Should a Christian Be a “Restorationist”?

Is the tendency to think of the past as superior to the present and hence as offering a model for the future a legitimate or healthy attitude?

Today we are pleased to welcome the inaugural article by our new contributor Fr. Thomas Crean, OP. Fr. Thomas has been a Dominican friar of the English Province since 1995, and lives at St Dominic’s Priory in London. He has written widely on theological questions — for example, Letters From That City: A Guide to Holy Scripture for Students of Theology; Vindicating the Filioque: The Church Fathers at the Council of Florence; and commentaries on St. Mark’s and St. Luke’s Gospels. He currently teaches online for Holy Apostles College and Seminary in Connecticut.

Christianity and Restoration

Should a Christian be a “restorationist”? Naturally, it depends on what one means. Let us define restorationism as the tendency to think of the past as superior to the present and hence as offering a model for the future. Is this a legitimate or healthy attitude for a Christian to exhibit?

In good scholastic fashion, we can start with some contrary arguments.

Objection 1. Ecclesiastes seems to reject this position. Say not: What thinkest thou is the cause that former times were better than they are now? For this manner of question is foolish (Eccl. 7:11).

Objection 2. St Augustine writes: “Each stage of life, in each individual man, from infancy to old age has its own beauty. Therefore, just as it would be absurd to desire youthfulness in a man far on in years, since it would be to disprize the other beauties that come in their proper time to the other periods of life, so he would be absurd who should desire only one period for the whole human race” (Eighty-Three Diverse Questions, no. 44).

Objection 3. All periods of history are marked by original sin, and men are not more subject to original sin now than they were in the past; so, there is no reason to prefer one period over another.

Objection 4. To postulate some iron law of decline in the human race would be to contradict human freedom. Chesterton, in The Everlasting Man, has this bracing passage: “One of the ablest agnostics of the age once asked me whether I thought mankind grew better or grew worse or remained the same. He was confident that the alternative covered all possibilities…. I asked him whether he thought that Mr. Smith of Golder's Green got better or worse or remained exactly the same between the age of thirty and forty. It then seemed to dawn on him that it would rather depend on Mr. Smith; and how he chose to go on. It had never occurred to him that it might depend on how mankind chose to go on; and that its course was not a straight line or an upward or downward curve, but a track like that of a man across a valley, going where he liked and stopping where he chose, going into a church or falling down in a ditch.”

Sed contra: the Messiah is presented by the prophets as a restorer: The places that have been desolate for ages shall be built in thee: thou shalt raise up the foundations of generation and generation: and thou shalt be called the repairer of the fences, turning the paths into rest (Is. 58:12). So, it seems that, at least in religious matters, restorationism is a healthy attitude.

