Why We Should Follow the Traditional Catholic Numbering of the Psalms

The use of the Masoretic numbering betrays a misguided interreligious-ecumenical priority that dishonors the unanimous tradition of Greek & Latin Christendom AND falls foul of Hebrew tradition

The Bible was not divided into chapters until the 13th century, and verses came along in the 16th century. There are obvious benefits to having numbers for chapter and verses, especially for scholars; however, it must be admitted that it leads to a cluttered appearance on the page. As some have pointed out, when you open a typical modern Bible that is printed as single volume, the appearance is busy, not to say daunting: two columns of fairly small and dense text, strewn with numbers and footnotes. It is hardly a “reader-friendly” experience.

That is why I much prefer a “reader’s Bible” for devotional purposes. I use the Bibliotheca Bible, which is distributed into five hardcovers, printed in one column with a comfortable font size, generous margins, and ribbons — and best of all, no chapter or verse numbers. It’s a “clean” text that enables me to concentrate 100% on what is being said. If I need to find out the numbers, I can look up a verse in two seconds online. I’ve written more elsewhere about the question of different translations and editions, and the benefits thereof.

Here, I would like to talk about the book of Psalms. Different from the other books that were not divided up into chapters until much later, the psalter carefully separates the poems of which it consists, often by the use of a title and some description (e.g., Ps 3:1 reads “The psalm of David when he fled from the face of his son Absalom,” and Ps 9:1, “Unto the end, for the hidden things of the Son. A psalm for David”). In St. Paul’s inaugural homily to the Jews of Pisidian Antioch we find the words: “This same [promise] God hath fulfilled to our children, raising up Jesus, as in the second psalm also is written: ‘Thou art my Son, this day have I begotten thee’” (Acts 13:33).

The psalm commentaries of Church Fathers plainly refer to psalms by number. Of the many examples that could be given, let it suffice to showcase this 9th-century codex with St. Augustine’s Enarrationes in Psalmos:

So far so good.

However, to the confusion of readers across the centuries, the Psalms come in two different numbering systems — and the use of one or the other bespeaks a worldview.

As Jacob Prahlow explains:

