SPECIAL: Damning Exposé of Bugnini in Prominent Liturgist’s Rediscovered Memoirs

Firsthand witness of the Consilium's betrayal of Catholic tradition

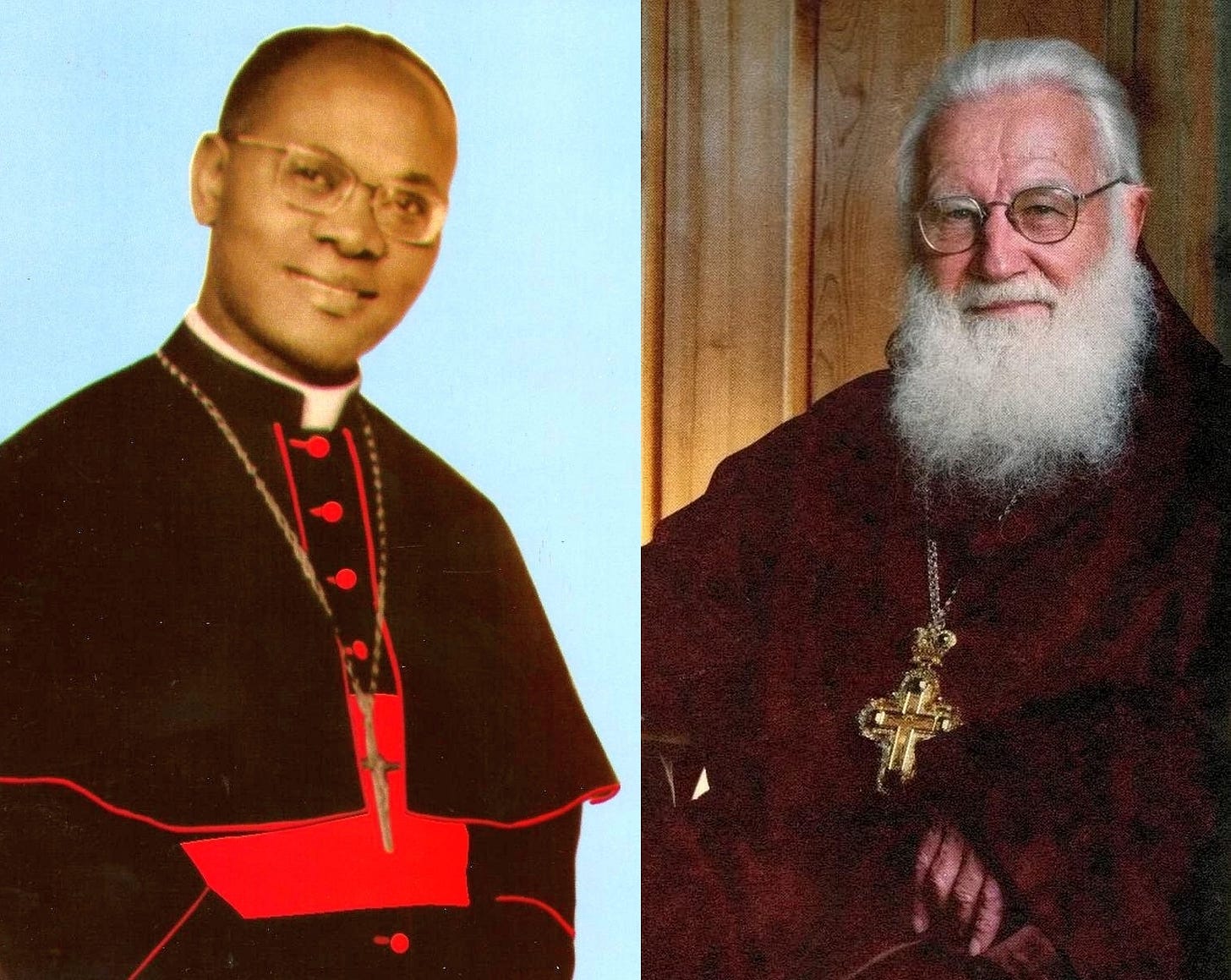

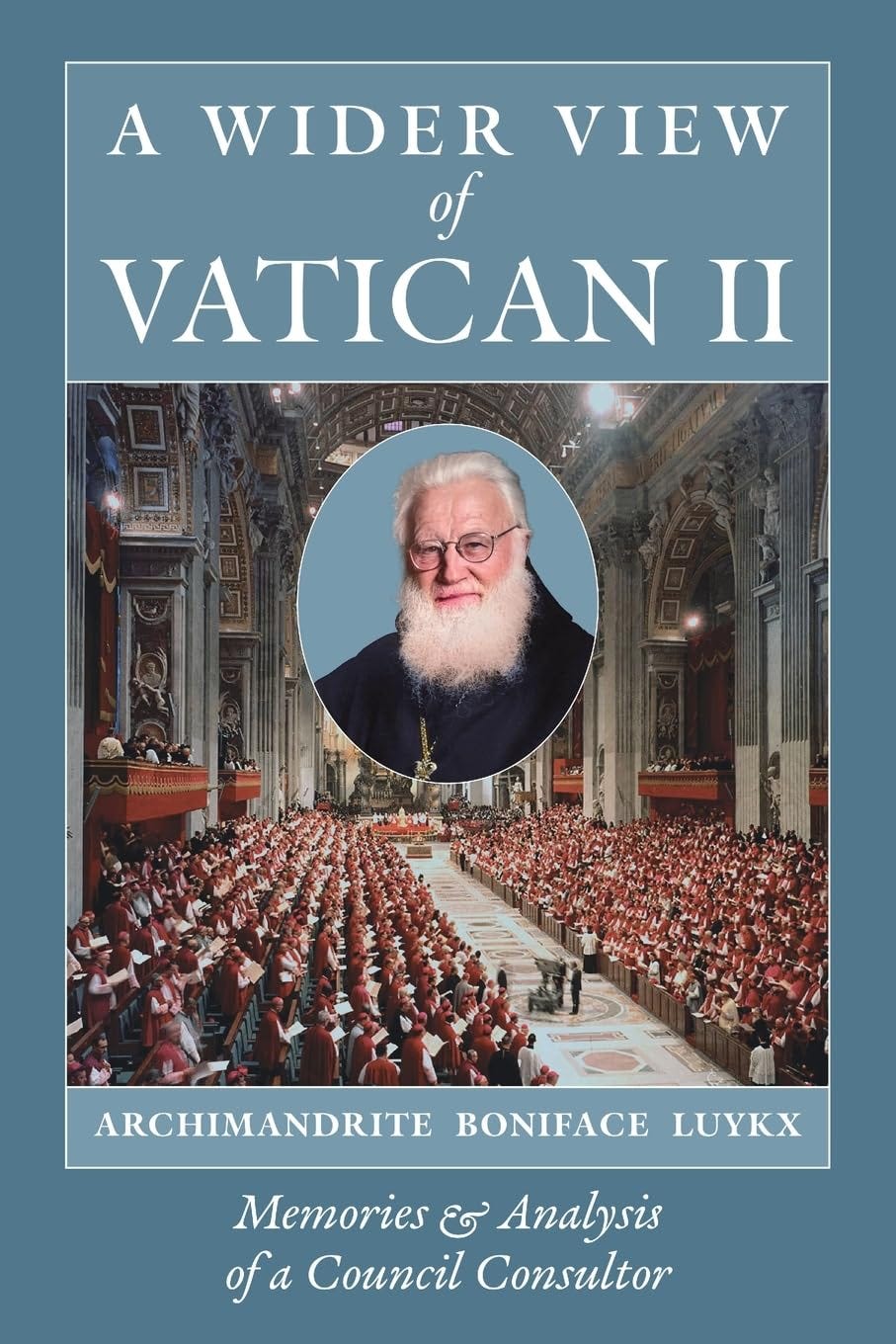

Archimandrite Boniface Luykx is not exactly a household name.

Yet he was a very important figure in his day—and his theological memoir just published by Angelico Press, A Wider View of Vatican II: Memories and Analysis of a Council Consultor, will put him back on the map.

As a priest-scholar active in the preconciliar Liturgical Movement (he was close friends, for instance, with Lambert Beauduin), as a participant in the preparatory liturgical commission for the Second Vatican Council, as an expert for an African bishop at all four sessions of the Council, and as a member of the infamous Consilium [super-committee] that produced the Novus Ordo, Archimandrite Luykx is uniquely positioned to offer an insider’s view of the good, the bad, and the ugly. This he does with zesty prose and uninhibited frankness in a remarkable personal testimony, completed in 1997 but believed lost until it was recovered in 2022.

(The “lost and found” aspect may remind you of two other important works: Louis Bouyer’s Memoirs, which were stuck in a drawer for decades until, at last, the same redoubtable Angelico Press published John Pepino’s translation in 2015, and Fr. Bryan Houghton’s hilarious and profound Unwanted Priest, which was believed lost until the manuscript was rediscovered in 2020 and then published, once again by Angelico, in 2022. Like the householder of the Gospel, Divine Providence is pulling out these eye-opening works at just the right moment, when their message will fall on receptive ears.)

