His Heart in Hiding: The Priesthood of Gerard Manley Hopkins, SJ

A life short in years but rich in suffering, offered in union with the Host

In late September 1877, in a quiet corner of Wales, Gerard Manley Hopkins, newly ordained to the priesthood, ascended the altar for the first time. The Jesuit chroniclers did not record the day of his first Mass.1 Of all that is known of his life, this intimate detail remains appropriately hidden. The moment must have been unspeakably precious for him after a painful conversion and nine long years of preparation. With the fragrance of chrism lingering on his hands, he took up the paten, and prayed the Offertory in a low voice:

Suscipe, sancte Pater, Omnipotens aetérne Deus, hanc immaculátam hóstiam, quam ego indígnus fámulus tuus óffero tibi Deo meo vivo et vero, pro innumerabílibus peccátis, et offensiónibus, et neglegéntiis meis, et pro ómnibus circumstántibus, sed et pro ómnibus fidélibus christiánis vivis atque defúnctis: ut mihi, et illis profíciat ad salútem in vitam aetérnam. Amen.

Accept, O holy Father, almighty and eternal God, this unspotted host, which I, Thy unworthy servant, offer unto Thee, my living and true God, for my innumerable sins, offenses, and negligences, and for all here present: as also for all faithful Christians, both living and dead, that it may avail both me and them for salvation unto life everlasting. Amen.

The words, with their lovely poetic excess and ineffable sacredness, with their doctrinal clarity and spiritual power, rang through Hopkins’ priestly heart in union with Christ’s offering to the Father,2 and in perfect harmony with the cherished prayer of Saint Ignatius of Loyola:

Súscipe, Dómine, univérsam meam libertátem. Accipe memóriam, intellectum atque voluntátem omnem. Quidquid hábeo vel possídeo mihi largítus es; id tibi totum restítuo, ac tuae prorsus voluntáti trado gubernándum. Amórem tui solum cum grátia tua mihi dones, et dives sum satis, nec áliud quidquam ultra posco. Amen.

Take, Lord, and receive all my liberty, my memory, my understanding, and my entire will, all that I have and possess. Thou hast given all to me. To Thee, O Lord, I return it. All is Thine, dispose of it wholly according to Thy will. Give me Thy love and Thy grace, for this is sufficient for me.3

How blessed is the priest whom God in His infinite mercy allows to make the Church’s Suscipe his very life! Lex orandi, lex credendi, lex vivendi.

