Soros swiftly cuts through the fog of present history to present a vivid picture of the forces impinging on all of us, and the inescapable choices we confront.

Language like the foregoing is enough to make one think of the need for saints — and the likelihood of more martyrs.

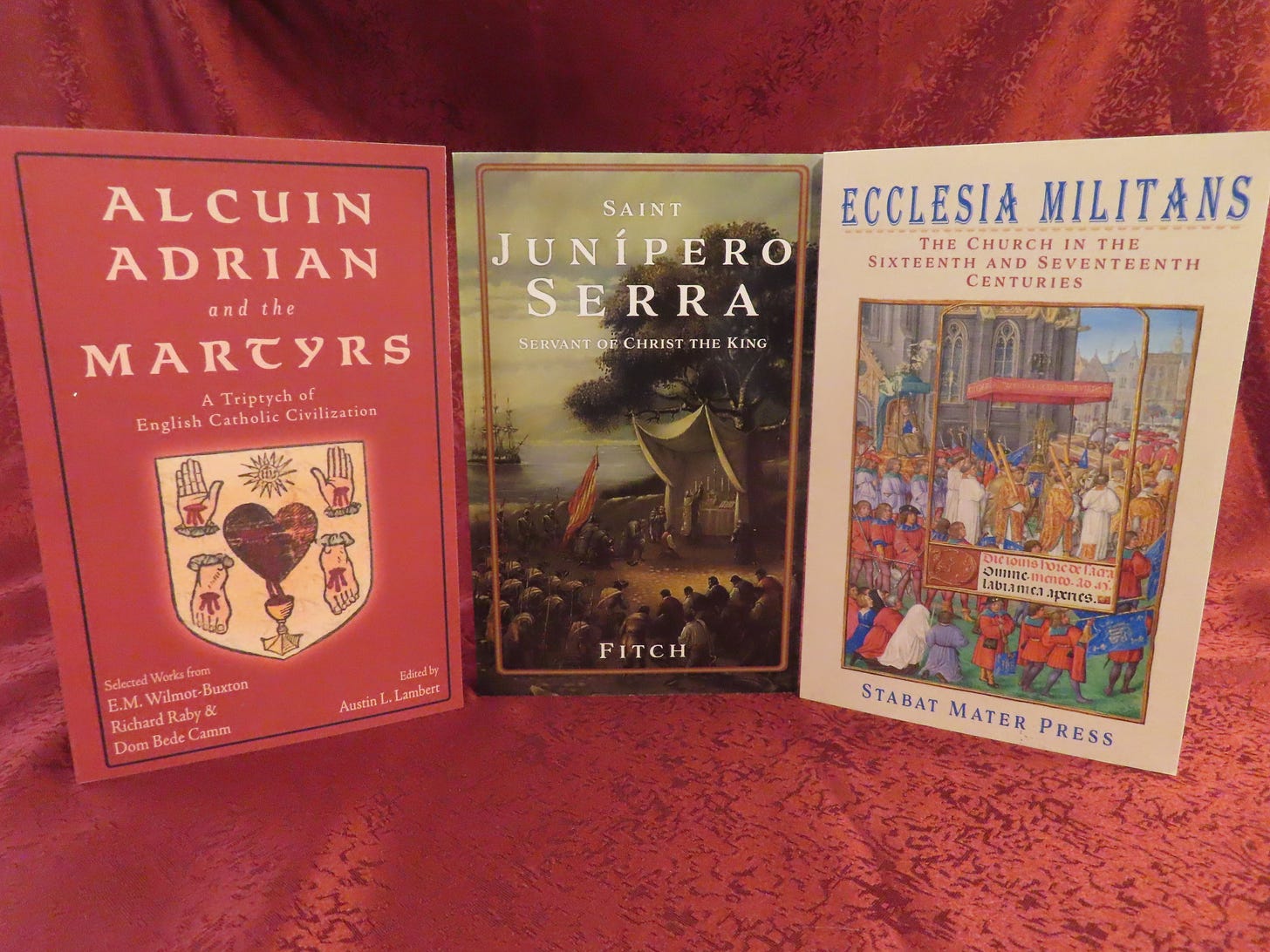

I welcome on to the scene a new Catholic publisher, Stabat Mater Press, with whose publisher Austin Lee Lambert I have exchanged some edifying letters. His literary mining has discovered some old gems, which he is repackaging in newly typeset editions, rescuing them from the indignity of OOPishness (out-of-printness).

