Boniface Luykx’s Critique of the Novus Ordo as Defective Ritual (Part 2 of 2)

“Tradition is the life of the Holy Spirit in the Church”

In part 1 of this two-part presentation, we lingered in Chapter 3 of Boniface Luykx’s A Wider View of Vatican II.

Chapter 4 turns to how Vatican II has been betrayed, in the archimandrite’s view. He says that, in addition to the postconciliar commissions that mostly worked in private, there were public figures — “theologians backed by magazines” — who “desired the Council to be, above all else, the instrument of a thorough alignment with secular culture” (121; as before, page numbers in parentheses refer to the aforementioned book).

More particularly:

The dissenters came to align themselves with a wholesale attack on Christian spirituality, which of course resulted in a loss of prayer and prayerful worship. They attacked the spirit of the Beatitudes and the Magnificat and, indeed, all the events in which God vertically breaks through man’s horizontal, self-centered behavior. (128)

He is not surprised that serious Catholics are drawn to the East:

Hundreds, possibly thousands, of prayerful, truth-seeking Catholics each year join the Orthodox Churches. For them this may be a blessing, because in the Orthodox Churches they will find what had been stolen from them but they so eagerly desired: beauty, reverence, and the sense of majesty. Others discover the Eastern Catholic Churches where they find the deep reverence and beauty of Orthodox worship while gratefully remaining in union with Rome. (130)

False Principles of Western Modernity

On p. 131, Fr. Luykx returns to what he calls, in a heading, “Erroneous Theological Foundations of the New Liturgy.” Having cited two examples—the wholesale replacement of Latin with “street language and free translations,” and the replacement of Gregorian chant with “cheap tunes”—he observes:

Behind these revolutionary exaggerations were hidden three typically Western but false principles: (1) the concept (à la Bugnini) of the superiority and normative value of modern Western man and his culture for all other cultures; (2) the inevitable and tyrannical law of constant change that some theologians applied to the liturgy, Church teaching, exegesis, and theology; and (3) the primacy of the horizontal. (131)

The first of these three false principles, which he connects directly with Bugnini, was thoroughly covered in our last article on Luykx. As to the second principle, we find a welcome affirmation of the blessing of unchangingness in traditional rites, which makes it possible to engage well with them:

The dissenters proclaimed that the only certainty we have is “how we feel in the midst of all these changes,” since to them man’s feelings are normative for truth and life. Theirs was a totally man-centered approach to life and hence, inevitably, to worship. They believed that worship should catch people’s attention by constant change, and be shaped by how people feel. Here the anthropological law of Jean Cazeneuve steps in. This law correctly observes that one of the fundamental requirements for good and true worship is its unchanged continuity, its familiarity. Worshippers need to know what to expect and should not be subjected to unprepared surprises. If this law is violated, worship will suffer, as will the spiritual life of the believers. (133)

The law of Cazeneuve rests on the deeper anthropological law of continuity and discontinuity. In all cultures, true worship, as an expression of the holy, lies essentially in discontinuity with the profane (meaning here the secular or unsanctified). That is why worshippers keenly feel the need that the priest dress in liturgical vestments and use dignified language and gestures. (134)

The profane is sanctified by sacramentalizing it: for example, bread becomes the Body of Christ, changed from the most usual profane thing into the highest divine Reality. By giving this divine dimension to the profane, worship is per se the creator of beauty. This explains why the inner tendency of the new liturgy — despite its claiming the opposite — is actually the destruction of the divine beauty which Holy Tradition had accumulated in the Church’s worship, and why cosmetic corrections cannot solve the new liturgy’s problem. (135)

The third erroneous principle—“that the first and real foundation of ‘good worship’ was its horizontal (i.e., man-oriented) dimension, and that its vertical (God-oriented) dimension was secondary” (135)—was thoroughly treated in the first of my Substack series on Luykx, so we may pass it by here. Fr. Luykx is strongly committed to verticalism:

The liturgy’s aim is not primarily the horizontal “gathering of people,” and certainly not their social gathering; there are other occasions for that. The liturgy’s aim is our reaching out (vertically) to God in homage and supplication, and God’s (equally vertical) reaching out to us in the form of his Word and his Mysteries. In other words, worship is essentially our vertical ascent to God and the equally vertical descent of God to us; both of these actions occur in sacramental forms, that is, ontologically. (136–37)

Against the Grain of Human Nature

Right around the same time as Fr. Aidan Nichols published his important little work Looking at the Liturgy: A Critical View of Its Contemporary Form (Ignatius Press, 1996, and now out of print), in which he cites the work of religious anthropologists against the rationalist decisions made by the Consilium, Fr. Luykx was writing in his memoir something remarkably similar:

Religious anthropology…was perhaps the scholarly field most overlooked by the postconciliar liturgical renewal. Yet it is crucial. Mircea Eliade has shown in several of his books, including The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, that the Sacred is not only a basic and primary ingredient of human life; it is also the particular object and “element” of worship, as water is for fish. As Father Josef Jungmann often warned the subcommission leaders (but alas! he was unheeded), the Novus Ordo was essentially built up outside the perspective of the Sacred and its demands. Proof of this is that the two “lungs” of the Sacred —reverence and symbolism —have practically disappeared from worship. And “worship” without symbolism and reverence (holiness) is a contradiction in terms….

If our worship has been a truly sacred action and not just a civil social party, holiness will flow over into our whole lives as our outreach to God and his outreach to us. Therefore, the usual argument that “life is sacred by itself without any need for all these pietistic frills” is utterly wrong. Every honest person experiences from his daily sins that this argument is a great lie.

The same reasons apply to symbolism, the other “lung” of the Sacred, which has been discarded from the new liturgy as much as possible, under the pretext that modern man has no feeling for symbols but goes directly to the “reality.” This is another lie: look, for instance, at the logos on our modern youngsters’ T-shirts, their use of incense, their expressions of love. Symbols are finally and essentially vertical and climb up to a hidden meaning beyond their materially-graspable elements. (138)

The author then specifies examples of this desacralization and desymbolization:

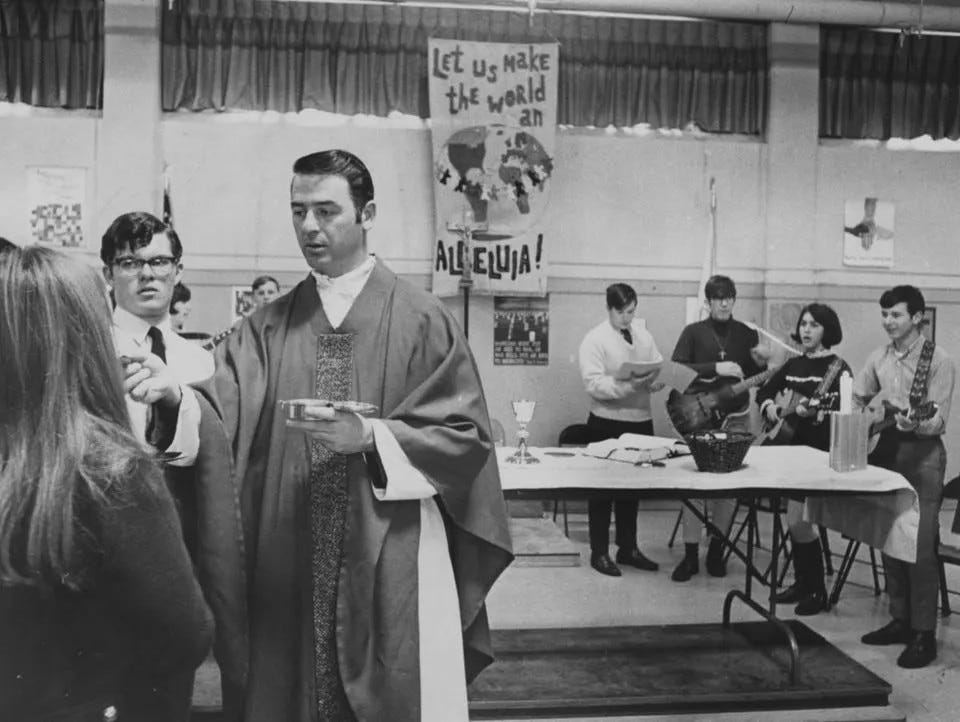

The new liturgy contains several trespasses against true anthropological laws, as follows. The dropping or abbreviating of all repetitions of ritual formulas and gestures. The repeating of ritual formulas and gestures is a basic anthropological principle in worship…. Simplified vestments. The loss of symbolism resulting from any essential simplification of vestments is to be regretted…. The destruction of sacred space. Modern liturgical dissenters categorically reject the holiness principle we discussed above in reference to church buildings and other sacred spaces. In their thinking, sacred space does not exist: it is the person who makes space holy, because (they say) the person is holy in whatever he does, unless it is manifestly sinful. Thus for dissenters there is no longer any difference between the Sacred and the profane. Yet throughout history the consecration of the church building has always been one of the major Christian rites. It is the solemn occasion in which the bishop “hands over” to God this space exclusively for his worship, just as a neophyte is handed over to God in baptism in water and the Spirit.

The failure to understand sacred space is an extension of the failure to understand the liturgy’s vertical dimension, the orientation toward God, compared to which all else is secondary. For modern liturgists a church is a horizontal gathering place of the people; hence they encourage talking before and after services in order to build up “church” by socializing, which radical horizontalism considers just as sanctifying as worship. Thus too the sanctuary is no longer preserved as a sacred space; it has even become a place for secular performances, some of them outright blasphemous….

This erroneous attitude has tragically caused some pastors to invite architects of a secular mindset to “renew” their old, wonderful churches, turning them into empty, dead shells, devoid of devotional items or statues (are the saints no longer our friends?), and putting the tabernacle somewhere in a corner. Thus they have made the church a show hall rather than a home for prayerful worship or a place to “hide away in God.” I remember Professor Émile Lousse, the famous historian of Louvain University, saying repeatedly that the main witness of a culture is its public buildings. What poor witnesses these new churches are! This heart-rending destruction has been accomplished with the money of the poor, in witness to the poverty of our spiritual culture, withered away at the hands of ministers who no longer seem to know to whom the House of God belongs. (139–40)

The poor state of liturgical music is another result of neglecting the laws of religious anthropology…. Pedestrian language is a further example of the new liturgy’s violations of anthropological principles…. Worship requires a holy language, permeated with reverence and awe of God, thus lifting up the worshipers to truly meet with God and the divine world. (140–41)

The core of this crisis consists in moving the center of being from God to man, from the vertical to the horizontal. Yet in reality the essential dimension of all liturgy is a vertical orientation toward God in praise and sacrament; therein it meets with the ontological structure of human soul and society. This orientation toward God is, anthropologically seen, the strongest and most indestructible motivation for relationships (such as love between persons); it calls for ritual to build up personality and society. (143)

The whole thrust of our post-Christian crisis, then, is the destruction of this liturgical undergirding of human life. Here is the key point: as liturgy is the first victim of the crisis, working to restore true worship must be one of the first tasks in any effort to overcome the crisis and restore true culture— and such work will produce the first benefits. If one understands this fact, he will understand the importance of my in-depth coverage of the postconciliar liturgical crisis in this book. (144)

Our author is not yet finished launching his barbed arrows!