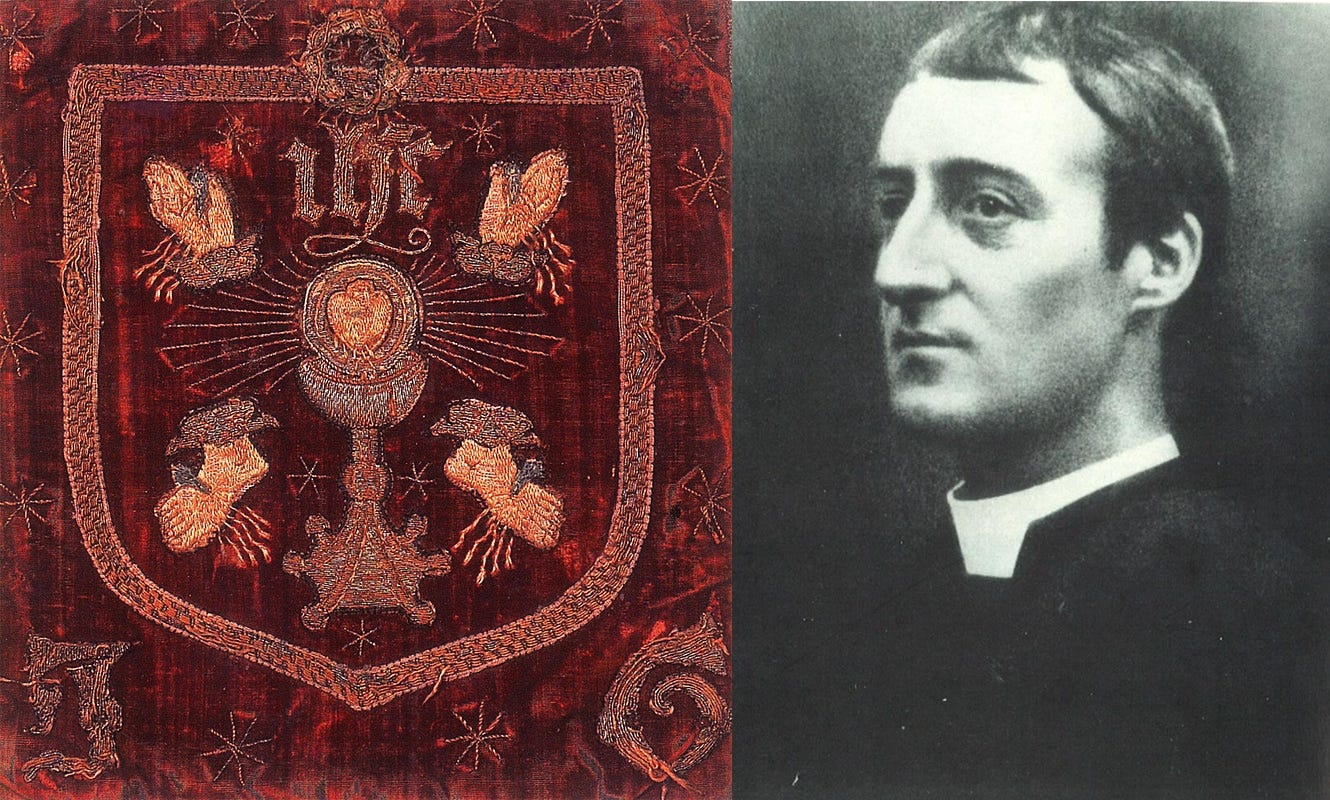

As in the words of the Offertory, Hopkins’ soul was also to be subsumed into the prayer of Consecration. He was now, and forever more, an alter Christus, at one with the Host, his spirit taken up and consumed with the ceaseless offering of the Divine Victim, symbolized by the Heart pierced and burning in the Breast of God as on the ancient altar of Sacrifice.

The Heart of the Host

The Heart of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament was ever the center of Hopkins’ priesthood, in a life short in years but rich in suffering. This Heart was his heroic ideal, the mainstay of his interior life and his labors among the poor, his literary inspiration, and the source of his perseverance in his religious vocation. In life and in death, Hopkins’ profound interior desire to gather his life into a complete self-offering has been one of the most challenging aspects of his psychology for both critics and admirers to understand. This ideal, his Suscipe, impelled him to burn his juvenile poetry and to begin a religious vocation with the Jesuits. It is likewise this sensitivity for Christ’s own self-offering that caused the first-year novice to weep uncontrollably as the pre-sanctified Host was carried to the sacristy on the evening of Maundy Thursday.4

From the beginning and above all, it was a love of the Blessed Sacrament that drew him to the Catholic faith. As an undergraduate at Oxford in 1864, long before he entered the Catholic Church, or had even spoken to a Catholic priest, he counseled his friend E. H. Coleridge:

The great aid to belief and object of belief is the doctrine of the Real Presence in the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar. Religion without that is sombre, dangerous, illogical, with that it is—not to speak of its grand consistency and certainty—loveable. Hold that and you will gain all Catholic truth.5

Two years later, the young Hopkins had reached an impasse regarding his belief in the Real Presence. He could no longer in conscience delay his conversion from Anglicanism to Catholicism. On October 16, 1866, Hopkins wrote his father, Manley:

But you do not understand what is involved in asking me to delay and how little good you wd get from it. I shall hold as a Catholic what I have long held as an Anglican, that literal truth of our Lord’s words by which I learn that the least fragment of the consecrated elements in the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar is the whole Body of Christ born of the Blessed Virgin, before which the whole host of saints and angels as it lies on the altar trembles with adoration. This belief once got is the life of the soul and when I doubted it I shd become an atheist the next day… What end then can be served by a delay in which I shd go on believing this doctrine as long as I believed in God and shd be by the fact of my belief drawn by a lasting strain towards the Catholic Church?6

He concluded his letter with a youthful, even stern appeal to his father, whom he dearly loved:

At least for once—if you like, only once—approach Christ in a new way in which you will at all events feel that you are exactly in unison with me, that is, not vaguely, but casting yourselves into His sacred broken Heart and His five adorable Wounds. Those who do not pray to Him in His Passion pray to God but scarcely to Christ.7

The Heart alight was the choicest of the five Wounds—these being the signal banner under which Englishmen had fought and died at the time of the Reformation. What was it that the Catholics had fought and died for, on the Northern wastes and on Tyburn Tree? For the Catholic Faith; for the Mass. The Faith, the Mass, the Wounds, the Heart could only ever be one for an English Catholic, and so they were for Hopkins.