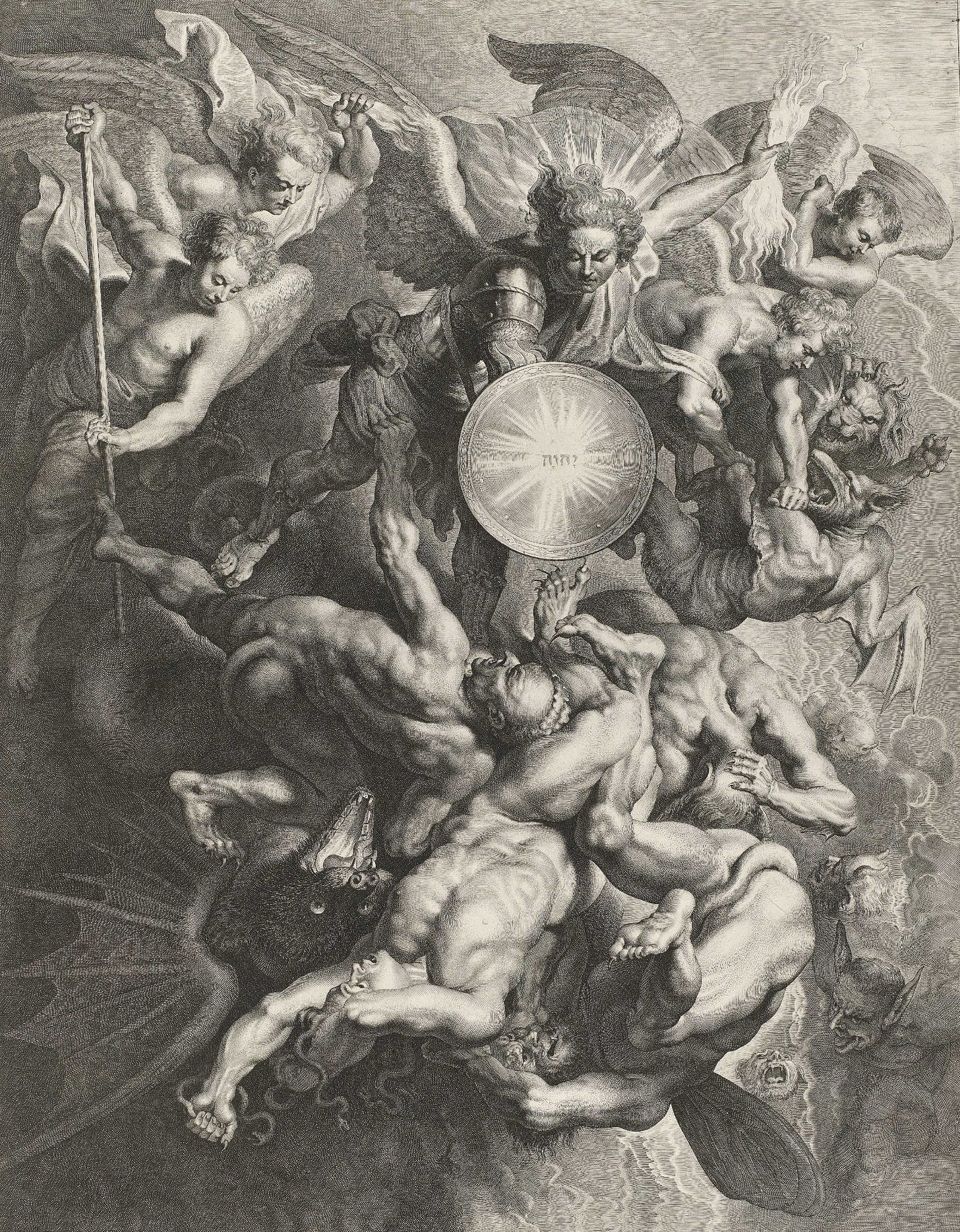

I reply: The need for religious restoration is of old date. It began long before the liturgical upheavals of the 1960s, or the replacement of Christendom by secular regimes around the time of the French Revolution, or the passing away of mediaeval scholasticism. If we follow the judgement of St Thomas Aquinas, it began at the second instant of creation. For it was then, he explains, that having been established at the first instant of their fashioning in a state of grace, a vast number of angelic spirits turned from God toward themselves and so were changed from light into darkness. The heavenly city was thus almost from the beginning deprived of a good number of its proper inhabitants.

In the opinion of St Augustine, one of the purposes of the incarnation was to restore the ruins of that city by causing human beings to occupy places left vacant by the fallen angels. As he explains in his Enchiridion on Faith, Hope, and Charity: “Jerusalem which is above, which is the mother of us all, the city of God, shall not be spoiled of any of the number of her citizens, shall perhaps reign over an even more abundant population.” St Thomas Aquinas, commenting on the words of St Paul in the letter to the Ephesians, he hath purposed to re-establish all things in Christ, [things] that are in heaven and on earth, notes: “The things that are in heaven are the angels; not that Christ died for angels, but that by redeeming man, he restores their ruin.”

As the word “redeeming” implies, man himself is to be restored. In the 2nd century, St Melito, bishop of Sardis, wrote: “Man by touching the tree broke the command and disobeyed God, and so he was cast out into this world as into a debtors’ prison.” Just as in the parable of the Good Samaritan, fallen man is both stripped and wounded. Stripped of the garment of grace, and wounded even in his natural powers, he yearns, at least in his better moments, to be restored to that original condition when, in the words of Hugh of St Victor, he did not have to seek after God as for one who was absent.