Luykx’s ravishment with the preconciliar Liturgical Movement, his Byzantine-colored critique of the preconciliar Roman Rite, and his ebullient (if at times embarrassing) enthusiasm for John XXIII’s Council make his withering critique of the postconciliar reform and its anarchic reception all the more credible and powerful, for he is no grinder of axes.

Refreshingly, he is not afraid to name names; significant new information on Annibale Bugnini will be of particular interest to many readers here. This will be my focus in today’s post, where we will examine hitherto unknown—and rather unsavory—details about the inner workings of the reform, including an episode where Bugnini snubbed an African bishop, telling him that only modern Western man’s perspective counted.

I was tempted to paywall today’s post, but I really want this information to be widely disseminated, so I decided to make it free and open to the public. Nevertheless, I hope many of you will take advantage of the SPECIAL OFFER that ends TOMORROW:

Subscribe to Tradition & Sanity for 25% off:

Here are the benefits for you:

Full access to Monday’s Exclusive

Full access to all the archives, where you’ll find a lot of good stuff

Being an integral part of the greater mission of this Substack: the promotion of Catholic Tradition by a line-up of authors ready to deliver their best (we currently have seven contributing writers!)

General Impressions

Our author does not have a particularly rosy view of the situation after Vatican II:

The sacraments are being desecrated and man’s need for the holy and for reverence is being violated under the pressure of secularism, sanctioned by the dissenters’ “new liturgy.”… My own unhappy experience, during many years of work in the postconciliar subcommissions appointed to implement the Council’s documents, was that from the very beginning, some commission members in high positions never intended to abide by the scope or spirit of the Council decrees; they intended rather to promote their own ideas. Their spurious interpretation was largely foreign to the Council decrees and was rather that demanded by current fads and by liturgists and theologians of certain schools…. This awareness of the ruling, normative value of Holy Tradition wherein all the Councils’ authority is rooted has practically disappeared in the modern Western Church, under the pressure of rebellious theologians, some of whom have totally rejected Holy Tradition and are essentially in a state of heresy. (4, 5, 7)

Again:

I am convinced that the Consilium’s subcommissions misunderstood their true task and hence, wittingly or unwittingly, betrayed the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. (8)

More broadly:

We will follow the postconciliar passage from Church crisis to world crisis, from occasional disagreement to organized dissent, from differences of opinion to open rebellion, from legitimate adaptation to neo-paganism, and from God-centered verticalism to man-centered horizontalism…. I will present both theological and anthropological analyses of the postconciliar decay, showing, among other things, how the deterioration of the liturgy has led to deterioration in many aspects of life in the Western Church, and thus even in Western civilization. (9)

There was—and still is—nothing less at stake than the very survival of the Church and of Christian civilization. This threat to her survival comes not from a “spontaneous evolution” resulting from practices becoming worn out or meaningless, but rather from an organized and concerted agenda of actions that aim, by all available means, to tear down the Church and destroy Christianity. While many leaders of the Church and Christianity are sleeping, the wolves are decimating the unsuspecting flock. (11)

With laser-like precision:

The dissenters recognize the ultimate primacy and necessity of the liturgy; this is why they use the liturgy as their battlefield. (12, italics in original)

Luykx praises the German abbey of Maria Laach in the 1940s/50s, before things got out of hand:

Maria Laach Abbey…was the undisputed center of the Liturgical Movement and a center of spiritual renewal for all of Western Europe. On an average Sunday eighty busloads of spiritual seekers visited Maria Laach, magnificent in both its physical setting and its worship. The liturgy was celebrated there more beautifully than one can imagine: faultless yet naturally reverent, amidst a dignified yet sincere brotherly love. How often I heard visitors say, “This is heaven on earth; it couldn’t be more beautiful.” (26)

He summarizes the preconciliar Liturgical Movement thus:

The deep impulse of the whole renewal movement, including in America, was a striving for true piety and a return to the sources of Christianity —completely the opposite of the destructive resentment of today’s dissenters. To my great sorrow I must report that many of the renewal movement’s leaders in both the United States and Europe, some of whom were my dear friends, gradually lost the movement’s original vision and no longer promote its goals. Mais où sont les neiges d’antan. How have the old dreams vanished. (30–31)

