The Mass and the Missions, Part II: A Requiem for Father Willie Doyle

One of the most saintly and heroic military chaplains of modern times

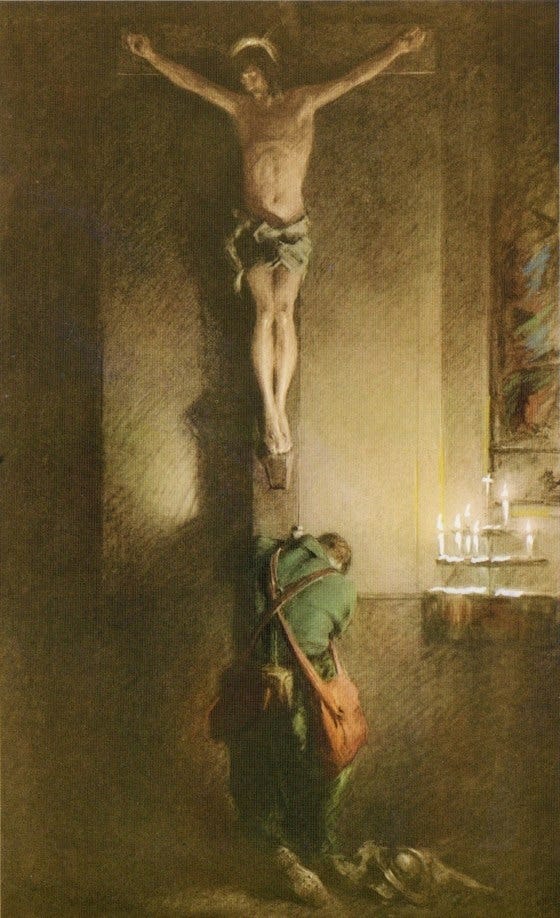

He was a man among the dead, a “curé of a parish of trenches,” a missionary on the threshold of hell. Surrounding him were the shattering blast, the piercing whine of shot and shell, the spit and rattle of machine gun fire, and everywhere, unceasingly, the agonized cries of the wounded and dying. Yet, amid the terror and stench of war, the waste and phenomenal loss, Fr. William Doyle’s heart rested in unspeakable peace, even as the Sacred Host rested in his hands. He leant over his makeshift altar made in the side of the trench, a doorway to eternity cut out of a living grave. Requiem aeternam dona eis Domine: et lux perpetua luceat eis. He whispered the prayer over and over again, gently shepherding his flock of departed souls, the sole man of peace in a world consumed by war. It was September 9, 1916, and he offered the Holy Sacrifice as the battle of the Somme raged all around him.

He wrote of that day,

By cutting a piece out of the side of the trench, I was just able to stand in front of my tiny altar, a biscuit box supported on two German bayonets. God’s angels, no doubt, were hovering overhead, but so were the shells, hundreds of them, and I was a little afraid that when the earth shook with the crash of the guns, the chalice might be overturned. Round about me on every side was the biggest congregation I ever had: behind the altar, on either side, and in front, row after row, sometimes crowding one upon the other, but all quiet and silent, as if they were straining their ears to catch every syllable of that tremendous act of Sacrifice—but every man was dead! Some had lain there for a week and were foul and horrible to look at, with faces black and green. Others had only just fallen, and seemed rather sleeping than dead, but there they lay, for none had time to bury them, brave fellows, every one, friend and foe alike, while I held in my unworthy hands the God of Battles, their Creator and their Judge, and prayed to Him to give rest to their souls. Surely that Mass for the Dead, in the midst of, and surrounded by the dead, was an experience not easily to be forgotten.1

