St. John Henry Newman: Father of Vatican II—or Godfather of the Traditionalist Movement? (Part 2)

In the first part, I began my overview of Newman’s “traditionalism.” Today, I continue with several telltale passages from his writings — passages that could never have been written by a liberal, a progressive, or a modernist. On the contrary, as we will see, Newman had a particular knack for putting his finger on just what is wrong with “the religion of the day,” the fashionable or “aggiornamento’d” version of Christianity.

Ancient Israel as a Model and Warning

In my opinion, one of Newman’s greatest strengths as a biblical exegete is his keen sense, indebted to the Church Fathers, that the Old Testament is not just a record of a particular ancient people or nation, but a mirror we hold up to our faces to see our own image. The virtues of Israel are the virtues of Christians, and their vices our vices.

A splendid example of his approach is the following passage, in which he explains that it would make no difference to have miracles, if we have not faith and love, illustrating the more general (and uncomfortable) truth that Christianity does not somehow automatically make us better people than the ancient Israelites. It gives us more access to truth and grace—that is all. We can still imitate their disbelief, even as the best of them foreshadowed our saints and are counted among our saints.

What is the real reason why we do not seek God with all our hearts, and devote ourselves to His service, if the absence of miracles be not the reason, as most assuredly it is not?

What was it that made the Israelites disobedient, who had miracles? St. Paul informs us, and exhorts us in consequence. “Harden not your hearts, as in the provocation, in the day of temptation in the wilderness ... take heed ... lest there be in any of you” (as there was among the Jews) “an evil heart of unbelief in departing from the Living God.” Moses had been commissioned to say the same thing at the very time; “Oh that there were such a heart in them, that they would fear Me, and keep My Commandments always!”

We cannot serve God, because we want the will and the heart to serve Him. We like any thing better than religion, as the Jews before us. The Jews liked this world; they liked mirth and feasting. “The people sat down to eat and to drink, and rose up to play;” so do we. They liked glitter and show, and the world’s fashions. “Give us a king like the nations,” they said to Samuel; so do we. They wished to be let alone; they liked ease; they liked their own way; they disliked to make war against the natural impulses and leanings of their own minds; they disliked to attend to the state of their souls, to have to treat themselves as spiritually sick and infirm, to watch, and rule, and chasten, and refrain, and change themselves; and so do we. They disliked to think of God, and to observe and attend His ordinances, and to reverence Him; they called it a weariness to frequent His courts; and they found this or that false worship more pleasant, satisfactory, congenial to their feelings, than the service of the Judge of quick and dead; and so do we: and therefore we disobey God as they did,—not that we have not miracles; for they actually had them, and it made no difference.

We act as they did, though they had miracles, and we have not; because there is one cause of it common both to them and us—heartlessness in religious matters, an evil heart of unbelief; both they and we disobey and disbelieve, because we do not love.1

In a similar vein, Newman speaks of how even the incarnate Christ remains the “hidden Savior” of Israel, one whose presence calls for reverential fear and faith in things unseen. We can quarrel and commit blasphemy towards Christ just as the Jews of His day did:

If He is still on earth, yet is not visible (which cannot be denied), it is plain that He keeps Himself still in the condition which He chose in the days of His flesh. I mean, He is a hidden Saviour, and may be approached (unless we are careful) without due reverence and fear. I say, wherever He is (for that is a further question), still He is here, and again He is secret; and whatever be the tokens of His Presence, still they must be of a nature to admit of persons doubting where it is…. And when they come to think him far away, of course they feel it to be impossible so to insult Him as the Jews did of old; and if nevertheless He is here, they are perchance approaching and insulting Him, though they so feel. And this was just the case of the Jews, for they too were ignorant what they were doing. It is probable, then, that we can now commit at least as great blasphemy towards Him as the Jews did first, because we are under the dispensation of that Holy Spirit, against whom even more heinous sins can be committed…2

Church Services Too Long, In Need of Modification?

Newman sees the liturgical services (or, as he calls them, “ordinances”) of the Church as an opportunity to test our actual resolve to be holy, to attend in faith and love to God’s hidden presence. If we cannot bring ourselves to go to church at a set time to meet the Lord and to concentrate our minds on Him when the means are provided to us, why should we presume that we will succeed in putting our minds on Him elsewhere, when no consistent means are given for doing so?