The Faith was salvation, which could not be found in Anglicanism. Hopkins feared that an accident might take his life, and he would lose his soul by his hesitation. Furthermore, he refused to forego sacramental grace.

And so, he went resolutely to Rome and Holy Mother Church by way of Birmingham. He was received by St. John Henry Newman into the Roman Catholic Church on October 21, 1866. By converting, Hopkins was alienating himself from his family, forsaking a hopeful future, and setting himself forever outside of the privileged society in which he had spent his entire life. But there was always a heroic strain in Hopkins, a passionate desire to follow his ideal, and his ideal was Christ himself—Christ the Victim, Christ the Altar, Christ the Eternal High Priest.

After his conversion, he returned to Oxford to finish his education; then for a short period he served as a teacher in Newman’s Oratory school. During that time, he devoted himself to discovering his vocation. Hopkins’ discernment of religious life remains shrouded in mystery. His choice seemed to lie between the Benedictines and the Jesuits. Once again, Newman made his paternal influence felt, and affirmed Hopkins’ desire to join the sons of St. Ignatius. “I think it is the very thing for you,” the kindly Oratorian wrote. “Don’t call the Jesuit discipline hard, it will bring you to heaven.”8

Hopkins entered the Jesuit novitiate at Roehampton on September 7, 1868, the eve of Our Lady’s birthday. The subsequent years, though by no means easy for him, were rich in intellectual growth and creativity. He studied philosophy, discovered the work of John Duns Scotus, and immersed himself in moral theology. After an ascetic period of seven years in which he wrote little or no verse, he took up his pen again. The natural beauty of Wales inspired some of his best poems, for he met Christ His Lord everywhere—in the falcon’s flight, in starlight, in the faces of men. Above all, Hopkins found Him in the heart of the Host, though it was a Heart, like his own, often in hiding.

Consider Hopkins’ description of his own conversion in stanza 3 of The Wreck of the Deutschland:

I whirled out wings that spell And fled with a fling of the heart to the heart of the Host. My heart, but you were dovewinged, I can tell, Carrier-witted, I am bold to boast, To flash from the flame to the flame then, tower from the grace to the grace.

The Times Are Nightfall

After his ordination, things changed rapidly. Hopkins, thrust into the thick of school and parish life, was continually moved around by his superiors wherever a spare preacher or substitute priest was needed.

Consumed with his labors, he had little time and no repose of spirit to pursue his literary art to his or anyone else’s satisfaction. Hopkins’ friends and family, like many contemporary literary critics, believed his life and poetic talent had been tragically wasted. The Jesuit publications of the time consistently refused to publish the poems he did produce, while on the other hand, his friends viewed his priesthood as an unfortunate accident inhibiting his true artistic vocation.

But Hopkins himself had taken the measure of the sacrifice he was making. A little over four years after his ordination, he would write his friend Canon Richard Watson Dixon9:

My vocation puts before me a standard so high that a higher can be found nowhere else. The question then for me is not whether I am willing (if I may guess what is in your mind) to make a sacrifice of hopes of fame (let us suppose), but whether I am not to undergo a severe judgment from God for the lothness I have shewn in making it, for the reserves I may have in my heart made, for the backward glances I have given with my hand upon the plough, for the waste of time the very compositions you admire may have caused and their preoccupation of the mind which belonged to more sacred or more binding duties, for the disquiet and the thoughts of vainglory they have given rise to. A purpose may look smooth and perfect from without but be frayed and faltering from within. I have never wavered in my vocation, but I have not lived up to it.10

Campion, Xavier, Rodriguez. These men were his spiritual fathers in the Society of Jesus. What had Hopkins to show for four years of his priesthood? “I have not lived up to it.” He had been moved six times, never abiding more than a few months in one place. His superiors struggled to find a fitting role for him; in spite of, and perhaps because of his literary genius, he was not an effective preacher for the common folk. His health, chronic depression, and personal eccentricities seemed always to keep him from living the heroic sanctity he so deeply desired.