The true nature of liturgy has been perverted, resulting in social, man-centered, desacralized “services” in which awe and reverence for God’s holiness have all but disappeared…. In the heart of the Church today there exists a decay precisely the opposite of the goals of both the Council and the preconciliar renewal movement. Why was it that Christians in the decades before the Council thronged to the European abbeys that were hearts of the renewal? Was it to be entertained by popular novelties or have their ears tickled by new teachings? No; they came to share in true worship, enlivened by a solid hunger and respect for the holy, for reverence, and for objective authenticity. By participating in reverent worship and embracing objective truth, the people were freed from their unredeemed subjectivism and the often-prosaic banality of daily life. (34)

Enter the Vincentian Secretary

The first substantive mention of A.B. comes on page 45:

Father Annibale Bugnini, editor of the journal Ephemerides Liturgicae and professor at several Roman institutes, was our Secretary [for the Preparatory Commission for Liturgy prior to Vatican II]. He was a very capable man and an adroit politician with a special charism for bringing people together and bridging oppositions. As we will see in the pages to come, he exerted a strong (and often problematic) influence in the liturgical developments during and after the Council. (45–46)

With gentlemanly discretion, Luykx states:

In between sessions of the Preparatory Commissions, while most of us were working on our assigned tasks in our home countries, certain men in Rome were also busy, but in a less honest way. Some of them, thinking they had the field free for their obscure operations, went so far as to change the conclusions reached by the Members at previous sessions. In our Preparatory Commission for Liturgy, we strongly suspected a certain monsignor of doctoring texts that the Commission had approved but were not to his liking. In the aftermath, some have seen this underhanded activity as part of a general plot, but it has not been proven. (52)

When Luykx arrives at Paul VI’s creation of the Consilium, he turns up the heat:

Between the preconciliar and postconciliar times, then, something changed drastically—including in the Council’s commissions entrusted with its work. After the Council they became more and more infected by a new high-handed spirit whereby some commission members put themselves and their opinions above the Council documents on which they were supposed to work in the very spirit of the Council Fathers. Worship became the primary victim of their high-handedness, but this man-centered viewpoint also deeply affected the problem of religious liberty and the Church in the world. It was essentially a switch from the objective, vertical ascent toward God to the subjective, horizontal gravitation in man. (81)

The members of Pope Paul VI’s Consilium and its subcommissions (including myself) began their work of interpreting CSL [this abbreviation refers to the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy] in January 1964. Thus began the first phase, a time of creative work of fellows: study, meetings, and discussions within the subcommissions. This work was initially good, but it soon became infected by erroneous attitudes. (82)

Now we get into the heart of the matter:

In the beginning of our postconciliar work, the spirit of excitement and brotherhood was strong and generated good results, as long as the experts stuck to the text and spirit of CSL. I would like to remember the experts primarily as scholars who wanted to serve the Church.

But after working with them for some time, I came to see how their personal differences began to dominate: their belonging to this particular school or order or country, their view on the importance or unimportance of history and Church Tradition, their past scholarly work, their personal likings. Many of these men were in-depth research scholars, lopsided toward their own field of study. Secretary Bugnini, who was rather a horizontal “overview scholar,” often gently overcame these experts’ tyrannical misgrowth and brought them to agreement beyond their specialty. But personal differences quickly came to claim the status of absolute values which the more aggressive experts imposed upon others.

So gradually a rift grew among the experts. Two factors were involved. First, the ambitions, characters, and idiosyncrasies of both persons and groups became more and more blatant and difficult to handle; the situation was especially difficult between some Germans and French. Second, some experts broke more and more away from fidelity to CSL, valuing their own opinions above the Church and the Holy Spirit. These men became highly aggressive and often prevailed in the final decision-making process, as we will see. Some of my most painful memories of this period are of certain experts’ reckless tyranny, which had harmful consequences for the whole Western Church. (85)

Interestingly, contrary to the normal traditionalist narrative (which I personally share, but I want to give every historial source a fair hearing), Fr. Luykx believes that Bugnini was sound and sincere before the Council but that something “snapped” afterwards. Here are his own words, as he shares a very revealing episode:

The trend away from adherence to CSL spread to the top, to Secretary Annibale Bugnini. Throughout the Liturgical Movement, the Preparatory Commission for Liturgy, and Pope John’s Consilium [here he’s referring to an earlier body, in 1962-63], Father Bugnini had been faithful to Tradition and the Magisterium. But after the Council he changed. Based on my personal friendship with him, I believe that this change arose not from purposeful malice, but rather from weakness. He seemed to me very impressionable: if someone pushed him one way, he went that way; if someone pushed him the other way, he went there instead.