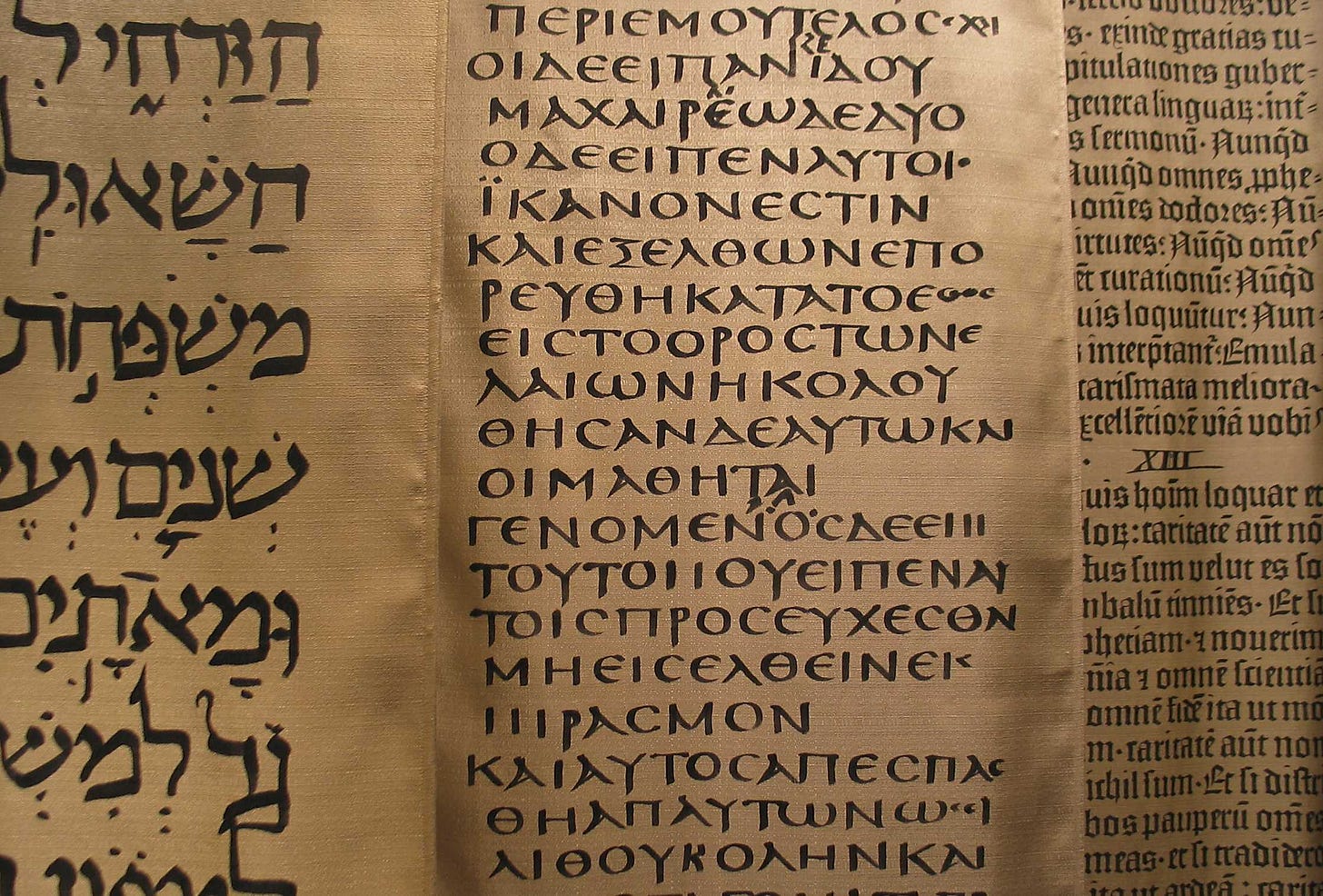

The Psalms were originally written in Hebrew and used by the People of Israel. A couple of centuries after the Babylonian Exile, however, fewer Jews living in Israel could read Hebrew, and even fewer Jews living outside of Palestine knew how to make sense of the language of their heritage. At least partially in response to this, a group of scholars translated the Hebrew Bible into the new lingua franca: Greek. This translation became known as the Septuagint, also called the LXX, because 70 (or 72) translators worked on the project. The LXX became the Bible for Jews living in the Greco-Roman Empire, was likely the Bible Jesus would have read, and most definitely served as the Bible for the writers of the New Testament (i.e., when the New Testament writers quote the Old Testament, they are quoting the Septuagint version, not the Hebrew).

Pause for a moment and let that soak in. The version of the Hebrew Scriptures that most Jews were reading at the time of Christ, the version all the writers of the New Testament quoted, was not the original Hebrew, but the Greek Septuagint. Prahlow continues:

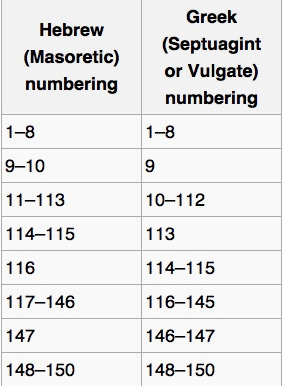

When the Book of Psalms was being translated from Hebrew into Greek, some of the Psalms were shuffled. For example, what were Psalms 9 and 10 in the Hebrew became Psalm 9 in the Greek. Both versions end up with the same number of Psalms (150), but (with a few exceptions) the numbering of the Psalms ended up being “off” by a single number. Thus, what many of us think of as Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my Shepherd…) was, for Christians following the LXX version of the Psalms, actually Psalm 22.

I quote this passage because it’s a great example of how careful one must be with trusting secondary sources. Prahlow speaks as if the Septuagint shuffled the psalms, but we will see in a moment a knock-down argument that it was later Jews who did so, with the Septuagint giving the better reading.