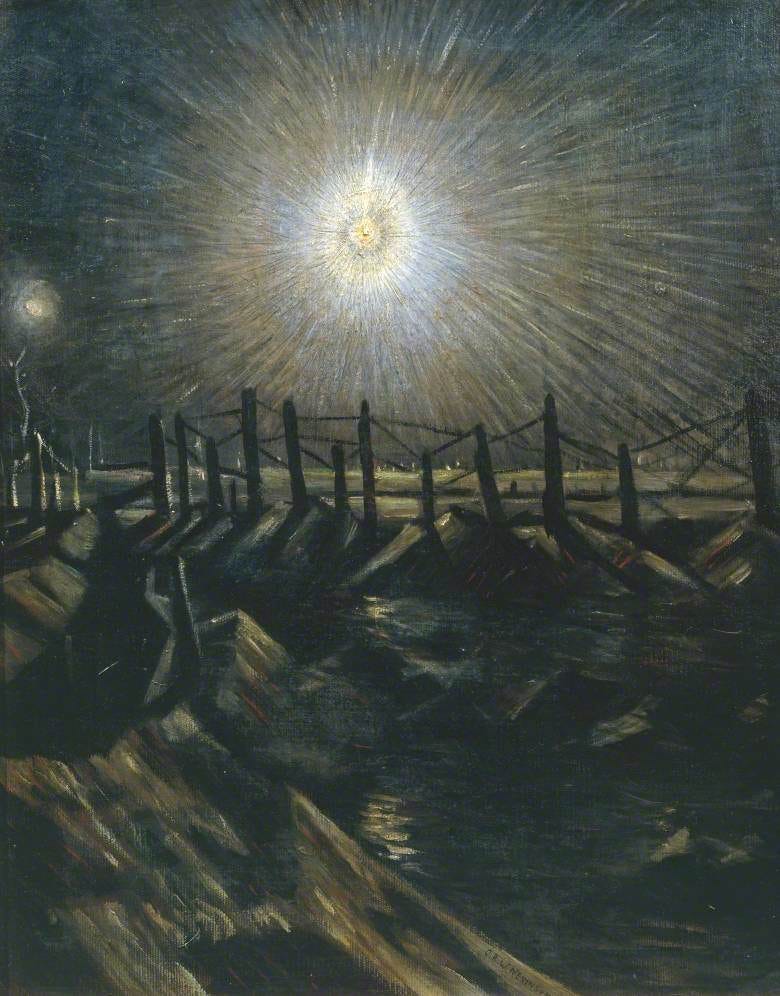

Fr. Willie would follow his lost sheep to the very depths, he would break the prison of night. Was he not a son of Loyola? In the great horrific landscape of war, the vast killing fields, death bursting upon his men in the darkness, was the unveiling of the eternal battle, the titanic struggle between the two standards: Christ the King and Lucifer, “the mortal enemy of our human nature.”

He had made a personal vow in 1911:

Can a Jesuit who deliberately refuses his Lord any act of self-denial, which he knows is asked from him, ever be really insignis [distinguished, outstanding]? Will Jesus be content with only half-measures from me? I feel He will not; He asks for all. My Jesus, with Your help, I will give You all.2

In the eyes of the missionary of the trenches, the misery of man was transfigured by the Eternal Sacrifice, offered there on the biscuit-box altar amid the roar of guns. In the priest’s hands was the secret to the peace the world could not give, Christ, who came “to reconcile all things unto himself, making peace through the blood of his cross, both as to the things that are on earth, and the things that are in heaven” (Col. 1:20). Amid the infernal hell of the First World War, Fr. Willie went forth fearlessly to weal or woe, gladly offering his life that he might usher into heaven a mighty host, a company of soldiers for Christ, the eternal Prince of Peace.

A Soldier’s Training

He was a Dublin boy through and through, a lover of pranks, imperturbably cheerful, known more in youth for his jokes than for his piety.3 However, as one witness recounted, when the lad Willie set his mind to something, “nothing would deter him from carrying it through.” That determination brightened and clarified into white-hot spiritual intensity at the time of his Tertianship in the Jesuit Order during the transformative year of 1908. He then began to feel an insatiable calling to refuse Christ nothing, down to the smallest details of his daily routine. He took the motto of St. John Berchmans as his own, Communia non communiter: Common things uncommonly well.4

He began with breakfast. He renounced butter on bread and sugar in his tea, commencing a methodical daily battle for self-conquest waged over lukewarm plates and dry toast. In each jaunty attempt to smile when making a sacrifice, no matter how pathetic, he raised the ineffable Irish understatement to the level of supreme spirituality.