Thus, the book Alcuin, Adrian, and the Martyrs: A Triptych of English Catholic Civilization “gathers three portraits from that vanished civilization: Alcuin of York, the Benedictine scholar who helped shape the mind of Christendom; Pope Adrian IV, the only Englishman to ascend the Chair of Peter; and the Elizabethan martyrs, whose blood consecrated a land already in ruin. All are men formed by a world in which the Faith governed law, language, and kingship. With selections from E.M. Wilmot-Buxton, Richard Raby, and Dom Bede Camm, Alcuin, Adrian and the Martyrs offers a triptych of English Catholic order: its mind, its power, and its suffering.”

Ecclesia Militans: The Church in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries “presents a clear and faithful Catholic account of the great changes that swept through the Church and the world during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Beginning with the early causes of the Protestant revolt, it traces the rise of Lutheranism, the spread of heresy in Germany, France, and the Netherlands, and the long wars that followed across the Christian world. The chapters follow the Church’s firm and supernatural response: the Council of Trent, the reform of religious life, the founding of seminaries, and the tireless efforts of faithful clergy to restore order, catechize the people, and guard the deposit of faith. Special attention is given to the rise of missionary work across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, and to the heroic fidelity of Catholics in England, Ireland, and Scotland, who remained loyal to the Church through persecution, exile, and civil war.”

Saint Junípero Serra: A Servant of Christ the King offers “a thorough and historically grounded account of Fray Junípero Serra, the Franciscan missionary best known for founding the California missions. Drawing on early sources, Fitch traces Serra’s life from his early formation in Majorca through his missionary work in New Spain and the Sierra Gorda, up to his role in establishing the Church’s presence along the Pacific coast. Fitch avoids romantic embellishment, offering instead a plain and faithful account of Serra’s trials, travels, and tireless efforts to bring the Catholic faith to indigenous peoples. His physical endurance, deep piety, and missionary discipline are treated with the respect due to a man now canonized a saint, while the surrounding political and ecclesial context is sketched with care.”

Welcome to the guild of publishers, Stabat Mater Press — you’ve made a bold entry (sixteen titles and counting!), we are happy to see you, and we wish you much success.

Meanwhile, nothing is going to improve — in ourselves, in the Church, in society as a whole — unless and until we are praying, and, I would add, doing so not only spontaneously and privately (which we can never bypass), but also with orderly, objective prayer forms that pre-exist us and bring us into fellowship with other Catholics offering the same praises and petitions. Our tradition is fertile with such prayer forms but certainly the Divine Office has a privileged place among them.