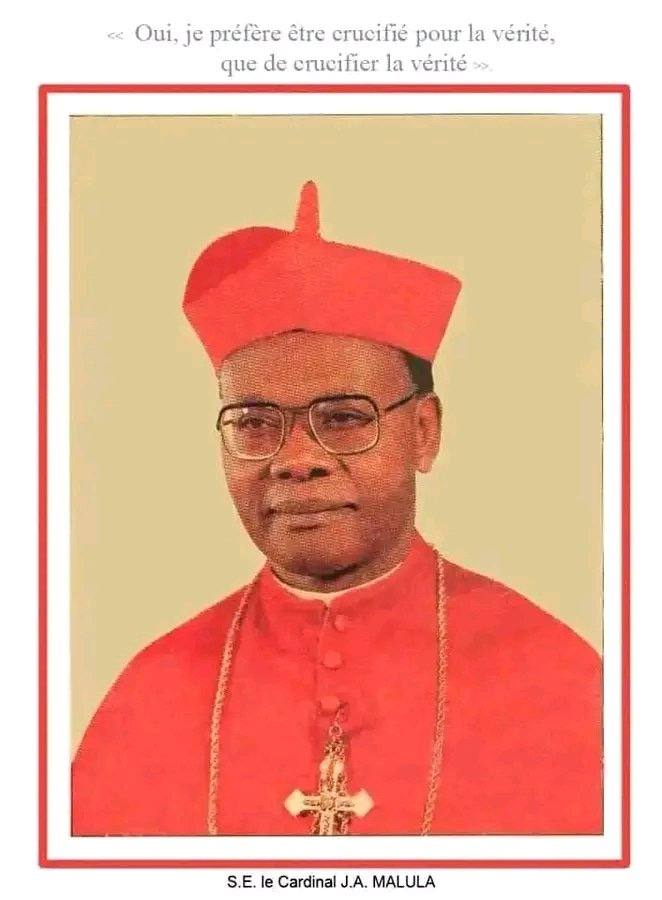

But Father Bugnini was also a politician, and one who wanted power. In order to gain power he had to appear successful, so he went along with those who were the most vocal and apparently powerful. He was heavily influenced by the modernists who broke from fidelity to CSL, the most outspoken of whom was Johannes Wagner from the Trier Institut in Germany. Before long, Bugnini stopped inviting to the meetings those “reactionary” members who dared to adhere to the text of CSL or to sound principles of religious anthropology. I know this as fact, because Bishop Malula and I were among those who fell out of his favor.

What role did Bishop Malula and I play in the midst of this growing tension and polarization? After a short time, Bishop Malula lost all desire to participate in the subcommissions. The revolutionary boutique of scholars made him feel useless; they treated him as an ignoramus and even insulted him. In addition, the subcommissions’ entire work was going counter to CSL and was useless for the mission countries, especially those of Africa. Bishop Malula stated this fact more than once to Secretary Bugnini. On such occasions Bugnini answered the good bishop with remarks so atrocious they are forever etched in my memory:

“Bugnini: If you cannot agree, set up your own commission in Africa.

“Malula: Where will our Church, poor as a beggar, get the funds to do such a thing, while you here avail yourselves of the money of the whole rich West?

“Bugnini: N’importe [it doesn’t matter]. We here work from the assumption that the modern Western man is the man tout court, the model of all true humanity, for all countries and cultures, and for all ages to come.”

That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Furious over such an arrogant and absurd insult, Bishop Malula vowed never to return. He authorized me to replace him and instructed me accordingly. I suppose Father Bugnini and his people were happy to be rid of an “enemy,” according to the emerging policy of excluding those who were faithful to CSL.

We will return later to Father Bugnini’s revealing response to Bishop Malula, for it became apparent that his opinion about the supremacy and normative value of modern Western man was part of his agenda—and consequently part of the agenda of the Consilium’s subcommissions he oversaw.

At this point, one might ask the obvious and serious question: from whence does one man, or group, get the right to impose his way of praying or celebrating upon the whole Western Church? This question goes to the heart of the dubious validity, or at least the liceity, of much of the work of the Consilium’s subcommissions, for they often worked in defiance of CSL, the only authoritative norm given by the Council. (86–87)

One of the last general meetings of the Consilium was dedicated to liturgical language. I was to give a paper on how the new Christian cultures (such as Africa’s) saw this problem. Bishop Malula and I spent several hours in deliberation and study to bring together all our experience, for the profit of the Church. The bishop, a highly-cultured man and outstanding linguist, had worked his entire adult life on building up a Christian language, in the vernacular, fitting for Holy Scripture and worship in Africa. His strong conclusion was this: worship requires a holy language, permeated with reverence and awe of God and thus lifting up the worshipers to truly meet with God and the divine world.