This cultured Oxford man, one of the greatest poets of the English language, this spiritual son of St. John Henry Newman, breathed no rarified air. His priestly work took him deep into the slums of industrial Liverpool and Glasgow. Poverty, drunkenness, horrific vice: day after day for almost two years, he traversed the unwholesome, dark streets ministering to his lost sheep, those poor Irish Catholics who had come to England seeking work in the hellish factories and shipyards. He saw youth broken and innocence corrupted. He breathed the filthy, sulphurous air and worked himself into terrible sickness in the suffocating summer heat. He said Mass and he sang Mass, anointed the dying, and tended to the destitute poor through his work with the St. Vincent de Paul Society. Brutality and disease were the daily portion of his poor afflicted heart. He sat for uncounted hours in the confessional, listening to the endless tales of human woe and misery brought forth by his hapless penitents. Overwork nearly killed him.

He wrote to Canon Dixon:

My Liverpool and Glasgow experience laid upon my mind a conviction, a truly crushing conviction, of the misery of town life to the poor and more than to the poor, of the misery of the poor in general, of the degradation even of our race, of the hollowness of this century’s civilisation: it made even life a burden to me to have daily thrust upon me the things I saw.11

Harder Hope and Dearer Love

His interior struggles brought him even lower. Hopkins’ was a sensitive soul, finely attuned to physical beauty in nature and in the human person; at the same time, he was wracked by scruples, fearing the temptations that his sensuality posed to his chastity. He likewise strove to detach himself from his natural ambition and the desire for both temporal and spiritual success, knowing that his poetry would distract him from his priestly ministry ad majorem Dei gloriam.

Hopkins wrote to his friend Robert Bridges12 in 1879:

I cannot in conscience spend time on poetry, neither have I the inducements and inspirations that make others compose. Feeling, love in particular, is the great moving power and spring of verse and the only person that I am in love with seldom, especially now, stirs my heart sensibly and when he does I cannot always ‘make capital’ of it, it would be a sacrilege to do so.13

Christ, who had drawn him into the Church, into the Jesuit order, and into the depths of depraved industrial society, had fallen silent. Yet, though experiencing extreme desolation, crippled with illness, and crushed under the weight of disappointment, Hopkins was a priest sure of his vocation, drawn irresistibly to the sacrifice of the Altar. At the Heart of it all was the Incarnation of Christ, continued in the Mass. “Make [Christ] your hero now,” he preached at Bedford Leigh:

Take some time to think of him; praise him in your hearts. You can over your work or on your road praise him, saying over and over again / Glory be to Christ’s body; Glory to the body of the Word made flesh; Glory to the body suckled at the Blessed Virgin’s breasts; Glory to Christ’s body in its beauty; Glory to Christ’s body in its weariness; Glory to Christ’s body in its Passion, death and burial; Glory to Christ’s body risen; Glory to Christ’s body in the Blessed Sacrament; Glory to Christ’s soul; Glory to his genius and wisdom; Glory to his unsearchable thoughts; Glory to his saving words; Glory to his sacred heart; Glory to its courage and manliness; Glory to its meekness and mercy; Glory to its every heartbeat, to its joys and sorrows, wishes, fears; Glory in all things to Jesus Christ God and man. If you try this when you can you will find your heart kindle and while you praise him he will praise you.14

Here was more than simple enthusiasm, more than a fleeting pious feeling. Hopkins would pay his vows to the Lord, for the ancient Mass was his very life. In the midst of great interior suffering as he ministered in Glasgow, he wrote to Canon Dixon that he could not visit him because “if I were at Hayton I could not say mass, and hitherto since I have been ordained I have never missed doing so except when I could not help it.”15

For Hopkins, Christ was indeed silent—as silent as the Host on the paten. Had he not made the words of St. Thomas his own?16

Godhead, I adore thee fast in hiding; thou God in these bare shapes, poor shadows, darkling now: See, Lord, at thy service low lies here a heart Lost, all lost in wonder at the God thou art.