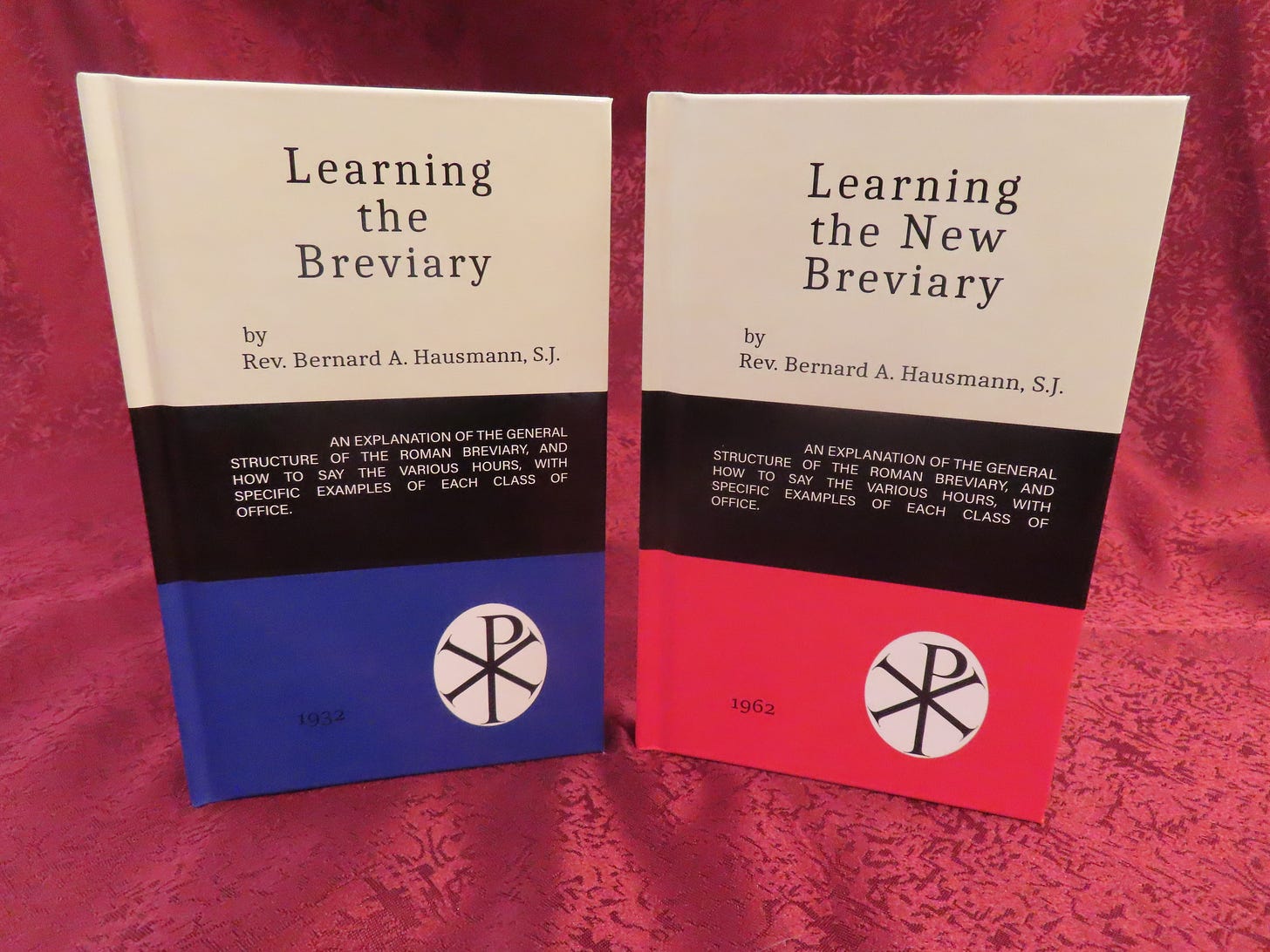

I was therefore quite chuffed when I discovered, not long ago, that a classic work on how to pray the Roman Breviary (no easy task to master without guidance!) has been republished, in two editions, in both hardcover and paperback. This is Fr. Bernard A. Hausmann’s Learning the Breviary (for pre-55) and Learning the New Breviary (for the 1962). Your go-to guide for getting fully up to speed with the Pius X office.

(Maybe someday there will come a reprint of a pre-Pius X office along with a Hausmann-style guide to it, but there are so many practical obstacles to this happening that I always advice people not to hold their breath and just to take up the next best thing available. Better to plant and water some flowers than to wait for a new orchard to arrive. Another good option for the Divine Office is the Benedictine monastic office. If you want it in Latin and English, you can get the 1962 version of the day offices here. If you can manage Latin alone, then you can get the complete monastic office in a beautiful new two-volume set from Dom Alcuin Reid’s monastery.)

Arouca Press, run by my friend Alex Barbas, publishes marvelous books. Alex is unafraid to bring out undeservedly neglected older works regardless of their length or difficulty, and regardless of how many will line up to purchase them — simply because these books deserve to be in print. I admire that spirit!