Father Willie’s ardor for Christ and for more intense sacrifices grew. In prayer, he felt Christ in the Tabernacle calling him to give up all personal indulgence. He believed he was being prepared interiorly and exteriorly by God for martyrdom in the Congo mission. Nights would find him kneeling in adoration before the Blessed Sacrament, or standing up to his chest in a freezing pond, or walking barefoot to a distant chapel. He wore a hairshirt and developed an ardent discipline of the present moment, taking as his model the Curé of Ars. Father Willie wrote in his diary, “Including confessions I was able one night to pass eleven hours with Jesus—telling Him every five minutes I was going after five more.”5

Through it all, he performed the ordinary duties of his state in life6 with humility and patience. He was utterly devoted to St. Thérèse (as yet to be beatified).7 In 1911, he made a pilgrimage to France, and at her grave he placed himself entirely in her hands that she might make him a saint, and to her protection he consecrated his rule of life: “to give all and to refuse nothing.”8

At the heart of Fr. Willie’s intense efforts to rid himself of every comfort was his luminous regard for the Priesthood and the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. “Jesus is a victim,” he wrote, “the priest must be one also.”9 He wrote in one of his pamphlets, Vocations:

The life of a religious, like that of every other human being, must be a warfare to the end; they have their crosses and tribulations, and God, in order to sanctify them, often sends great trials and interior sufferings, yet through it all, deep down in the soul they have Christ’s most precious gift: “My peace I leave you, my peace I give you,” that peace of heart, a ‘continual feast,’ which the world knows not, nor can earthly pleasures bestow.10

Father Doyle understood that the battle for interior peace was to be won by countless hidden acts of self-denial, offered in union with Christ, the King upon the altar. With the sudden outbreak of World War in August 1914, he turned from his ambition to serve as a missionary in Africa and put in his application to serve as a military chaplain in the British Army. With characteristic humor and self-deprecation that masked his pain, Father Willie wrote in a letter:

Naturally, I have little attraction for the hardship and suffering the life would mean; but it is a glorious chance of making the ‘ould body’ bear something for Christ’s dear sake. However, what decided me in the end was a thought that flashed into my mind when in the chapel: the thought that if I get killed I shall die a martyr of charity and so the longing of my heart will be gratified. This much my offering myself as a chaplain has done for me: it has made me realize that my life may be very short and that I must do all I can for Jesus now.11

His eventual appointment to the 16th Division (8th battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers) at the end of 1915 meant an excruciating separation from his father. His via crucis, so long prepared by the hidden immolation of each day, had commenced. “Thank God,” he wrote, “at last I can say, I have given Him all; or rather, He has taken all from me. May His will be done.”12

Dies Irae

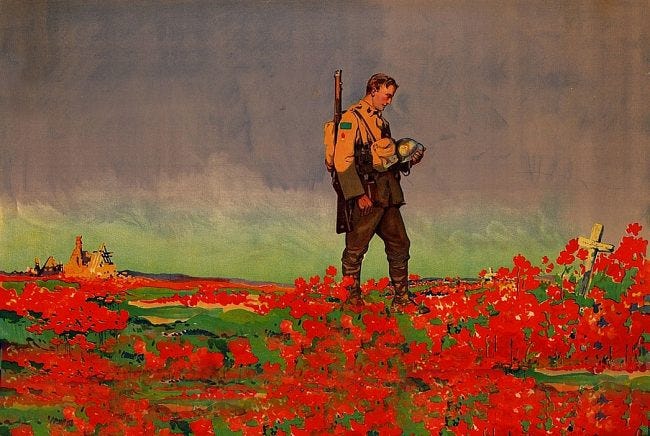

Father Doyle and his “brave boys” of the 8th battalion were thrust into the most deadly positions on the Western Front: Loos, Ginchy, and Messines. The continual rain of German shells and bullets, the endless marches, the boredom broken by sudden death—all became their daily bread, a poor supplement for soldiers’ rations.