After his death, one of his Jesuit contemporaries wrote:

I think the characteristics in him that most struck and edified all of us who knew him were, first, what I should call his priestly spirit; this showed itself not only in the reverential way he performed his sacred duties, and spoke on sacred subjects, but his whole conduct and conversation; and secondly, his devotion and loyalty to the Society of Jesus.17

Triumph and Immortal Years

Suscipe—how high the cost! Gerard Manley Hopkins longed to show forth the greatness that the Reconquest of England demanded. He came of age in the shadow of magnanimous men—Newman, Faber, and Manning, among others.18 His confreres in the priesthood, many of them converts like himself, seemed to go from strength to strength. The rapid growth of the Catholic Church in England was matched by a high numbers of vocations19 and the foundation of many religious orders. The Jesuits were on the forefront of all this revival, their ranks full of men renowned for their talent and sanctity. Among such extraordinary priests, Hopkins fell quietly into the background, left to do what ordinary work lay within his fluctuating ability.

As an artist, he remained unknown and misunderstood, his poetry written in snatches and spare moments throughout the years. In the twelve years from his ordination to his death, he wrote some forty-two complete poems, not counting several fragments. He was well aware of their experimental nature, though this did not prevent him from being disappointed at every rejection. Despite the reservations of his friends, he himself had Ignatian clarity as to the place of the poems in his own life. He wrote in his spiritual notebook in 1883:

Also in some med[itation] today I earnestly asked our Lord to watch over my compositions, not to preserve them from being lost or coming to nothing, for that I am very willing they should be, but they might not do me harm through the enmity or imprudence of any man or my own; that he should have them as his own and employ or not employ them as he should see fit. And this I believe is heard.20

Throughout the years, Hopkins’ life in religion maintained an essential pattern: he was moved by his superiors from teaching post to teaching post, never abiding long in one place, never able to maintain his health and peace of mind. Hopkins was keenly aware of his stubborn humanity; he would often act and speak impulsively, a distressing trait in one who had been attracted to the Jesuit order because of its discipline and who had taken the Spiritual Exercises as the foundation of his interior life. He retained his quirks, his penchant for complex theological speculation, and his chronic depression. He struggled with his deep, even passionate need for male friendship. He failed at nearly every teaching position he was given. He endured unspeakable heartbreak as one after another of his close friends who had, along with him, converted to Catholicism apostatized.21

Hopkins suffered, but he stayed—doggedly loyal to his vocation, to the Jesuits, and to Christ his Hero, though he followed Him in footsteps of blood, and not of glory.

Finally, Hopkins was sent to Dublin to be a professor of Greek at University College. There, he labored for over five years as a teacher and an examiner. Homesick for England, his isolation and sadness reached a pitch. In January 1889, he wrote in his spiritual journal,

What is my wretched life? Five wasted years almost have passed in Ireland. I am ashamed of the little I have done, of my waste of time, although my helplessness and weakness is such that I could scarcely do otherwise.22

Yet, every sacrifice has a consummation. His own came quickly, in June of that year. After Easter, Hopkins fell ill with what he believed to be a slight fever. He wrote letters assuring his friends and family of his convalescence, but no sooner were they sent, then he fell into a critical decline, the victim of dreaded typhoid fever, endemic to Dublin at that time. His parents, initially so resistant to his conversion, rushed across the sea to accompany their beloved son in the days and hours of his final agony.

As he drew near his end, he was heard to say three times, “I am so happy, I am so happy, I am so happy.” Gerard Manley Hopkins, priest of the Society of Jesus, by the grace of God having persevered to the end, died with the last rites on June 8, 1889. It was the Vigil of Pentecost, with all its mystical signification. He had made of his life an offering in union with the host, and it had been accepted in tongues of fire:

Suscipe, sancte Pater, Omnipotens aetérne Deus, hanc immaculátam hóstiam, quam ego indígnus fámulus tuus óffero tibi Deo meo vivo et vero, pro innumerabílibus peccátis, et offensiónibus, et neglegéntiis meis, et pro ómnibus circumstántibus, sed et pro ómnibus fidélibus christiánis vivis atque defúnctis: ut mihi, et illis profíciat ad salútem in vitam aetérnam.