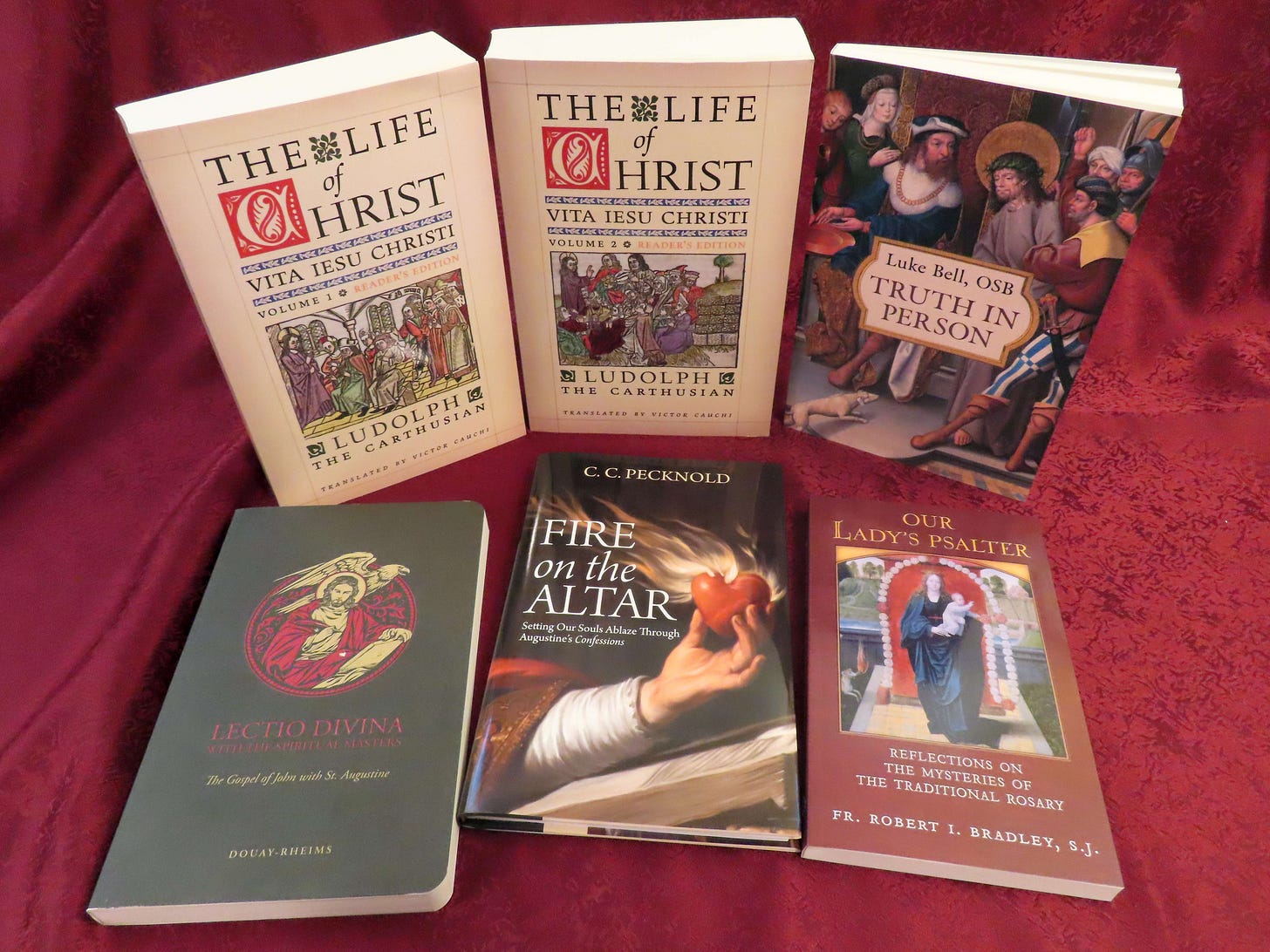

An example would be Ludolph the Carthusian’s The Life of Christ (Vita Jesu Christi), in two volumes. “The chequered life of Ludolph the Carthusian (c. 1295–1378) found its spiritual contentment in the writing of his colossal work on the Vita Jesu Christi in Latin. The book on the life of Christ occupied some forty years of Ludolph’s life in a charterhouse in Mainz. It has been styled as a summa evangelica, containing dogmatic and moral meditations, spiritual instructions and prayers.”