A generation went to its doom. The kindly lamps of Christian Europe had all gone out, replaced by the red fire of machines in the night. Star shells illuminated ghastly scenes of the numberless dead, unburied where they lay amid the endless barbed wire and reeking craters. The very air was poison. Each night the world was dissolved in flames, and each morning found great hoards of men lying under blasted earth, reduced to dust and ashes. Often, enemies went to eternity locked in each other’s embrace, some in postures of rage, others in forgiveness and pardon.

For all that the poets sang of despair, still the common soldiers were men of great patriotism and endurance. In their humility was great heroism, and they would often recite Chesterton’s “Lepanto” between the trenches to bolster their courage. Father Willie loved with all his priestly heart these simple men, rough, but of earnest faith, his “Tommies,” and they in turn loved their “Padre,” venerating him to the point of believing that if he were with them, they would come to no harm. One soldier remarked to his fellows, “Isn’t the priest of God with us, what more do you want?”13

For all the horror and revulsion he felt at the destruction around him, Father Doyle was a man “Merry in God,” content to follow the Lamb, the Immortal victim, into the trenches, into no-man’s land, into enemy fire, into the very arms of death. The key to Father Willie’s cheerfulness in the face of annihilation lay in his undaunted love for Christ in the Blessed Sacrament, who, he wrote, “makes the hard things easy and the bitter things sweet.”14 It was the great paradox of Divine Love: immensity reduced to a cradle, death destroyed on the cross, the powers of the world forever shaken and turned upside down by the silent Host upon the altar.

The priesthood was the interior fire which impelled Father Doyle to the heights of heroism. “This is my vocation,” he wrote amid the horrible winter of 1917, “reparation and penance for the sins of priests; hence the constant urging of our Lord to generosity.”15 Imbued with love for the Living Sacrifice, the Jesuit chaplain could not be overcome by war’s terrors and hardships, though he bravely hid his human fear and hatred of its endless destruction, his teeth shaking through his smile. To Father Willie, all adversity was but a deeper and more joyous sounding of the first gift—to lay down his life for Christ the King.

The Chaplain’s Masses

Amid the endless round of battle and trench life, the Sacrifice of the Mass was the greatest consolation for Father Willie and his flock. The Mass atoned for sin and brought interior peace to men who were about to die; it obtained pardon and supplicated for the living and the dead. The Mass bound up in a single, perfect prayer each of the spiritual works of mercy, thus healing the ravages of war silently, imperceptibly, eternally.

Father Doyle’s Masses were said at great risk to himself, in some ruined chapel, out in the open, or, most often, in his trench dugout. His first Mass in the trenches was Easter Sunday, 1916.16 He recounted:

My church was a bit of a trench, the altar a pile of sandbags. Though we had to stand deep in mud, not knowing the moment a sudden call to arms would come, many a fervent prayer went up to heaven that morning.17

He spent many hours trudging through mud, rain and snow in order to reach his dispersed battalions, his dauntless energy and courage matched only by his love for His God and for souls.

I have celebrated Mass in some strange places and under extraordinary circumstances, but somehow I was more than unusually impressed this morning. The men had gathered in what was once a small convent. For with all their faults, their devil-may-care recklessness, they love the Mass and regret when they cannot come. It was a poor miserable place, cold and wet, the only light being two small candles. Yet they knelt and prayed as only our own Irish poor can pray, with a fervor and a faith which would touch the heart of any believer. They are as shy as children, and men of few words; but I know they are grateful when one tries to be kind to them and warmly appreciate all that is done for their souls’ interest.18

He described a memorable Candlemas celebrated in his dugout, which was capable of holding a dozen men. “But as my congregation numbered 46,” he wrote,