Here is a handy chart showing the effect of this difference:

Since, as we have seen, the psalm numbering of the Septuagint version dominated the early Church, it comes as no surprise that when St. Jerome prepared his translations of the psalter (yes, I used the plural on purpose: he made three separate translations!), he followed the Septuagint. And just as the Septuagint always remained the standard Bible of Byzantine Christianity, so did Jerome’s Vulgate become the standard Bible used throughout Western Christendom, without exception. That is why when Catholics finally prepared an English translation of Scripture, they based it on the Vulgate; and thus was born the famous Douay-Rheims Bible.

Hence, in any Bible used by orthodox Catholics, Eastern or Western, from apostolic times down to the Protestant Revolt, and again within the Catholic Church right to the Second Vatican Council, there is one and only one psalm numbering system used: that of the Septuagint and the Vulgate. In this system, certain famous numbers come immediately to mind. The Miserere is Psalm 50. When Jesus prayed on the cross, he recited Psalm 21, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me.” Psalm 118 is the great hymn in praise of the Law.

I shall call this the “received” numbering. All of the Fathers, Greek and Latin alike, all authors from the apostolic period through the scholastic, and then, Orthodox and Catholic authors from the sixteenth century on into the twentieth, use this numbering. Following the Rule of St. Benedict, all subsequent breviaries and office books refer to the psalms in this manner; thus, Psalm 50 is the Miserere said before Lauds; Psalm 118 is divided among the little hours; Psalm 66 begins Lauds and Psalm 62 is included in Lauds; Psalm 90 is prayed every night at Compline; Psalm 109 is the great messianic psalm that starts off Vespers; etc. These psalms quite simply are numbers 50, 62, 66, 90, 109, and 118 for Catholics, that is, for Christians who belong to the one and only Church Christ founded. (If one wished to include the Eastern Orthodox, the conclusion would be no different.1)

The Protestants, on the other hand, were the first to yield to a false antiquarianism by insisting on following the Hebrew Masoretic numbering of the Psalms, as if this were somehow “more authentic” than following the received Greco-Latin enumeration — on the assumption that the Jews must know best how their psalms are to be numbered! One suspects that ecumenism with Protestants and interreligious dialogue with Jews played an oversized role in this abandonment of the Catholic tradition for a foreign enumeration, although once again, the ecumenism strangely excluded the separated Eastern Christians, much closer to us in theology and liturgy, who to this day retain the Septuaginst psalm numbers.

False antiquarianism rears its ugly head at various points in Church history. The irony is that it very often turns out to be false: the consensus of scholars on “how things must have been back then” gets overturned by better research later, arriving at a different conclusion. To give some concrete examples, the view that early Christian worship had the minister facing the people has been proved false; the view that the Mass was said as a meal at a table and not as a sacrifice at an altar has been proved false; the view that the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus contains an early Roman anaphora, on the basis of which Eucharistic Prayer II was constructed, has been utterly overturned, to such an extent that it is now regarded as a pseudo-Roman, pseudo-Hippolytan, pseudo-anaphora (see here and here); the view that there were three readings in the ancient Roman rite, on the basis of which three were introduced for Sundays in the Novus Ordo, has also been proved false.

(For those who are interested, I discuss the phenomenon of antiquarianism in two articles online: “The Continual Spectre of False Antiquarianism” and “False Antiquarianism and Liturgical Reform.”)

And here is where the biggest surprise awaits us. As with all the earlier examples given of antiquarian views subsequently overturned by better scholarship, so too with the numbering of Psalms: it turns out that the evidence for the Septuagint numbering is far stronger on literary grounds than for the Masoretic numbering — so much so that the greatest scholar of Hebrew poetry in our times, Robert Alter, easily concludes that the Masoretic text must have become corrupted at some point (nor would this be surprising, since the Septuagint was finished well before the Masoretic text itself was finalized, and it is clear that the 70 translators had access to older Hebrew versions). In his introduction to the Psalms, Alter first makes a general observation:

There is abundant evidence that slips or blunders of this sort [viz., copyist errors] occurred again and again in the copying of the psalms, rendering some phrases or whole lines or even sequences of lines almost unintelligible. I don’t mean to exaggerate. Many psalms, including some of the most famous, such as the first, the twenty-third [i.e., the 22nd for us], and the last psalm in the collection, are beautifully transparent in the original from beginning to end, inspiring considerable confidence that there was no slip of the pen of the poet and the pens of the long line of scribes. But there are also many instances in which the meaning of the text as it stands is quite opaque, with no easy path of reconstruction back to what the poet might have originally written.

Then he comes to the point of chief interest to us:

Psalms 9 and 10 are a striking illustration of these textual problems. In the Septuagint, these appear as a single psalm. Internal evidence for their unity is the fact that together they form an alphabetic acrostic. Psalm 9 begins with the initial letters of the alphabet in proper order, though it lacks a line beginning with dalet, the fourth letter of the Hebrew alphabet. The acrostic vanishes in the last two verses of Psalm 9, reappears at the beginning of Psalm 10, only to vanish again, then resurfaces toward the end of the psalm, which has lines beginning respectively with the last four letters of the Hebrew alphabt (verses 12–17), though interspersed with lines that are not part of the acrostic pattern. This scrambling of the acrostic is accompanied by a slide into incoherence in 9:21 and 10:3–6. It is reasonable to infer that something happened here to the text more extensive than a scribal inadvertence. Perhaps a purportedly authoritative manuscript used by the line of scribes that led to the Masoretic Text was damaged — by moisture, fire, or otherwise. With bits missing and the continuity of the acrostic no longer in clear sight, some later editor may not have realized that these two segments of the text were the halves of a single poem. Moreover, at least in the four verses I have just cited, there may have been missing or illegible elements in the text, and a desperate scribe might have copied the incoherent fragments or, in an effort to make sense of them, created nonsense…2

Alter goes on to say that when the text is or appears to be corrupt,

I was especially encouraged to follow…divergences from the Masoretic Text when they were confirmed by one or more of the ancient translations [including the LXX!], or by the Qumran texts, or by variant Hebrew manuscripts.3

At the risk of slight repetition, I should like to quote Alter’s commentary when he reaches Psalm 9 itself, where he writes:

This psalm and the next one are a striking testimony to the scrambling in textual transmission that, unfortunately, a good many of the psalms have suffered. The Septuagint presents Psalms 9 and 10 as a single psalm, and there is formal evidence for the fact that it was originally one poem. Psalm 9 in the Hebrew begins as an alphabetic acrostic…. Then Psalm 10 begins with the next letter of the alphabet, lamed, after which the acrostic disappears, to surface near the end of the psalm with the last six letters of the alphabet…. Something along the following lines seems to have happened: at some early moment in the long history of its transmission, a single authoritative copy was damaged (by decay, moisture, fire, or whatever)…. [T]he editors, struggling with this imperfect text, no longer realized that it was an acrostic and broke it into two separate psalms.4

Looking back over what we have seen, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that it was only under the influence of Protestantism and ecumenism that Catholics more recently, surrendering an unbroken bimillennial tradition, chose to set up their Bibles and cite their Psalms with only the Hebrew/Protestant numbers. By doing this, we are giving up the most historically and theologically influential and normative numbering, in order to be, as far as I can tell, nicey-nicey, with-it, relevant, ecumenical and interreligious. If by now we have not learned our lesson about all the bad things that follow from sudden fashionable departures from tradition, I wonder if we ever shall.

“Is the numbering of the psalms a doctrinal issue?,” a skeptic might object.

No, it is not a doctrinal issue as such; but it is symptomatic of attitudes and mentalities that do have doctrinal origins and implications. I mentioned false antiquarianism earlier, the presence of which should be a red flag for a Catholic with sound principles. The use of the traditional numbering signifies a desire to stand solidly with the line of Providence that begins with the Septuagint, runs through the New Testament and all the Church Fathers and Doctors, and reaches down even to us who inherit this grand body of work. The use of the other numbering signifies a desire to go along with unfaithful traitors of the covenant and members of maimed ecclesial bodies with anti-Romanism at the basis of their humanly constructed creeds.