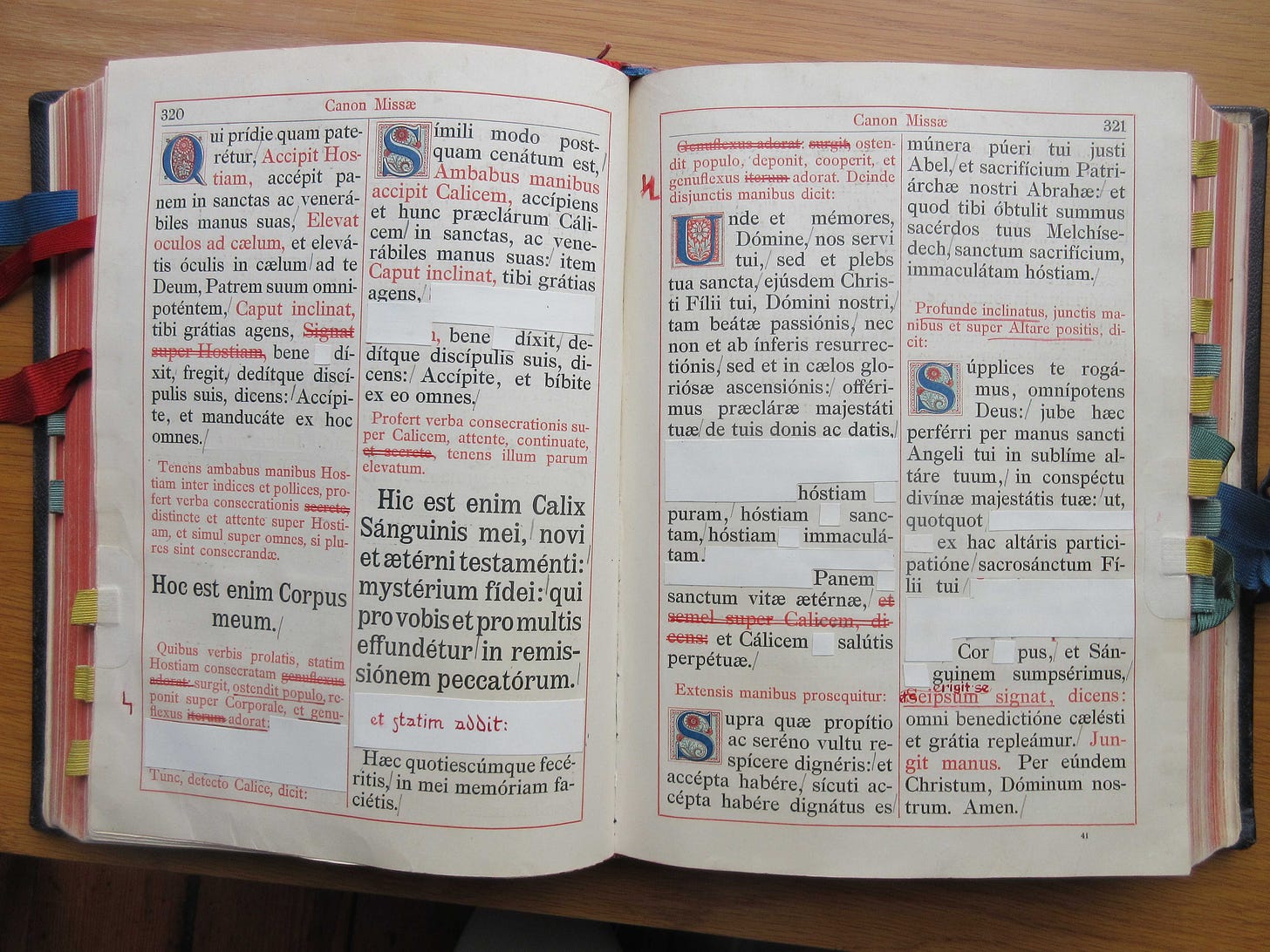

Back in Newman’s day, proposals were afoot for shortening and simplifying the Church’s public worship, and he opposed them staunchly. As we know, one of the principal goals of twentieth-century liturgical reform in the Catholic Church was to abbreviate all the ceremonies, because they were considered too long for “Modern Man.” This tendency was at work in Pius XII’s Holy Week deformation before the epitome of exiguity was achieved in the hieratic haiku of the rites of Paul VI. Newman has something helpful to say to this self-sabotaging reformism:

If any one alleges the length of the Church prayers as a reason for his not keeping his mind fixed upon them, I would beg him to ask his conscience whether he sincerely believes this to be at bottom the real cause of his inattention? Does he think he should attend better if the prayers were shorter? This is the question he has to consider. If he answers that he believes he should attend more closely in that case, then I go on to ask, whether he attends more closely (as it is) to the first part of the service than to the last; whether his mind is his own, regularly fixed on what he is engaged in, for any time in any part of the service?

Now, if he is obliged to own that this is not the case, that his thoughts are wandering in all parts of the service, and that even during the Confession, or the Lord’s Prayer, which come first, they are not his own, it is quite clear that it is not the length of the service which is the real cause of his inattention, but his being deficient in the habit of being attentive. If, on the other hand, he answers that he can fix his thoughts for a time, and during the early part of the service, I would have him reflect that even this degree of attention was not always his own, that it has been the work of time and practice; and, if by trying he has got so far, by trying he may go on and learn to attend for a still longer time, till at length he is able to keep up his attention through the whole service.3

Newman insists we should trust the words handed down by tradition:

Let us compose ourselves, and kneel down quietly as to a work far above us, preparing our minds for our own imperfection in prayer, meekly repeating the wonderful words of the Church our Teacher, and desiring with the Angels to look into them.4

Newman makes particular mention of the Lord’s Prayer, which for him exemplifies the value of simple, clear, unemotional, formal prayer:

Christ gave us a prayer to guide us in praying to the Father; and upon this model our own Liturgy is strictly formed…. [T]here is ever a call upon us for seriousness, gravity, simplicity, deliberate trust, deep-seated humility. Many persons, doubtless, think the Church prayers, for this very reason, cold and formal. They do not discern their high perfection, and they think they could easily write better prayers. When such opinions are advanced, it is quite sufficient to turn our thoughts to our Saviour’s precept and example. It cannot be denied that those who thus speak, ought to consider our Lord’s prayer defective; and sometimes they are profane enough to think so, and to confess they think so.5

Remarkable words, in light of Pope Francis’s audacity in rewriting the end of the Lord’s Prayer (something a lot of people probably don’t even remember now—there was so much trauma during those twelve years).

As a matter of fact, Newman insists that major changes to liturgical rites will undermine religion. His words are positively haunting against the backdrop of the freefall in Catholic statistics over the past six decades:

Granting that the forms [of worship] are not immediately from God, still long use has made them divine to us; for the spirit of religion has so penetrated and quickened them, that to destroy them is, in respect to the multitude of men, to unsettle and dislodge the religious principle itself. In most minds usage has so identified them with the notion of religion, that the one [the rites] cannot be extirpated without the other [the religion].6

Along similar lines, Newman preached on the quality of zeal that befits the confessor of Christ, and complained quite movingly of coreligionists who dared to suggest purging verses from the Psalms because they were no longer fitting to recite. We pick up the thread where he is telling us how much we are supposed to keep learning from the Old Testament. Watch where he goes with the Psalter:

A certain fire of zeal, showing itself, not by force and blood, but as really and certainly as if it did—cutting through natural feelings, neglecting self, preferring God’s glory to all things, firmly resisting sin, protesting against sinners, and steadily contemplating their punishment, is a duty belonging to all creatures of God, a duty of Christians, in the midst of all that excellent overflowing charity which is the highest Gospel grace, and the fulfilling of the second table of the Law.

And such, in fact, has ever been the temper of the Christian Church; in evidence of which I need but appeal to the impressive fact that the Jewish Psalter has been the standard book of Christian devotion from the first down to this day. I wish we thought more of this circumstance. Can any one doubt that, supposing that blessed manual of faith and love had never been in use among us, great numbers of the present generation would have clamoured against it as unsuitable to express Christian feelings, as deficient in charity and kindness?