The vacant space was small. How they all managed to squeeze in I cannot say. There was no question of kneeling down; the men simply stood silently and reverently round the little improvised altar of ammunition boxes…Surely our Lord must have been glad also, for every one of the forty-six received Holy Communion, and went back to his post happy at heart and strengthened to face the hardships of these days and nights of cold.19

Father Willie carried his Mass kit with him over long and exhausting miles, taking great pains to offer the daily Sacrifice even if it was impossible for the ordinary soldiers or officers to attend. Quite apart from their presence, the awesome propitiatory nature of the Mass provided for the danger and itinerancy of their life. Palm Sunday 1917 found him celebrating the Mass alone, while his men made ready to continue their march through the Pas-de-Calais, as he recounted:

It was impossible to have Mass for the men in the morning, even though it was Palm Sunday, as there was much work to be done and we had to be off early. I got away to the little village and offered up the Holy Sacrifice for them, emptied a coffee pot, and fell into my place as the regiment marched off.20

He said Mass under enemy fire, on altars made of boxes and sandbags, often at one or two in the morning, after exhausting marches and days spent running over the battlefield giving absolution;21 he continually deprived himself of rest so that his men might have its secret, spiritual consolation while they slept.

At least once, Father Willie said Mass in a dugout that provided just enough shelter for him to offer the Sacrifice kneeling—a necessary relaxation in the rubrics that both preserved his life and fulfilled a secret longing of his heart. This Mass, said amid so much ruin, was, he humbly acknowledged, “I trust not unacceptable to Him.”22

To Free Their Souls

God indeed fructified the missionary labor of Father Willie Doyle. His harvest of souls was in a field without any consolation, his ministry a tree of life planted in the bloody rock of Mount Calvary. The eternal significance of the quest to deny himself all sensible pleasure, no matter how insignificant, was revealed in the dramatic daily struggle to provide the sacraments to the men of the 16th Division, a struggle requiring every ounce of his hard-won interior discipline, physical hardihood, and love for souls.

The Priest was the soldier of the God of Battles, of Christ the Captain, the Prince of Peace, who called him to wage unceasing war with the infernal powers. “Life,” Father Willie wrote, “is too short for a truce.”23 And in another place, he remarked:

armed with the weapons of his sacred calling, the priest is ever an instrument for good; but, strengthened by the power of great personal holiness, he becomes indeed a terror to hell.24

Fr. Willie “became all things to all men,” throwing himself into danger, experiencing so many near misses and miraculous deliverances from exploding shells that his Irish lads thought he was good luck, and would hide in his dugout. His reputation was enhanced by the fact that he often forgot to wear his helmet, which was of little use to him anyway in the service of the dying. Time and again, his physical endurance25 was stretched to the breaking point by days of deadly action with no rest.26

Viaticum and absolution brought incredible comfort to the Irish Catholics. Fr. Willie recounted:

Just before they marched at six in the evening, I gave the whole regiment—the Catholics, at least—a General Absolution. So the men went off in the best of spirits, light of heart with the joy of a good conscience.27

For all his good cheer, Father Doyle carried the traumatic loss of his beloved Tommies with him wherever he went. His was the pain of a true Father. He wrote,

As I came along the trench I could hear the men whisper, “Here’s the priest,” while the faces which a moment before had been marked with the awful strain of the waiting lit up with pleasure. As I gave absolution and the blessing of God on their work, I could not help thinking how many a poor fellow would soon be stretched and lifeless a few paces from where he stood; and though hardened by this time, I found it difficult to choke down the sadness which filled my heart. “God bless you Father, we’re ready now”, was reward enough for facing the danger, since every man realized that each moment was full of dreadful possibilities.28

Day and night, he ran into the thick of battle to anoint dying soldiers. The priest was to them a most consoling sight in their final moments. He described the death of one soldier:

“Ah, Father, is that you? Thanks be to God for his goodness in sending you; my heart was sore to die without the priest…” The Rites of the Church were quickly administered though it was hard to find a sound spot on that poor smashed face for the Holy Oils, and my hands were covered with his blood. The moaning stopped; I have noticed that a score of times, as if the very touch of the anointing brought relief. I pressed the crucifix to his lips as he murmured after me, “My Jesus, Mercy,” and then as I gave him the Last Blessing his head fell back, and the loving arms of Jesus were pressing to His Sacred Heart the soul of another of His friends, who I trust will not forget, amid the joys of Heaven, him who was sent across his path to help him in his last moments.29

In one unforgettable instance, Fr. Willie was called to run the gauntlet of machine gun fire in the snow to find a poor boy smashed into the corner of a trench, his legs broken and his life quickly fading. The priest wrote,

Then, while every head is bared, come the solemn words of absolution, “Ego te absolvo, I absolve thee from thy sins. Depart Christian soul, and may the Lord Jesus receive thee with smiling and benign countenance. Amen.” Oh! Surely the gentle Saviour did receive with open arms the brave lad, who had laid down his life for Him, and as I turned away, I felt happy in the thought that his soul was already safe in that land where “God will wipe away all sorrow from our eyes, for weeping and mourning shall be no more.”30

Harvest and Homecoming

Father Willie’s priesthood touched everyone who knew him. In a time of bitter political and religious controversy among his countrymen, he was a living embodiment of the One who called His followers friends. Often enough, the priest made friends of enemies by using whatever humble means lay at hand: cigarettes, a kind word, or a handkerchief, in which he gathered up and buried the remains of many a poor fellow known only to God.

He comforted captured German soldiers, tending their wounds, bringing them a drink, trying to “show them any little kindness I can…after all, are they not children of the same loving Savior who said, ‘Whatever you do to one of My least ones you do it to me’?”31 His Protestant fellow officers came to love and admire his courage and calm spirit in the midst of danger. The Irish Jesuit cradled the dying Ulsterman in his arms with the same tenderness with which he anointed his beloved fellow Catholics. This was no facile indifferentism, but the Charity that knows no fear, and it could not help but bear fruit in conversions32 among the living:

Though the life at times is rough and hard enough (at least the floor feels so at night) there are many consolations for a priest, not the least of which is the number of converts, both officers and men coming into the Church. Many of them have never been in contact with Catholics before, knew nothing about the grandeur and beauty of our religion, and above all have been immensely impressed by what the Catholic priests, alone of all the chaplains at the Front, are able to do for their men, both living and dying. It is an admitted fact, that the Irish Catholic soldier is the bravest and best man in a fight, but few know that he draws that courage from the strong Faith with which he is filled and the help which comes from the exercise of his religion.33

At the heart of Father Willie’s success with non-Catholics was “the grandeur and beauty of our Religion.” Our religion: the Mass, said in so many wretched hovels, with shrapnel flying over the altar; confession, which filled the faithful Catholic with the courage to die; absolution, which gave the soldier his final directive: “Depart Christian soul, and may the Lord Jesus receive thee with smiling and benign countenance”—a prayer Fr. Willie was sure “God gladly listens to and obeys, for He loves the priest whom He has chosen.”34

Fr. Willie with prophetic intuition had written of the priest’s mission of peace:

‘How beautiful on the mountains,’ says the Prophet, ‘are the feet of him who bringeth good tidings, and preacheth peace.’ Such are the feet of God’s Messengers of Love, ever ready to hasten to the beside of the sick and the dying, bringing hope and consolation, pardon and reconciliation to the sinful. In the morning, they ‘go unto the Altar of God,’ to offer the daily Sacrifice; they turn from the Tabernacle to the Seat of Mercy, the Confessional; by day and night they hurry through the streets in heat, and cold, and wet, for souls are ever crying out for the comfort they bear. They are often, like the Master’s feet, weary in the pursuit of sinners, seeking the lost sheep of the House of Israel; but the sound of their coming means the salvation and the snatching of God’s beloved children from the fires of Hell.35

In total devotion to this priestly mission, Father Willie laid down his life at the battlefield of Langemarck on the afternoon of August 16, 1917, struck by a German mortar blast as he administered last rites to a fallen soldier. He went to eternity a true “martyr of charity,” fulfilling the desire of his heart. He who had so tenderly buried the dead was himself quickly buried near the crossroads of Frezenberg, a grave soon lost amid the chaos of that fateful year.