So I gave my talk, opening with a description of Bishop Malula’s experience and continuing with my own anthropological research. But my presentation was generally rejected. The experts had already made up their minds: they had no intention of learning from these half-wild Africans! They had already decided that the new liturgy was meant for the poorly-educated, secularized, modern Western man (the model of future culture, as Father Bugnini had said). They reasoned therefore that its language should be on this same under-civilized level —not street language per se, but close to it—so there would be no break between the liturgical services and man’s usual language outside of them. I strongly protested. In revenge, they decided not to mention my talk in the index of the proceedings. (88)

Later in the book, Luykx returns to the startling interview and comments on its significance:

Father Bugnini’s statement, made twice in my presence, is important for two reasons. First is the persons involved. Bugnini was Secretary of the Consilium and thus had enormous influence over the subcommissions’ operation and results. Bishop Malula was the only representative of the African continent, and he henceforth boycotted the meetings in protest. Second is that Bugnini’s arrogant statement in fact rendered well the policy of the Consilium. Thus we see that the subjective, not the objective, theological standpoint of the Consilium’s Secretary (and its members) was a strong factor in decisions regarding the postconciliar liturgical documents. (132)

Father Bugnini and the proponents of change believed that the first and real foundation of “good worship” was its horizontal (i.e., man-oriented) dimension, and that its vertical (God-oriented) dimension was secondary, following from the other…. This is perhaps the primary cause of the demolition of the postconciliar Roman liturgy. The primacy of the horizontal is the basic principle of the agenda of the second postconciliar phase. In this principle, liturgy’s first dimension is horizontal, as a social action of the people to create a down-to-earth sharing among the participants. The result of horizontalizing worship is the almost totally socialized and man-centered dimension of the liturgy now found in most parishes. But this destroys the most basic meaning of all worship. It is a tragic desacralization of Christian worship, where man, not God, is central, and the liturgy becomes a fireside affair, a civil performance intended to make everyone feel happy, as in some Protestant groups. (135)

This horizontal image of man embraces the attitude that the model for man is the science-man that Father Bugnini had in mind: the human being who stands totally free from all depth-dimension, all religion, history, and tradition, and is rather geared totally toward the present reality. (150)

Quite astonishingly, Luykx views Josef Jungmann as a conservative ally in the struggle against the ideologues!

Some spiritual giants like Father Josef Jungmann exercised a soothing influence, although he was firmly opposed to some iconoclastic novelties being proposed, including the altar facing the people, an issue we will discuss later. I shared the disappointment of Father Jungmann and many other dear friends in the Consilium at the iconoclasm of our rebellious colleagues. (77)

As Father Josef Jungmann often warned the subcommission leaders (but alas! he was unheeded), the Novus Ordo was essentially built up outside the perspective of the Sacred and its demands. Proof of this is that the two “lungs” of the Sacred—reverence and symbolism—have practically disappeared from worship. And “worship” without symbolism and reverence (holiness) is a contradiction in terms. (138)

Luykx also relates how the bishops, when attending certain wrap-up meetings in order to vote as the ones with hierarchical authority, felt as if they were cornered by the experts and pushed in a certain direction:

At most of these sessions, I felt I was assisting at a joke, for the bishops were often manifestly manipulated by the relators —some of whom dared even to silence the bishops for their “incompetence”!

In the aftermath, some bishops told me they felt obliged to approve “the wonderful work of these all-competent experts.” Indeed, more than once in subcommission meetings I had heard bishops say, “You experts are appointed by the Church to work all these things out; the Church trusts you because you are experts. It makes no sense that we, who are not specialists, would presume to correct your work, on which you have labored so long and assiduously.” Other bishops later expressed privately to me how much they regretted the course those events took, knowing it was because they themselves “let things go,” feeling unable to change them in the face of the impenetrable wall of the experts’ perceived competence. The experts’ aggression and the bishops’ lack of real intervention explain the tenor of the documents and why many are so lacking in the pastoral dimension.

I have been a professor of theology and liturgy at several colleges and universities for almost fifty years. During that time I have gathered broad experience of the tragic inbreeding and incompetence of many who are called “experts” and “scholars.” Sadly, many of them, especially the most aggressive ones, do not deserve the confidence placed in them. (91–92)

The archimandrite expresses displeasure with many particular results of the Consilium. Thus, he speaks of “the mongrelized combination that has become the Western Rite of Confirmation” (76), and notes that “the suppression of the subdiaconate was inconsistent with a return to the ancient sources as intended by the Council Fathers” (94); as for the rite of the consecration of churches, “the dropping of some valuable Carolingian elements deprived the rite of symbolism that had given it the mystery-filled dramatics so beloved by the faithful —and which had been an element of ecumenical rapprochement with the East” (ibid.).