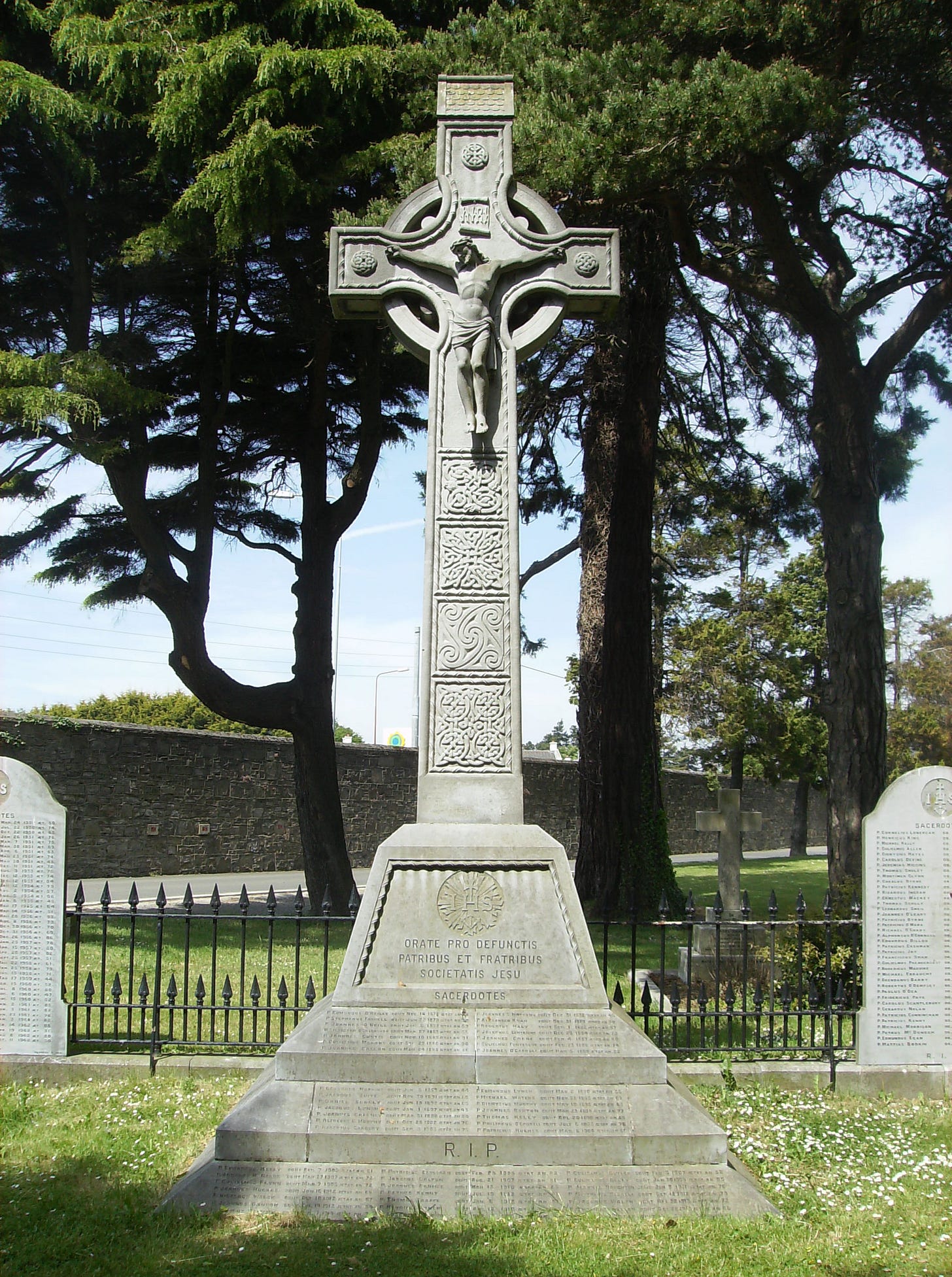

In a corner of Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, Ireland, stands a granite crucifix that towers over the little grassy hills and headstones below. Over the sleeping dead, our crucified Lord reigns from a Celtic cross, traced with endless, swirling knots. On the face of the monument, below the Crucifix, is etched a sunburst radiating the Holy Name, and below that in plain script: Orate pro defunctis Patribus et Fratribus Societas Jesu.