Regarding Fr. Luke Bell, OSB’s latest (with Angelico — it’s becoming a refrain), Truth in Person, I will confess up front that I have not yet broached this book. However, I’ve greatly enjoyed every book by Fr. Bell that I’ve read so far, and the table of contents alone in this one makes me impatient until I get a chance to sit down with it and savor his delicious combination of theology and literature. Alliteration is one of my favorite devices, so right away Fr. Bell caught my attention:

Publisher’s description:

In a world increasingly dependent upon technology for information and procedures, a longing for human persons—once ubiquitous, now often hidden behind screens—grows deeper and more urgent with each passing day. This book argues that it is only through persons that we can approach truth, which transcends what can be computed in rational analysis. Drawing upon science, sacred scripture, philosophy and literature, it shows us how the hunger for such truth in our troubled world can be fed by Christ, the Bread of Life, the Truth in Person. Speaking to the growing truth-instinct of the young, it deconstructs the algorithmic view of creation in order to kneel before this Truth, witnessing to its emergence in personal dialogue among all persons, in nature seen poetically as a mother and above all in the truthful life fostered by friendship and fraternity, which culminates in sharing the blissful knowing and loving of the persons of the Holy Trinity.

Chad Pecknold’s Fire on the Altar: Setting Our Souls Ablaze through St. Augustine’s Confessions, is the latest in that peculiar genre of Augustinian literature, namely, “The KEY to the unity of the Confessions.” What is the central motif, the unifying theme, the image or idea that prevails from start to finish? As Michael Foley said to me this past summer on his porch, Augustine is such a rich and complex thinker, and the Confessions so extraordinarily dense and artful a text, that you can have a dozen “master-key” explanations and all of them can be true. There’s no need to be exclusive about it.

Thus, Pecknold has certainly put his finger on a unifying theme, namely, “that the entire Confessions coheres around the Sacrifice of the Mass, revealing that it is only by union with the fire of divine charity on the Church’s high altar that we can make a sacrifice acceptable to God.” Here we have the Catholic Augustine presenting a liturgical and Eucharistic interpretation of human life, experience, and salvation.

(Although this book is available only for pre-order, the St. Paul Center very kindly sent me the copy you see in the picture ahead of time, so I could begin delving into it.)

If you are the kind of person who enjoys journaling, TAN Books has made lectio divina easier and more profitable by creating a new series called Lectio Divina with the Spiritual Masters. The first two volumes are The Gospel of John with St. Augustine (pictured above) and The Gospel of Matthew with St. John Chrysostom. The format is like this, following the four classic stages of lectio, meditatio, oratio, and contemplatio, with space for notes:

In the category of meditation could also be placed Our Lady’s Psalter: Reflections on the Mysteries of the Traditional Rosary by Fr. Robert Bradley (Angelico).

One day in the early 1990s, while praying the Joyful Mysteries of the Rosary on his knees in front of the Tabernacle, Fr. Bradley heard the Holy Spirit telling him: “Write this down!” He was given a meditation about the Annunciation. Thus was born a 10-year journey of inspired meditations on every bead of the Traditional Rosary. From then on, not knowing when the Holy Spirit would give him another meditation, Father brought a yellow legal pad with him for his Rosaries by the Tabernacle. He said the Holy Spirit slowly gave the meditations to him, one at a time, during prayer before the Blessed Sacrament, becoming what he called “my love letter to the Blessed Mother.” Of the many books written about the Traditional Holy Rosary, these meditations are the first to focus on all 150 beads. They are presented here to help lead souls to a greater love for Immaculate Mary and her Son Jesus as we journey to our eternal life in Heaven.

I can only say that the rapturous endorsements from Kathleen Beckman, Robert Fastiggi, Fr. Donald Calloway, Fr. Jeffrey Kirby, and Michael Foley are by no means exaggerated.