He rests now, awaiting the final summons when he and the countless men whom he so faithfully prepared for heaven will rise together, a glad and victorious company. As a herald of that great day, he cries with trumpet voice,

The saints, from time to time, have made the dead body live again, knowing that it must one day crumble to dust, but the miracle of the priest is far greater, raising a dead soul and giving it an eternal life which can never end.36

Lux Aeterna

Father William Doyle, SJ, was nominated for the highest military honors of the British Army by those that knew and loved him, but he was never granted the award. The Jesuits in their turn received over 6,000 reports of favors answered through his intercession, from all parts of the world.37 However, his cause for canonization was forgotten in the mid-twentieth century, when Europe, weary of war and tired of the Faith, forgot the peerless chivalry he so brilliantly embodied. In our time, when realism prevails again, an association was formed and his cause was opened on November 20, 2022, fittingly at the Cathedral of Christ the King in Mullingar.

From eternity, Father Willie Doyle, like the Little Flower whom he loved so well, has not forgotten his spiritual children. If you find yourself in need of Father Willie’s hope, good humor, and (as he called it) “Celtic dash,” ask his intercession, and know that from Heaven as from the hell of the trenches, he will dare any darkness in order to bring you the peace of Christ. “Life is too short for a truce,” he says to the disheartened, the downtrodden, those suffering impossible circumstances. The principal scene of our struggle is not a smoking field in Belgium, but the present moment and the fragile altar of our own heart, where Christ in the Blessed Sacrament must reign for the renewal of the Church, the holy priesthood, and the world.

“Forward boldly, always forward,” as another soldier saint taught. Forward to sacrifice, forward to joy, forward to the Cross that conquers all fear, forward to the heavenly homeland, where a Kingdom awaits those who, in offering all to His Love, have washed their robes white in the Blood of the Lamb.

Ah, see the fair chivalry come, the companions of Christ!

White Horsemen, who ride on white horses, the Knights of God!

They, for their Lord and their Lover who sacrificed

All, save the sweetness of treading, where he first trod!These, through the darkness of death, the dominion of night,

Swept, and they woke in white places at morning tide:

They saw with their eyes, and sang for joy of the sight,

They saw with their eyes the Eyes of the Crucified.Now, whithersoever He goeth, with Him they go:

White Horsemen, who ride on white horses, oh, fair to see!

They ride, where the Rivers of Paradise flash and flow,

White Horsemen, with Christ their Captain: for ever He!38

Father Willie Doyle, pray for us!

Bibliography

Doyle, William. Pamphlets for the Faithful. Cenacle Press, 2023.

Doyle, William. To Raise the Fallen: A Selection of War Letters, Prayers, and Spiritual Writings of Fr. Willie Doyle, SJ. Edited by Patrick Kenny. Ignatius Press, 2017.

Doyle, William. Vocations. Os Justi Press, 2018.

O’Rahilly, Alfred. Fr. William Doyle S.J. Te Deum Press, 2020.

Alfred O’Rahilly, Fr. William Doyle, 315–16.

O’Rahilly, 179.

Despite the ordinariness of his boyhood, Fr. Willie even as a child had a unique tenderness for his forgotten neighbors. As a youth he took tea to the sick, and often would try to convince his fallen-away neighbors to receive the priest for confession.

For more information about his personal holiness and heroism, read this excellent article by Genevieve Rose Kwasniewski.

O’Rahilly, 270.

In Religion, Fr. Doyle served as a teacher and schoolmaster, then as a part of a traveling team of Jesuits who gave Parish missions and retreats. He produced a number of remarkable pamphlets on the Priesthood, which remain today among the most successful in their genre.