Sacrifice and prayer — especially contemplation and mysticism — are forgotten items in the postconciliar “new church” and new world…. All this requires a true conversion. Conversion contains two movements: a turning away and a turning toward. We must turn away from all forms of self-conceit and ego-centeredness which have denatured true worship and true Holy Tradition, including seeing the Church as an institution and the liturgy as its entertainment…. We must turn toward the priority of prayer and holiness and reverence in the liturgy, in order to enter, body and soul, into the life-giving mystery that is celebrated. (144–45)

He ends the chapter with a resounding quotation from Dietrich von Hildebrand’s The Devastated Vineyard:

The new liturgy actually threatens to frustrate the confrontation with Christ, for it discourages reverence in the face of mystery, precludes awe, and all but extinguishes a sense of sacredness. What really matters, surely, is not whether the faithful feel at home at Mass, but whether they are drawn out of their ordinary lives into the world of Christ—whether their attitude is the response of ultimate reverence, whether they are imbued with the reality of Christ. (145)

Grave Consequences of Liturgical Unwisdom

In chapter 5, Luykx considers the descent from bad liturgy, to disobedience and rebellion, to apostasy and total surrender to secularity. Against the backdrop of John Paul II’s permission for altar girls, the Assisi gatherings, the Pachamama veneration, and the Abu Dhabi declaration, one can only shudder to read these words from Luykx:

Egocentric horizontalism has been perhaps the seminal principle of the postconciliar crisis. Such horizontalism has gradually sapped Christianity of its life, as a tragic revenge of Father Bugnini’s haughty rebuke of Bishop Malula. Once this man-centeredness was entrenched, it was easy to throw God out altogether. Into this vacuum moved the egalitarian relativism of strident feminism; then came pagan inculturation that adapted everything to the measure of man, not God. Finally the New Age entered, as the new religion in which man becomes his own god. (148–49)

Nor is liturgical reform unimplicated in the descent into infidelity:

Worship [is] the objective carrier and expression of the Mysteries of revelation and salvation. If worship is stripped of its symbolism and beauty, and especially of its continuity with Holy Tradition, the channels of revelation and salvation are blocked. This has often happened in the new liturgy, where the faith element is weakened or destroyed by secularism. The new liturgy is often so stripped to a skeleton that it loses not only its ritual nourishment but also its appeal to the faith of both minister and faithful. Such an impoverished liturgy perfectly fits into a secular context, but not into the continuity of Christian Tradition. (152–53)

So seriously does our author take the principle of Tradition that he argues that a newly composed anaphora is a contradiction in terms:

From the very first publication of the alternative Anaphoras (Eucharistic Prayers) after the Council, I have defended the apparently Lefebvrist thesis that no one has the right to “compose” new Anaphoras. These prayers belong to the most important patristic documents of the Early Church as testes Traditionis [witnesses of Tradition], a quality that no later author can appropriate. Adapting existing canons may be allowed, but composing new ones is not an option. (161)

More broadly:

If, at a certain moment, especially under pressure of a “paradigm shift,” an alienation intrudes into worship and especially into its sacred language, not only are worship and sacred Writ grievously jeopardized, but the creative continuity of a culture as flowing from its mysterious wellsprings of anthropology also suffers an irreparable break…. The dissenters say that modern man needs change—constant and absolute change—and that we must destroy all that represents going back, conserving, keeping tradition. They think the Fathers represent the opposite of the needs of modern man and the Church; thus they reject the Fathers and Holy Tradition as the core of all culture and hence of all inculturation. (162–63)

Betrayed by the Pope

Perhaps not too surprisingly, Luykx, at the time he composed his memoir, was an ultramontanist—someone who believed that dissent is characterized by departing from the wisdom of the pope, and that the only path to healing is strict obedience to the pope (then, John Paul II). It was relatively easy to hold this view when the pope, at least officially in writing, seemed to be stern against liturgical abuse and favorable to the recovery of reverence.