At least in a cosmic sense, then, a Christian must be a restorationist. But what about life within this fallen world? Can we expect that there will be some recurring need for religious restoration? Surely we can, and first of all on a priori grounds. Saving truth, by which we learn what to believe about God and how to worship Him, is not a product of human industry. It must come down to us from above, as St James insists.

Whilst therefore we may expect that within a given people, technological skill or the natural sciences will progress from one generation to the next, at least in the absence of war or some other disaster, we can feel no such confidence about that people’s fidelity to divine revelation. Rather, we may expect that a “law of entropy” will operate in the spiritual as in the material realm. After all, what St John Henry Newman called “those giants, the passion and the pride of man” are constantly labouring, and they will naturally tend to dismantle religion.

This explains why already in the Old Testament, an annual restoration was prescribed for the Israelites. On the day of Atonement, the high priest was to expiate the sanctuary from the uncleanness of the children of Israel, restoring the tabernacle to its pristine state of ritual purity, so that sacrifice might be offered there for another year (Lev. 16).

Human nature has not changed since then. We can expect that with the passage of time, divine worship will become tarnished by irreverence and formalism, while the moral life of Christians will grow more slack, worldly and compromised, and their acceptance of divine truth more lukewarm, partial, hesitant, and confused. To quote Newman again:

Nature tends to irreligion and vice, and in matter of fact that tendency is developed and fulfilled in any multitude of men, according to the saying of the old Greek, that “the many are bad,” or according to the Scripture testimony, that the world is at enmity with its Creator. The state of the case is not altered, when a nation has been baptized; still, in matter of fact, nature gets the better of grace, and the population falls into a state of guilt and disadvantage, in one point of view worse than that from which it has been rescued. This is the matter of fact, as Scripture prophesied it should be: “Many are called, few are chosen;” “the kingdom of heaven is like unto a net gathering together of every kind” (Difficulties of Anglicans, Lecture 9)

Of course, this is only one side of the truth. I am not denying that God raises up new saints and teachers in every age, suited to that age. As Newman puts it, having described the state of the many: “The Church at the same time is ever labouring with all her might to bring them back again to their Maker; and in fact is ever bringing back vast multitudes one by one, though one by one they are ever relapsing from her.”

Still less am I denying the great change wrought within human history by the incarnation, whereby the old law gave way to the new and eternal covenant. Nor even am I denying the possibility of some new effusion of grace upon the Church, such as many people have hoped for in connexion with a mass conversion of the Jewish people.

But although this law of spiritual entropy that I am proposing is not the only law at work in the spiritual realm, it is permanently at work—and therefore “restorationism” is warranted as a component of the permanent attitude of Christians.

That was an a priori argument, based on the downward tendency of human nature. But we can also make an argument from history, and first of all from the inspired history of the chosen people. As Joseph Shaw has noted, the Old Testament repeatedly presents to us the ideal of restoration after a period of decline or disaster, and specifically that of liturgical restoration.1

Josias, the last king of Judah to reign in peace before the coming of the Babylonians, did not only restore the temple worship to its proper purity and celebrate the first Passover since the days of the Exodus that followed all the prescribed ritual. He also rediscovered the book of Deuteronomy after it had been lost in the temple and forgotten, and put all its statutes into practice.