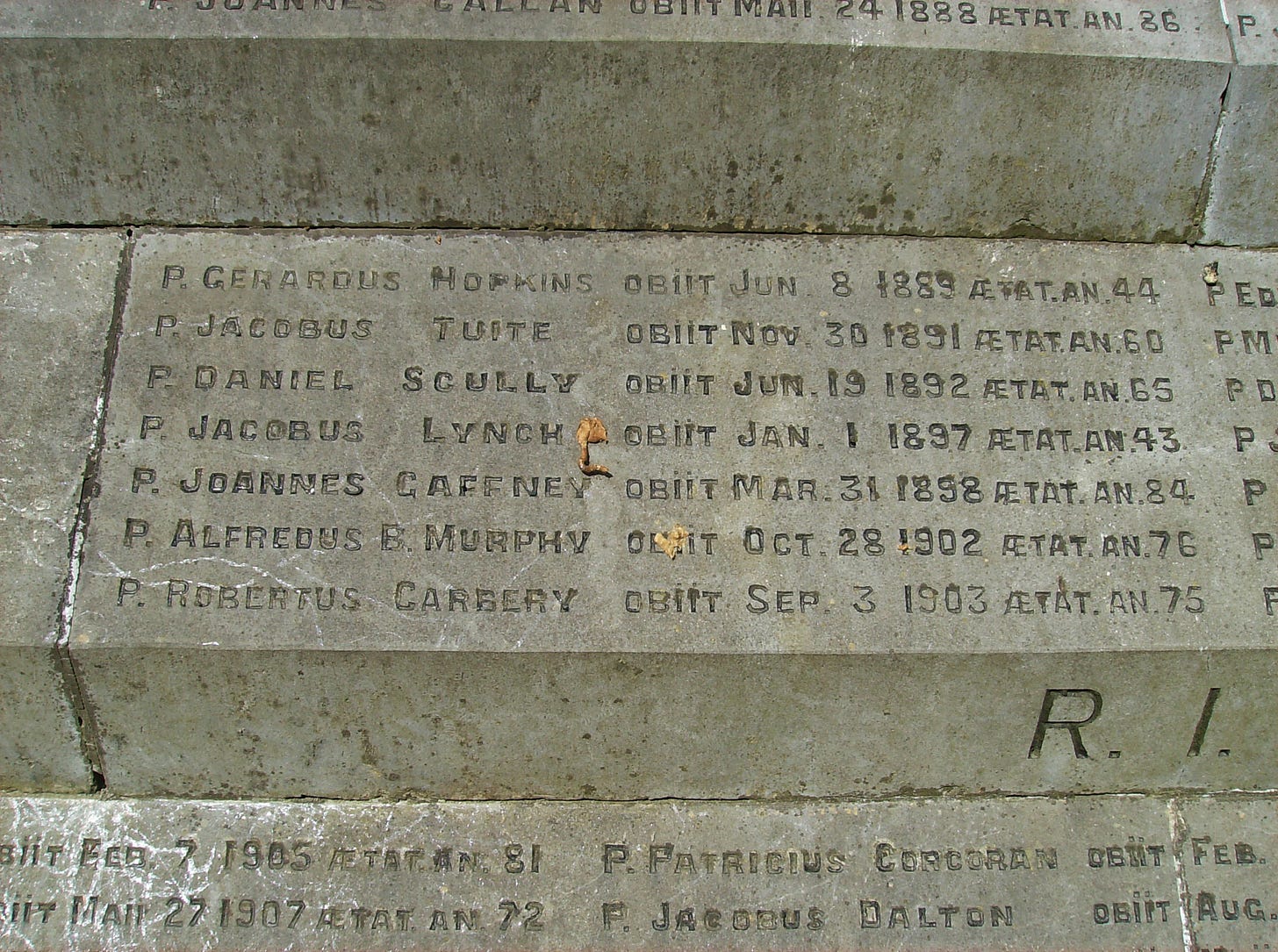

In contrast to the prominence of the Crucifix, the countless names of the priests and brothers lining the three tiers of the base of the monument, and even the remaining three sides of its upper face, fall into a blessed anonymity, like disciplined soldiers in ranks. These souls would be happy to have it so, recalling the words of the Gospel: Illum oportet crescere, me autem minui, “He must increase, I must decrease.” Hidden among the names of the Jesuits, on the front face of the second tier, is minutely carved, in Latin: P. Gerardus Hopkins, obiit Jun. 8, 1889, aetat. an. 44 [Father Gerard Hopkins, died June 8, 1889, 44 years of age].