Nay, do we not know, though I dare say it may surprise many a sober Christian to hear that it is so, that there are men at this moment who (I hardly like to mention it) wish parts of the Psalms left out of the Service as ungentle and harsh? Alas! that men of this day should rashly put their own judgment in competition with that of all the Saints of every age hitherto since Christ came—should virtually say, “Either they have been wrong or we are,” thus forcing us to decide between the two. Alas! that they should dare to criticise the words of inspiration! Alas! that they should follow the steps of the backsliding Israelites, and shrink from siding with the Truth in its struggle with the world, instead of saying with Deborah, “So let all Thine enemies perish, O Lord!”7

Yet Paul VI did exactly what Newman railed against: he had “parts of the Psalms,” hundreds of verses, “left out of the Service” (that is, the Liturgy of the Hours of 1970), following the steps of the backsliding Israelites.8

I would go further and say that Newman, of all modern theologians, is the one whose thought stands most opposed, as a matter of principle, to the postconciliar liturgical reform.

There never was a time since the apostles’ day when the Church was not; and there never was a time but men were to be found who preferred some other way of worship to the Church’s way. These two kinds of professed Christians ever have been—Church Christians and Christians not of the Church; and it is remarkable, I say, that while, on the one hand, reverence for sacred things has been a characteristic of Church Christians on the whole, so, want of reverence has been the characteristic on the whole of Christians not of the Church.9

Did those who radically altered the inherited liturgy, with its profound spirit of reverence exhibited and inculcated in a thousand turns of phrase, bows of the head, kisses of the altar, bending of the knees—did they “prefer some other way of worship” to what had been, for so many centuries, “the Church’s way”? Did they show “reverence for sacred things” or rather an appalling “want [that is, lack] of reverence”? As if continuing his train of thought, Newman says in a different sermon:

It is scarcely too much to say that awe and fear are at the present day all but discarded from religion. Whole societies called Christian make it almost a first principle to disown the duty of reverence; and we ourselves, to whom as children of the Church reverence is as a special inheritance, have very little of it, and do not feel the want of it.10

How much more do these words apply to us, almost two hundred years after he preached them!

Next week, this series will conclude with Newman’s thoughts on churches, worldliness, Holy Communion, sacramental coherence, the gravity of sin, and trust in Divine Providence—a virtue we all very much need to cultivate, at a time when renegade churchmen on the one hand and pessimistic nay-sayers on the other work almost in tandem to undermine our fidelity.

Parochial and Plain Sermons, vol. 8, sermon 6, Miracles no Remedy for Unbelief.

Parochial and Plain Sermons, vol. 4, sermon 16, Christ Hidden from the World.

Parochial and Plain Sermons, vol. 1, sermon 11, Profession without Hypocrisy.

Ibid. If someone were to object that my citations here are from sermons preached while Newman was an Anglican, it will suffice to reply that he very particularly sought to have all of these sermons republished years after he became Catholic, with no modifications made to them. In other words, the truths he had already recognized then were truths that he embraced even more fully as a Catholic.

Parochial and Plain Sermons, vol. 1, Sermon 14, Religious Emotion.

Parochial and Plain Sermons, vol. 2, Sermon 7, Ceremonies of the Church.

Parochial and Plain Sermons, vol. 3, sermon 13. Jewish Zeal, a Pattern for Christians.

For a full listing of the omitted verses, see my article “The Omission of ‘Difficult’ Psalms and the Spreading-Thin of the Psalter,” Rorate Caeli, November 15, 2016.

Parochial and Plain Sermons, vol. 8, sermon 1, Reverence in Worship.

Parochial and Plain Sermons, vol. 5, sermon 2, Reverence, a Belief in God’s Presence.

Thanks for these wonderful essays. Yes, Newman is a great man for our times…a Prophet for our confused times. He expresses truths in such a clear way. He may seem cold to some, but I always feel a warmth seeping through all his writings…almost as if he were writing about something he LOVED, and wants me to love too!!!!

If Newman, even as an Anglican, understood all these things to be correct, how painfully would he tear strips into the hierarchy for doing exactly as he warned.