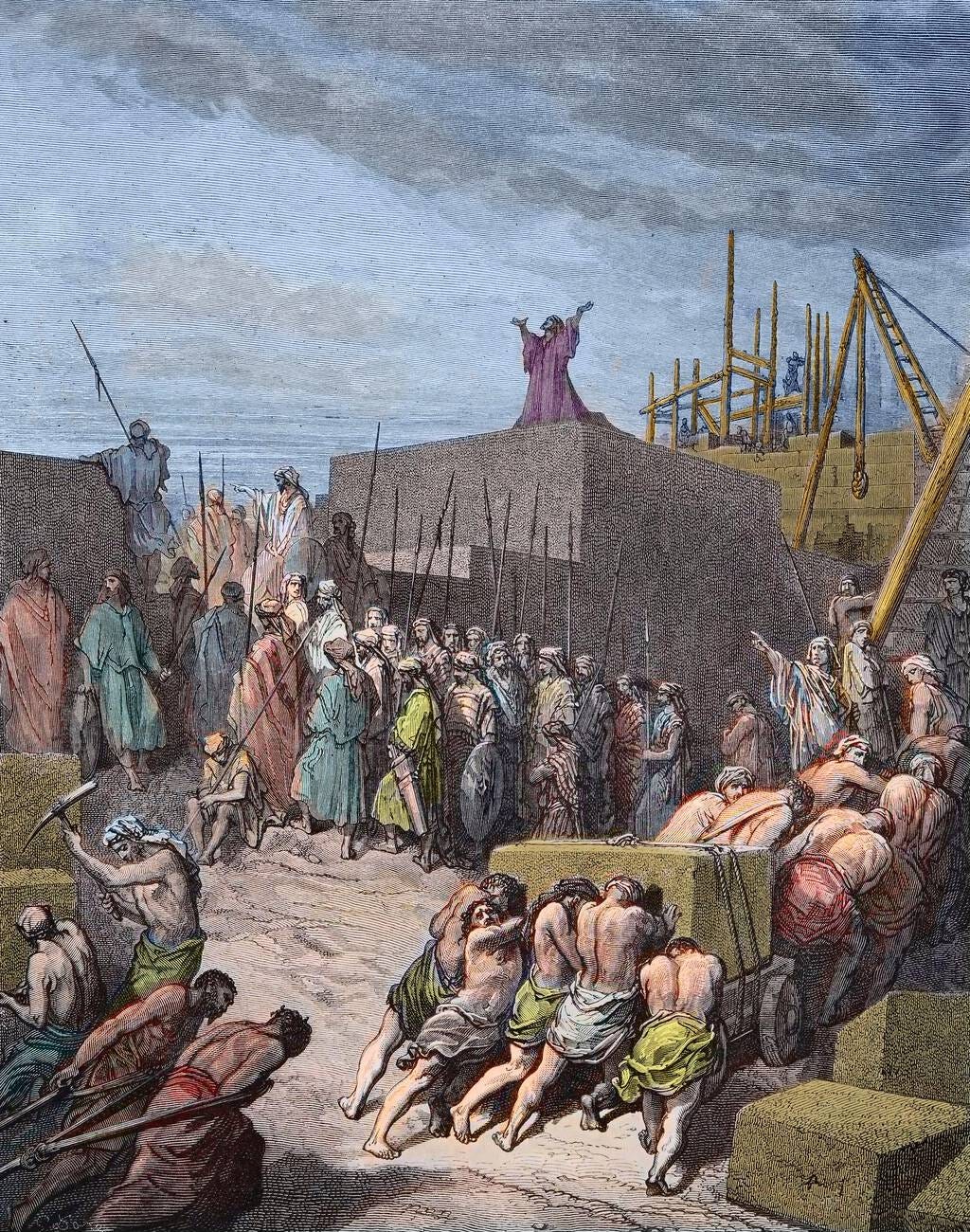

After their return from exile in Babylon, when the people in their discouragement hesitate to rebuild the ruined temple, God raises up the prophet Haggai to tell them to do just that. This people saith: The time is not yet come for building the house of the Lord. And the word of the Lord came by the hand of Aggeus the prophet, saying: is it time for you to dwell in panelled houses, and this house lie desolate?

When, after the temple is rebuilt, the old men weep as they compare its humble appearance with the splendour that they still remember from seventy years before, God sends the prophet Zechariah to comfort them with the mysterious words: Despise not the day of small things.

Another three hundred and fifty years pass. Again the sacrifices in the temple are interrupted, this time by the armies of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, and by the setting up of an idol upon the altar of God. Many of the most influential Jews judge that the time for keeping the law of Moses, inherited from a more barbarous age, is now past, and that the arc of history is bending ineluctably toward Hellenism. But once again, the will of God is for restoration.