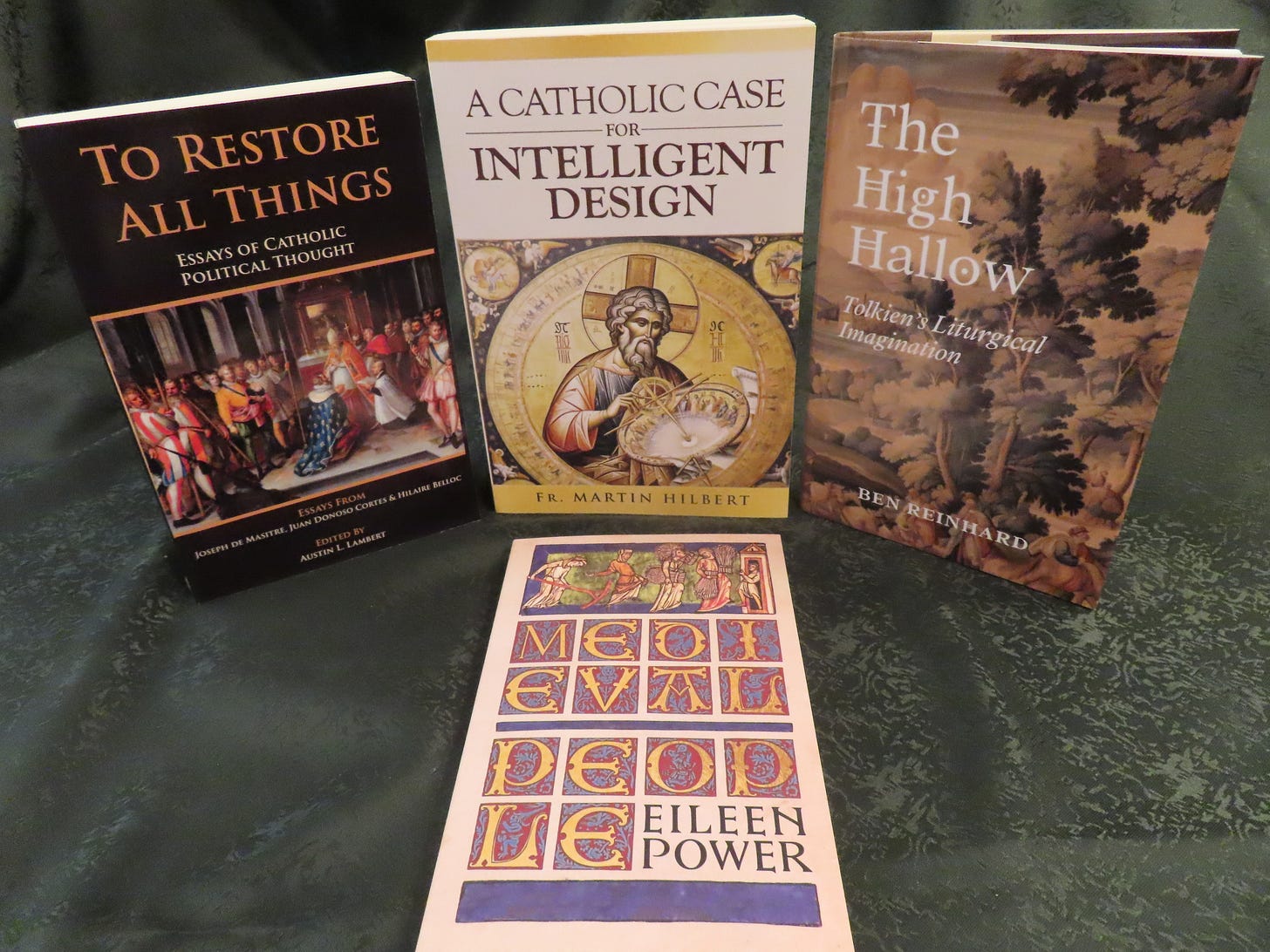

In a last and even more miscellaneous grouping, we see:

To Restore All Things: Essays of Catholic Political Thought (Stabat Mater Press)

In this collection of three classic essays, towering figures of Catholic political thought confront the spiritual and political collapse of modern liberal society. Joseph de Maistre exposes the myth of rationalist constitutionalism, arguing that true authority is born not from abstract theory but divine providence and historical continuity. Juan Donoso Cortés traces the theological decay that leads from liberal compromise to revolutionary violence, warning that societies which reject the Cross will not escape the sword. Hilaire Belloc, writing in the heart of industrial England, shows how both capitalism and socialism converge upon the same destination: the restoration of servitude under a new economic guise.