The name in granite is a small echo of the luminous tale of Divine Grace written in the Book of Life. We should take seriously the mandate carved in stone, Orate, as Hopkins did throughout his priesthood; we should offer, in union with the priest, the precious Suscipe for the relief of his soul and all the holy souls in Purgatory, for the conversion of England, for the restoration of the Church on earth, and for the sanctification of the Jesuit order, so sadly fallen.

The secret hidden beneath the quiet sward is one with the secret whispered over the altar in 1877: the eternal Offertory first comes forth not from the mouth of the priest, but from the very Heart of Christ our King. May the blessed Suscipe, spoken on the lips of countless traditional priests for so many centuries, bring in the reign of Christ’s Heart over ours, as Hopkins himself once prayed:23

Let him easter in us, be a dayspring to the dimness of us, be a crimson-cresseted east, More brightening her, rare-dear Britain, as his reign rolls, Pride, rose, prince, hero of us, high-priest, Our héarts’ charity’s héarth’s fíre, our thóughts’ chivalry’s thróng’s Lórd.

He was ordained on September 23, 1877, at St. Beuno’s in Wales. Presumably, his first Mass also was said at St. Beuno’s.

The removal of the Offertory and its replacement by a Jewish table blessing was among the most grievous theological innovations of Annibale Bugnini and the Consilium. Since the Offertory prayer clearly defines the sacrificial nature of the Mass and the role of the priest in offering that sacrifice, one may wonder how much its abolition has contributed to the confusion of identity and collapse of spirituality in the priesthood. See Peter Kwasniewski, The Once and Future Roman Rite, particularly pages 46-47. (The bibliographyfor all sources cited in these notes may be found here.)

Translation by Louis J. Puhl, SJ.

Hopkins, Journals and Papers, 195.

Hopkins, Further Letters, 17.

Hopkins, Further Letters, 92.

Hopkins, Further Letters, 95.

Quoted in Thomas, Hopkins the Jesuit, 21.

Richard Watson Dixon (1833-1900) was an Anglican cleric and poet. He was assistant master at Highgate School at the time Gerard Manley Hopkins attended. Hopkins initiated their mature friendship in 1878 via letter. Their correspondence, mainly concerning poetry, reveals a warm mutual respect and admiration for one another.

Hopkins, Letters to Dixon, 88.

Hopkins, Letters to Dixon, 97.

Robert Bridges (1844-1930), a doctor by training, was Hopkins’ closest friend from their time at Oxford until Hopkins’ death in 1889. Their friendship was mainly carried out in letters, as Hopkins was rarely able to leave his assignments. Bridges and Hopkins frequently exchanged poems and literary criticism with each other. Eventually becoming Poet Laureate in 1913, a position he maintained until his own death in 1930, Bridges is responsible for the publication of Hopkins’ poetry in 1918.

Hopkins, Letters to Bridges, 66.

Hopkins, Sermons and Devotional Writings, 38.

Hopkins, Letters to Dixon, 58.

The following stanza is taken from Hopkins’ translation of the Adoro Te Devote.

Quoted in Pick, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Priest and Poet, 87.

The incredible achievements of the first Bishop of Shrewsbury, the Right Reverend James Brown, who ordained Hopkins, are indicative of the explosive growth of the Church in England during this time.

In the seventy or so years from the beginning of the Tractarian movement to the beginning of the 20th century, 448 English converts to Catholicism became priests (the number includes both regular and secular clergy). See Thomas, Hopkins the Jesuit, note 1 on p. 17.

Hopkins, Sermons and Devotional Writings, 252-53.

His dear friend from Oxford, William Addis, abandoned not only the priesthood, but the faith itself.

Hopkins, Sermons and Devotional Writings, 262

The Wreck of the Deutschland, final stanza.

Thank you for this. I have only ever (first as an English major, then much later as a Catholic) read about Hopkins as a poet, not as priest. I'm also currently reading Malachi Martin's book on the Jesuits and it is good to be reminded of how solid the Jesuits were for so long.

Beautiful and heartbreaking 💔