Strikingly, he identifies the Novus Ordo Missae as “certainly…a new liturgy” (which he thinks was never called for). Indeed, his account of why Paul VI accepted it is rather disillusioning:

One of Pope Paul’s queries of these Protestants [who had been invited as consultants to the Consilium] had been whether or not the planned Mass rite, the Novus Ordo, would bring the Catholic Church closer to her Protestant brethren. It is asserted that the Protestants’ unanimous “yes” tipped the scale toward its final introduction. I personally asked Father Louis Bouyer, who was close to Paul VI, what influenced the pope to choose the Novus Ordo. He said in essence that the pope was instructed and convinced by the subcommissions’ rebels that the Church, and the Protestants, wanted this Mass. So the pope said, in essence, if that is so, I give in. The Novus Ordo was indeed favorable toward ecumenical efforts with Protestants—but it gravely hurt those efforts with the Eastern Churches, contrary to the Council’s intent. (99)

His sobering words on the reception of the Novus Ordo are worth underlining:

Loyal and orthodox liturgists were perhaps the most disappointed by the new Missal. They knew that perfection and unanimity are impossible, but they also knew there is quite a distance between a particular option and a mediocre result which comes from constantly compromising on essentials. They immediately recognized that the Novus Ordo exceeded all measure of compromise. Moreover, they were critically aware of this fact: the Novus Ordo is not faithful to CSL but goes substantially beyond the parameters which CSL set for the reform of the Mass rite. (98, emphasis in original)

The wry remark on the vernacular hits the nail on the head:

For many people, the vernacular was the great “savior” that overshadowed and justified all the other changes; unfortunately, however, it became a sort of narcotic that dispensed them from further critical thinking. (100)

I should also mention in passing Luykx’s complaint that the new liturgical calendar “looks much like an abstract exercise,” in which “the element of popular devotion was systematically removed, in disregard of its role as one of the basic ingredients of a living liturgy. For instance, the authors adopted mostly recent saints and dropped many earlier ones who still enjoyed popular veneration” (95).

His appraisal of the Liturgy of the Hours is particularly noteworthy:

The postconciliar writers essentially created a new Office, contrary to the instruction of CSL 23…. The flaws in this new Office are many; here I will emphasize just one. If the Divine Office is to be truly the “prayer of the Church,” it must be provided a dual structure and ethos—one for private prayer and one for recitation or singing in common. Some patterns for ease of singing, such as the Gregorian or Byzantine systems of eight tones, should have been built in. But the president of this subcommission refused to allow a dual structure, and the Office was treated as a text to be merely read or silently meditated upon, not celebrated…. This subcommission’s experts took as their paradigm “praying a private text” instead of “celebrating a liturgy of prayer”; hence they failed to provide actions or rubrics or gestures (except eventually incense at the Magnificat in Vespers), which would have been of great benefit.

This situation urges us to again ask the question: Who in the Church has the right to impose his way of praying upon the whole Church? And who has the right to interrupt the centuries-old organic flow of prayer tradition in the Western Church and also to ignore the ancient tradition of her sister Churches in the East? (95–96)

I will postpone to a future post Fr. Luykx’s detailed critique of the inadequacy of the Novus Ordo as religious ritual (but if you happen to pick up the book before I get around to that post, you’ll find the relevant material on pages 104 to 120).

Some caveats on the book

The editor of A Wider View of Vatican II, Julie Rogers, who knew Archmandrite Luykx well and served for a time as his secretary, comments that Abbot Boniface

shared with me, in deep sorrow, that some of [his Liturgical Movement friends] (including a few mentioned in this book) became part of the postconciliar “rebellion.” He said that men such as these, to varying degrees, gradually abandoned their foundation of deep prayer, spiritual discipline, and humble devotion to the Mother of God. As a spirit of pride took hold, they started considering action more important than prayer —and valuing their own opinions over Holy Tradition and the Council’s primary documents they were tasked with implementing. (xxii)

Now, it is true that many writers (including myself) view Sacrosanctum Concilium as by no means innocent of blame, but here is not the place to go into that question (those who are interested will find a detailed treatment in the opening chapter of my book Close the Workshop, and in Christopher Ferrara’s classic article “Sacrosanctum Concilium: A Lawyer Examines the Loopholes”). But the larger point made by Luykx and echoed by Rogers deserves emphasis: the liturgical crisis has spiritual roots; the new rite reflects and transmits the indiscipline, arrogance, secularity, and activism of the men who designed it. This is one reason among many why its use is spiritually dangerous: from a bad tree cannot come good fruits.