Given that the LXX/Vulgate numbering is altogether traditional for the entirety of the Christian world, East and West, with no competing alternative; given that Renaissance Humanists and the original Protestants, and later on the Vatican II ecumenists, shifted their numbering system on the basis of a theory of antiquarianism that the Church has rejected in Pius XII’s encyclical Mediator Dei; given that the particular textual decision on which the entire Masoretic numbering system rests, namely, the division of Psalm 9 into Psalms 9 and 10, is highly likely to be based on a later corrupted Hebrew text and that the LXX bears witness to an earlier and better tradition — I see no responsible course of action for any Catholic scholar but to refer to Psalms 9 through 147 by their traditional Christian numbers.

If writers would like to include the Hebrew/Protestant numbers as a courtesy to readers who do not share the Faith, they might include them in parentheses after the correct numbers, as one often sees in older books. In no circumstances, however, would it be theologically or textually defensible for Catholics to use exclusively the Hebrew/Protestant enumeration. This, at any rate, is what I have made a point of doing in all of my own books or in books that I’ve edited, and I would encourage other Catholic writers to do the same.

Thank you for reading, and may God bless you!

In his book Orthodox Eastern Church, Fr. Fortescue complains about some of his countrymen: “The LXX has always been the official version of the Byzantine Church, as the Vulgate is ours. Protestants, on the other hand, make quite a fetish of the Massora [viz., Masoretic]. But to print a Greek Bible without using the LXX is an almost incredible piece of arrogance and absurdity. Two Englishmen made this new version and thought they could do better than the LXX!” One wonders what Fortescue would have said about the period of the Second Vatican Council; I imagine his aptitude for withering satire might have been stretched to the limit.

Robert Alter, The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary, vol. 3: The Writings (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019), 24.

Alter, 25.

Alter, 40.

My good friend and NLM colleague Gregory DiPippo shared with me some counterpoints concerning my article on Psalm numbering. In a spirit of seeking the truth, I would like to share these here.

<< 1. First, St Jerome did not do three translations of the Psalter. He did two emendations, correcting a Latin text already in use on the basis of the Greek. One of these has been lost, the other is the one in the breviary. He then did a translation directly from Hebrew.

2. The story of the 70 translators from which comes the term Septuagint is universally regarded as an historically tenuous legend at best. But even if every word of the traditional version were true, it would still apply only to the Torah. The other books, including the Psalms, were translated rather later, and not as the result of a unitary project, but piecemeal, by different translators working with different approaches. It is generally thought that the Psalms were done in the 2nd century BC, roughly 120 years after the translation of the Torah.

3. It is universally acknowledged that the divisions of the psalter found in the Septuagint are not fully accurate either, and in terms of the numbers of mistakes, the Septuagint has more. It incorrectly joins two Psalms into Psalm 113 (In exitu and Non nobis), and incorrectly divides a Psalm into two (114 Dilexi and 115 Credidi). It then incorrectly divides another Psalm into two (146 and 147), which is how it gets back to the same number of psalms in toto as the Hebrew.

4. It is also universally recognized that both traditions, the LXX and the Masoretic, unite two originally separate Psalms into one (our 26, their 27), and split a psalm that was originally one into two (our 41 and 42, their 42 and 43). These divisions may very well reflect some kind of liturgical use now lost and unrecoverable to us, but this brings up another point. The idea that the Hebrew division of 9 into 9 and 10 is a corruption of the Masorah is certainly a likely explanation, to be sure, but it is also possible that it too reflects a now lost and unrecoverable liturgical use. >>

The Psalms and their ordering are such an integral part of Catholic life right down to the bones. The change in their numbering in the Bibles and the Breviaries was one of the things that changed the air we breathe as Catholics after Vatican II so to speak.