When Judas Maccabeus and his brothers manage to recapture the temple mount, we read: They saw the sanctuary desolate, and the altar profaned, and the gates burnt, and shrubs growing up in the courts as in a forest, or on the mountains, and the chambers joining to the temple thrown down. How do they respond? First, as is natural, they lament, tearing their garments and putting ashes on their head. But then they set to work, cleansing the holy place, choosing twelve new stones to build a new altar according to the same pattern as the old one, making new holy vessels, and offering sacrifice once more according to the law.

That is why, when our Lord was born, another two long life-times later, He could be fittingly presented in the temple, in fulfilment of the prophecy of Haggai to the reluctant builders of his day: Great shall be the glory of this last house, more than of the first.

Since the sacred history within the New Testament is so much shorter than that of the Old, it has much less occasion to set before us examples of restoration. All the same, we find allusions to the tendency of human nature to fall away from spiritual excellence, and thus to a present or future need to restore what has been lost. I have somewhat against thee, says Jesus to the angel, presumably the bishop, of the church of Ephesus, because thou hast left thy first charity. Be mindful therefore from whence thou art fallen, and do penance, and do the first works.

Speaking to the clergy of the same Ephesian church, St Paul says: I know that after my departure, ravening wolves will enter in among you, not sparing the flock, and of your own selves shall arise men speaking perverse things, to draw away disciples after them. What is to be the defence against these future heresiarchs? It will be to look backwards, to the apostles. Remember your prelates, he tells the Hebrews, who have spoken the word of God to you: whose faith follow, considering the end of their conversation. Likewise, his remedy for the liturgical disorders in Corinth is to call the Corinthians back to the liturgical tradition that they have received from him, and through him, from Christ Himself.

If we turn from the pages of the New Testament to the later life of the Church, we constantly find the ideal of restoration in the lives of the saints and great churchmen. St Augustine, at the start of his rule for religious, invokes the example of the church of Jerusalem as described in the Acts of the Apostles, where all the faithful were of one heart and one mind, and held all things in common. That arrangement had long passed away, but St Augustine, in common with other religious founders, wished to recreate it in his own day and for his own community.

The liturgy of the Church likewise praises St Dominic as a restorer: in the proper preface of his feast, the priest says to God: “Thou didst will to renew the apostolic form of living through the blessed patriarch Dominic.” St Francis, also, is praised by the Church in the feast of his stigmatisation for rekindling love—the Church’s first love, you might say—when the world was growing cold.

Underlying this praise of restoration, I would suggest, is a deep sense of what I have called the law of spiritual entropy, of the inevitability of decline, but of a decline that can be to some extent resisted and mitigated by human efforts under grace. It is an attitude that is perhaps inspired by the question of our Lord to the disciples: When the Son of man comes, will he find faith on earth?, as well as by the various prophecies in the New Testament of the evils reserved for the latter days.

The attitude is already explicitly found in the patristic age. “I do not issue commandments to you like a Peter or a Paul,” wrote St Ignatius of Antioch to the Romans at the start of the 2nd century — “they were free men while I even until now am a slave.” Writing to the Church of Neocaesarea in the year 368 to commiserate with them on the death of their holy bishop Musonius, St Basil the Great wrote:

A man has passed away who was quite manifestly far superior to his contemporaries… He showed forth the ancient character of the Church, so that those who spent time with him seemed to be in the company of one of those men who shone like stars two hundred years and more ago. (Letter 28)

The same attitude finds startling and enigmatic expression in a saying attributed to St Ischyrion, one of the Fathers of the Desert:

The holy Fathers were making predictions about the last generation. They said, “What have we ourselves done?” One of them, the great Abba Ischyrion replied, “We ourselves have fulfilled the commandments of God.” The others replied, “And those who come after us, what will they do?” He said, “They will struggle to achieve half our works.” They said, “And to those who come after them, what will happen?” He said, “The men of that generation will not accomplish any works at all, and temptation will come upon them; and those who will be approved in that day will be greater than either us or our fathers.”2

Some words of St Thomas Aquinas may be instructive here. He writes:

The final consummation of grace came about through Christ, and so His time is called “the fullness of time.” Consequently, those who were closer to Christ, whether before, like John the Baptist, or after, like the apostles, knew the mysteries of faith more fully. We see the same thing in regard to the condition of a man, who has perfection in youth, and a man is the more perfect in proportion as he is close to youth, whether before or after. (Summa Theologiae, 2a 2ae 1. 7 ad 4)

In other words, implies the angelic doctor, as part of the honour due to Christ, the average level of grace and spiritual perception among mankind will be greater in proportion to our nearness to the time of His first coming. Elsewhere he writes: “As to the faith in Christ’s incarnation, it is evident that the nearer men were to Christ, whether before or after Him, the more fully, for the most part, were they instructed on this point, though after Him more fully than before” (2a 2ae, 174. 6). This offers us another reason why the restorationist attitude of looking to the past in religious matters and deriving inspiration from it is particularly appropriate for the Christian.

Finally, a brief response to the objections:

To the first: The great 17th-century Jesuit, Cornelius a Lapide, quotes a confrere of his who said that the reason it is foolish to ask “why are former times better than these” is that it’s obvious why they are; it’s because all created things have a tendency to decline. So, it’s foolish even to raise the question! But Cornelius himself prefers to see the verse from Ecclesiastes as above all a practical admonition rather than a speculative principle: the Holy Spirit is warning us against that kind of idle peevishness that prefers to praise the past rather than to make the most of the opportunities afforded to us in the present.

To the second: St Augustine is replying to the question of why God did not become incarnate from the beginning. The various ages of the human race that he has in mind, each with its proper beauty, are not periods within the life of the Church, but the different covenants of God with mankind: his covenant with Noah, with Abraham, with Moses, and so on, till the new and everlasting covenant through Christ. But even if we go on to apply his words to the life of the Church, they would not be contrary to our thesis: for the beauty of the various periods of the Church lies especially in the different saints whom God raises up to fight against spiritual entropy.

To the third: Although human nature is no more infected by original sin at one period than another, the very fact of original sin means that actual sins tend to increase, and to press down on mankind with a greater weight, as history proceeds.

To the fourth: The law of entropy does not of itself allow us to predict the future of the human race with any confidence, especially as God remains always free to do new things. But Chesterton elsewhere vigorously expresses the perpetual need for restoration in the words that he puts into the mouth of King Alfred, at the end of The Ballad of the White Horse:

Will ye part with the weeds for ever? Or show daisies to the door?

Or will you bid the bold grass go, and return no more? …

Over our white souls also, wild heresies and high

Wave prouder than the plumes of grass, and sadder than their sigh. …

And though skies alter and empires melt, this word shall still be true:

If we would have the horse of old, scour ye the horse anew.

The Case for Liturgical Restoration: Una Voce studies on the Traditional Latin Mass (Angelico Press, 2019), p. 14.

The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, tr. Benedicta Ward (MacMillan, 1980), 111.

Absolutely fabulous engagement. Thank you for addressing this so systematically.

Thank you, Father. For the past couple of years I've been immersed in Catholic books from before 1970. There is some excellent content therein; however, there are also assumptions about the culture that are now gone and never coming back. That goes both for the laity and clergy. In a book of short stories by J.F. Powers, for instance, we get glimpses into the common and parish life of the secular clergy that do not reflect a comparable life today. Instead of multiple priests for one parish, today it is usually one priest for multiple locations. (Not the case as much for religious priests or the SSPX.) On the other hand, I daresay that the celebration of the traditional Mass is undoubtedly more reverent than it often was in days past--there is rarely the situation of say six Masses on a Sunday and communion distributed outside the Mass to the throngs of Catholics who took their faith and accompanying obligations seriously. I know that amongst the Orthodox the notion of restoration is especially strong due to its being tied to national identity. The Russian restorationists hearken back to "holy Russia" of the 19th century, overlooking the fact that outside the well-known lavras, the priests and clergy in the hinterlands were often ill-treated, poor, ignorant, and their holiness dubious. Sure, it was the age of The Way of the Pilgrim and rebuilding of Mount Athos, but many of the common people were appallingly ignorant and superstitious and the upper classes increasingly infected by Western secularism. Let the dead bury the dead and let us deal with the problems at hand.