St. Therese of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face was beatified in 1915. The archives of Lisieux contain incredible testimonies about her appearances to soldiers during the War. These letters have been collected and published recently in a wonderful volume by Angelico Press.

Though suffering early in his Novitiate from a traumatic breakdown, there was not a trace of neurosis or perfectionism in the mature Fr. Willie. Defeat never deterred him, and he was the implacable enemy of all scruples. He did not simply bear the Cross; he embraced it with his distinctly Irish zeal and pluck.

O’Rahilly, 179.

Doyle, Pamphlets for the Faithful, 73.

O’Rahilly, 266.

O’Rahilly, 267.

O’Rahilly, 334.

O’Rahilly, 268.

O’Rahilly, 198.

A fateful day in Irish history.

O’Rahilly, 283

O’Rahilly, 332.

O’Rahilly, 333.

O’Rahilly, 339.

In 2018, New Liturgical Movement republished this fascinating photo essay of both Eastern and Western liturgies said at the front.

O’Rahilly, 391.

Doyle, To Raise the Fallen, 110.

Pamphlets, 127.

Father Willie was gassed multiple times. He refused a stove when the temperatures dropped for weeks below zero (he could never accept a comfort denied to his men). His feet were gashed and wounded from never taking off his boots. He kept himself in total preparedness, and when the call inevitably came, he would dash in bloody feet from his dugout to seek out the dying. In one famous act of charity, he slept an entire night with his face in the frozen trench mud so that his friend, a medical doctor who was suffering with fever, could sleep on his back.

He was consumed in the ministry of giving absolution and burying the dead, and often seen running the perilous course of the corpse-strewn battlefield with his shovel in hand. Father Willie quickly memorized the burial service, so that he could work at night without drawing the attention of the Germans.

O’Rahilly, 277.

O’Rahilly, 301.

O’Rahilly, 350–51.

O’Rahilly, 335.

O’Rahilly, 366.

He wrote, “One of my converts, received into the Church last night, made his First Holy Communion this morning under circumstances he will not easily forget. I see in the paper that 13,000 soldiers and officers have become Catholics since the War began, but I should say this number is much below the mark. Ireland’s missionaries, the light-hearted lads who shoulder a rifle and swing along the muddy roads, have taught many a man more religion by their silent example, than ever dreamed of before.” (O’Rahilly 379).

O’Rahilly, 306.

Pamphlets, 113.

Ibid.

Pamphlets, 126.

To Raise the Fallen, 30–31.

“Te Martyrum Candidatus,” by Lionel Pigot Johnson.

Thank you for this beautiful tribute to the amazing battlefield priest, Fr. Doyle. Much to love and admire. And emulate.

How embarrassing that I have not heard of Fr. Willy Doyle, SJ till today!

Less than halfway through, I said to myself, "Today's Society will never assign a Promoter of the Cause for this man's canonization - shame on them! "At least not till they retool his life so that the synodal crowd has something to embrace."

He's far too much a son of the Exercises. Far too Ignatian. That's what consoles me most about this narrative. Then, it breaks my heart. THE Ignatian spirit. THE Spiritual Exercises. They are right in the narrative. Hell. Christ, the Military Captain and the King. The Prayer for Generosity. The Degrees of Humility and the Types of Men. They are all here in the article, if one knows what he's looking at.

Thank you!

There he is. In the very shadow of the stinking memory of that Irish heresiarch George Tyrrell and of the fond and somewhat tragic memory of the faithful yet oft-misunderstood Dubliner-by-adoption, GM Hopkins'!

Speaking of the good Father Hopkins, though, the little things. The ordinary thing in an extraordinary way... like St. Alphonsus, SJ in Hopkins' poem. Like Father Willy.!

"The kind and merciful shepherd-of-a-priest has got to turn his back on his post that faces the altar of God," insists the cost-counting Worldling... and Father Willy, as you present him, makes a fool of the Worldling.

Thank you!