At one pitiful moment in the book, however, one sees the fragile scaffolding of ultramontanism sway dangerously in the winds:

For those opposed to the concept of altar girls, learning of Rome’s permission was a painful, heartbreaking experience. They felt betrayed by those upon whom they had depended—and whom they had supported—for many years in a bitter struggle for orthodox teaching and proper worship, in the true spirit of the Council. Crushed by Rome’s apparent failure to support their faithfulness, they could reach only one conclusion: that Rome had given in to pressure, trying to appease the unappeasable. It appeared that Rome had given permission for altar girls as a consolation prize to the very ones who had fought viciously against her regarding Pope John Paul II’s prohibition against women’s ordination.

Although many things about this situation are not clear, I am sure of one point: the official explanation for allowing altar girls—that it was merely the further application of the new Roman Code [of Canon Law]—is insufficient, not to mention offensive, to millions of faithful, loving, and obedient followers of the Church authorities. Even if this were the reason, the Church authority making such decisions is supposed to keep in mind the whole moral and psychological context of such a permission, especially in view of possibly scandalizing the faithful: for example, the context of a culture where altar girls are psychologically out of place, and the context of an age-old liturgical tradition where worshipers are accustomed to a certain visual acceptance of dramatis personae. (164–65)

The impact of the altar girls decision upon ecumenical relations with our Orthodox brethren and especially the Eastern Catholic Churches also should have been strongly considered by Rome. In all the Eastern Churches, women saints enjoy a much more significant place in liturgical and popular veneration than in the West. But it is always in reference to the Mother of God—who never played a liturgical role in the Church. Hence, the concept of “altar girls” is truly shocking to Eastern Christians.

Apart from that unsubstantiated and likely untrue claim about women saints in the East vs. in the West, I merely note that Luykx is unwilling to attribute this decision to John Paul II, though he must surely have realized it could not have happened without his approval, indulgence, or surrender.

Inculturation or Deculturation?

Coming from a man who spent decades in Africa and helped design the Zaire Use, the critique of “inculturation” as typically promoted should be taken utterly seriously:

The great message of our time is that Christ is the only solution, and hence Christianity is the only valuable counter-culture. Worship is the counter-culture’s most active element, as the main carrier, expression, and guarantee of the gospel and Holy Tradition. Consequently, the Church’s worship cannot be the experimental garden of theologians, liturgists, and misguided clergy. This is, of course, precisely the message of this whole book and, I dare claim, the very teaching of the Church and Holy Tradition.… True inculturation presupposes the presence of a valuable culture already in place, a culture in living continuity with the message that Christianity wants to convey. In the modern West such a culture no longer exists: we have a culture of death instead of a culture of life, man-centered horizontalism instead of the God-centered verticalness of prayer and the gospel, and “having” instead of “being.” (168)

The liturgical renewal after Vatican II has become like a miscarriage or stillborn baby, because of the man-centered impatience of those appointed to bring it to its rightful maturity. They believe only in the “here and now” because they believe only in themselves. They have rejected the objective norms of Holy Tradition and the creative power of the Holy Spirit in it that binds the past to the present, creates the future, and hence is the soul of true culture. (169)1

Summing up his view:

Liturgy has become a toy in the hands of these destructive movements, and the poor and lowly have become the victims of their pernicious game. As I noted above, the dissenters recognize the ultimate primacy and necessity of the liturgy; this is why they use the liturgy as their battlefield…. To force upon our poor ones a totally horizontal liturgy— in an unholy space, with tasteless music and untheological language— is to force them to live in a sterile world of lies where Holy Tradition and the Spirit of God are choked and true spiritual life cannot bloom. I am not saying that the aborted liturgical reform is part of this world of lies; it is rather its victim. Yet it belongs to the same cultural family, and its product certainly cannot be called good liturgy. (173)

Again:

Modern novelties hide the mystery by their man-centeredness and thus prevent it from giving birth to its mystical reality in the participants. The present-day false freedom of improvising the celebration is precisely the opposite of the Eastern liturgical ethos…. An Eastern priest celebrating the liturgy…appears to be totally free in his celebration, but he is guided by a thousand and one freely-accepted regulations. Hence the liturgy is not improvised by him (even though he puts himself wholly into it) but is received from Holy Tradition, his loving master that makes him truly free before the face of God, the angels, and the worshipping community. (181, 183)