Fr. Martin Hilbert, A Catholic Case for Intelligent Design (Discovery Institute)

A faithful catechist in Fr. Martin Hilbert’s parish came to see him. “Father Martin,” she said, “I have been teaching children about Adam and Eve, just as the Catechism tells us. But we can’t be expected to believe that, can we? What is the real story?” Her question was the catalyst for A Catholic Case for Intelligent Design. In taut, accessible prose, Fr. Hilbert draws upon his broad learning in science, philosophy, history, and theology to show that modern evolutionary theory, including theistic evolution, faces a rising wave of disconfirming evidence. Meanwhile, the evidence for both intelligent design and a first human couple, Adam and Eve, is stronger than ever. What about the problem of suffering, disease, and death in a world created by a wise and good Creator? Fr. Hilbert tackles that issue as well, and explains why the theory of intelligent design, rightly understood, harmonizes perfectly with the Catholic theological tradition.

Eileen Power, Medieval People (Angelico)

Too little intimate history has been written of common people in the Middle Ages. Most “comprehensive” works pass them by in favor of tales of monarchs and warriors. Yet if we truly wish to form an accurate understanding of how life was during a certain period, it is to the lives of ordinary people that we should first direct out attention. It is precisely this strategy that Eileen Power employs in Medieval People. In this refreshingly insightful collection of lives untouched by fame, Power guides the reader through the everyday activities of merchants, travelers, peasants, and monastics, painting a vivid picture of medieval life through their personal stories. Though of course meticulously researched—drawing upon journals, letters, court documents, wills, and first-hand accounts—Power’s lives are far from the stuffily academic. She gives her characters room in a way that makes comfortable space for the reader to walk alongside them, sharing their daily activities, their wants and cares, trials and triumphs. Both highly enjoyable and informative, Medieval People is sure to appeal to students, teachers, and all those with a particular interest in medieval history.

Readers, be aware: Powers goes about her task with patient thoroughness, in no hurry to race through her “case studies” of ordinary medieval folk. So, if the idea of reading snippets from medieval court documents makes your eyes glaze over, you might give this a pass; but if you want a granular look at how the lowly folk lived a thousand years ago, this book will not disappoint.

Ben Reinhard, The High Hallow: Tolkien’s Liturgical Imagination (Emmaus Road)

Someone had to write this book. I’m relieved that the right person wrote it. Reinhard handles his theme superbly, with a confidence mastery of the enormous corpus of Tolkien’s work, and with remarkable brevity — nowadays it seems like a book of this sort rarely checks in under 400 pages, yet Reinhard does it in 184.

He is not afraid to mention that Tolkien was deeply disturbed by the liturgical reform that took place toward the end of his life, but he prefers to stay focused on the positive elements the author derived from the (preconciliar) liturgy he loved so much. I would only add that anyone who appreciates Tolkien will not only appreciate him more after Reinhard’s work, but will be given still further reasons to seethe with indignation at the destruction wrought on the greatest work of art ever known to mankind, that is, the traditional Roman Rite — since so much of what inspired Tolkien from the liturgy has either been ripped right out of it like a conquered victim’s heart torn out by a priest placating the angry god Modernity, or has been stifled in practice by decades of the “Fr. Randy Show” at the local parish.

If there is to be another Tolkien someday, I am convinced he will rise from within the traditionalist milieu. It could not be otherwise.

May a pope someday rise from the same milieu. Stranger things have happened, and the age of miracles is not yet over.

Don’t ever stop reading good books, it’s the difference (well, one of the differences) between merely living and living well.

Medieval People by Eileen Power seems like something I've been searching for :)

Actually, the pre-Pius X Office in English, including the Rubrics, can be found here: https://archive.org/details/bwb_S0-AUM-033_1/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater; this is the first volume. I actually find the pre-Pius X rubrics far superior, and Pius X rubrics unfortunately and needlessly complicated at times. Just need a bit more cleanup of the calendar, and demotion of very recent saints (around 1600s) to semidoubles or simples. Not feasible for the moment, but I hope that point will be reached.