Oddly enough, Abbot Boniface still thinks the reform can be reformed—a view only a few of the most ostrich-like human beings still hold at present. We’ve had Ratzinger for pope, Ranjith, Cañizares, and Sarah as liturgy czars, Burke as head of the Signatura, Müller in the CDF, and so forth, and the needle hasn’t even crawled a millimeter towards any of the goals of the ROTR.

No, it’s dead in the water, and that’s because the formative and normative principles of the Novus Ordo stand in conflict with the elements of tradition people wish to bring back. If you want them back, you need to bring back the liturgical rite in which they find their natural and necessary home. Period. It’s a package deal, you take it all or you leave it all. It’s precisely the “pick and choose” mentality that has dissolved ritual coherence like sulphuric acid.

In the interests of transparency, I will state that Luykx is what one might call “an equal-opportunity offender”: there is something in this book to set off just about anyone in the liturgical debates. If you love the Latin Mass, Luykx will tell you why it’s hopelessly in need of reform, and why no one before the Council ever really participated, since they understood nothing and had no proper role, etc.—all the old chestnuts about what’s wrong with the Tridentine rite. At the same time, if you love the Novus Ordo, he will tell you why it’s a betrayal and a failure, a pathetic substitute for tradition. I am not really surprised that this liturgist who began in a Western religious community ended in an Eastern one: he was critical of nearly everything Western! You will never find a more colossally Byzantophilic author than he.

Luykx, in short, is a curious mythical creature, half-progressive and half-traditional, an antiquarianist and a believer in building better liturgy by committee (just so long as it’s not the committee that actually did it). My quotations above represent Luykx at his most “traditionalist” in tone. But if you read the book, you will find passages reminiscent of Mary Healy that may induce pain. He paints a rose-colored picture of the preconciliar liturgists, holds Jungmann’s corruption theory, and seems more than a little naïve about nouvelle théologie and ressourcement. Luykx is no friend of the classical Roman Rite; he considers Latin an impenetrable obstacle to participation, he favors married priests, the permanent diaconate, concelebration, communion under both kinds, the charismatic movement, and African adaptations; indeed, he was a co-author of the “Zaire Use.”

All that being said, both conservatives and traditionalists will be able to rally around characteristic statements such as these:

“The atmosphere of the celebration of the liturgy must be holy, clothed in awe and reverence, as befits the redeeming Presence of God’s Majesty and our answer to this Presence” (67);

“the authority of, and real recourse to, Holy Tradition take precedence over all other considerations, including adaptation” (73);

“a break with true Tradition is always a disaster for the piety of the faithful and often for the liturgy itself. Hence there is no provision for creating a new Mass, a new liturgical year, a new Divine Office, et cetera” (76).

In any case, to read theological memoirs of a priest, monk, and liturgist who helped write Sacrosanctum Concilium and worked alongside Bugnini is a rare privilege. You might say this book is a comprehensive commentary on one of the most poignant things Joseph Ratzinger ever said:

Anyone like myself, who was moved by this perception [of the liturgy as a living network of tradition] in the time of the Liturgical Movement on the eve of the Second Vatican Council, can only stand, deeply sorrowing, before the ruins of the very things they were concerned for.

A Wider View of Vatican II: Memories and Analysis of a Council Consultor by Archimandrite Boniface Luykx. Edited by Julie Rogers. 258 pp. Paperback $19.95; hardcover $32. Also available at Amazon.

Thank you for reading, and may God bless you!

Again and again Arch. Luykx's observations reminded me of problems in other sectors of society, indicating that the diabolic assault is across the culture, not just against the Church: The condescension towards Africans by erstwhile progressives remains true today, as in a similar way does the hypocritical rewriting of black-white relations in the US, wherein one political party rails against the legacy of slavery while it was (and arguably is) responsible for perpetuating race hatred now and segregation for over a century in the past; also, the exalting and giving free rein to "experts," has its counterpart in the running amok of the medical-scientific community which was only fully-revealed during and after the manufactured COVID "crisis." (Analogous to the need to fix the imaginary liturgical crisis.)

The great abbot was in fact a Norbertine during the time of the council, and was always one officially. He gave the juniors of our abbey a retreat when I was young, always wearing our habit, and I drove him around before and after. He was altogether engaging and did not have the frequently encountered snottiness of many of those who go over to the Byzantine rite. He was too learned for that ! Thanks for this! We’ll get a copy! Fr Hugh Barbour, O. Praem.