The Good Old Days

At one point, Fr. Luykx’s reminiscences about his (Roman-rite) childhood in Belgium permit him to see the treasure that was present before the Council (in spite of the “incomprehensible Latin”!) and was subsequently lost by the machinations of men who talked about inculturation but destroyed real culture:

When I was a boy, my home province of Limburg, in Flemish Belgium, was still very Christian: 95 percent or more of its people were practicing Catholics. All of life in villages and cities was imbued with and regulated by religious practice. For instance, before the big feasts everyone went to confession and, on the feast itself, they went to one or often two Masses plus lengthy Vespers in the afternoon or Compline in the evening. Our huge church was packed, with standing room only.

Everything was in Latin so we did not understand the actual words, but over the whole celebration hovered a holiness, an awe stronger than words alone could convey, even for us young boys. This mystery of holiness was carried home and confirmed in friendly sharing, a good meal, and just the joy of being together.

Only later did I discover the deeper layer, the mysterious wellspring of this richness. It was the unspoken but strong awareness of belonging together as one people of believers, not only horizontally and socially, but also vertically, in the age-old tradition. We celebrated the feasts the same way our forefathers did; it was the right way and had to be preserved.

This deep awareness was especially strong on All Saints’ Day. The commemoration of the deceased began in the afternoon, with the full Office of the Dead (it was very long, but no one complained). Afterward, everyone went to the cemetery right behind the church, to flower the graves of loved ones and pray for the repose of their souls. A devout meal followed, and old memories of the family were revived. All this made a lasting impression upon us children. That was real liturgical culture! (169–70)

When Fr. Luykx comes to the question of what went wrong in the West—how was it possible to sink so low—his remarks sound more traditionalist than ever:

Unhappiness with Tradition, and rejection of it, are among the greatest troubles of the Western dissenters…. As Orthodox theologian Vladimir Lossky has said, “Tradition is the life of the Holy Spirit in the Church.”… The West, influenced by the security of having supreme authority in the Church, and bolstered by a later legalism and nominalism, has largely lost its sense of the living Tradition and even its very understanding of it. The West therefore turned more and more to law and legalism, to authority and institution… (183)

In the East—and the Council confirmed this for the whole Church—the hub of ecclesiology is the bishop, successor of the apostles. But the bishop is not an autocrat. His authority is always in reference (silent or outspoken) to his fellow bishops and to the Petrine Ministry. In the East, all bishops and even Patriarchs (the heads of the various Churches) are under, subservient to, living Holy Tradition, in the awareness that it is ultimately the Holy Spirit who governs the Church in continuity with Pentecost. The reality is that no hierarch, from a simple bishop to the pope, may invent anything. Every hierarch is a successor of the apostles, which means that he is first of all a keeper and servant of Holy Tradition— a guarantor of continuity in teaching, worship, sacraments, and prayer. (188)

Note that it is the Holy Spirit who takes over [our lives thanks to chrismation], not a Church institution or organization or authority. As important as organization and authority might be, they are only an expression of this deeper, mystical reality of the Spirit ruling the Church of Christ, and ruling every Christian from the moment of his or her confirmation. (190)

Conclusion

Although everyone will find matter for disagreement in Fr. Luykx’s theological memoir A Wider View of Vatican II, his words, quoted here at length for the reader’s illumination and edification, show him to be a man utterly committed to the good of souls and the glory of God. What a valuable witness, critic, and counselor he proves to be for a Western Church in the throes of decomposition (to use fellow liturgist Fr. Louis Bouyer’s term) — a Church that, needless to say, still possesses within herself all the resources needed to flourish anew, if only she will once again humbly embrace her own unwisely discarded tradition.

Hear us, O Lord, and have mercy!

Thank you for reading, and may God bless you.