“We May Not Fully Understand…”: Reality Beyond Words

Or, Why It Is Better Not to Understand Everything Immediately — Part 1

I enjoy keeping my finger on the pulse of how the Catholic and secular media are reporting on the resurgence of traditional forms of Catholic life and worship. One can learn a lot by considering how other people see you from the outside. Often enough, they make mistakes, even occasional howling blunders, but I also find that they seldom fail to perceive, with a mingled respect and curiosity, something different, special, intriguing—something that is perceived as countercultural in a good way.

I think there’s more to it than “everyone roots for an underdog.” It seems that everywhere there is a thirst for meaning, for contact with reality, for self-transcendence, and it also seems that the modern world—especially thanks to the stranglehold of technology, the internet, constant communication and social media—thwarts that vital contact with original reality, that possibility of escaping from the prison of the self, that quest for ultimate meaning rather than ephemeral information. So whenever a newspaper or magazine or website runs a major story on the traditional Latin Mass, I sit up and take note.

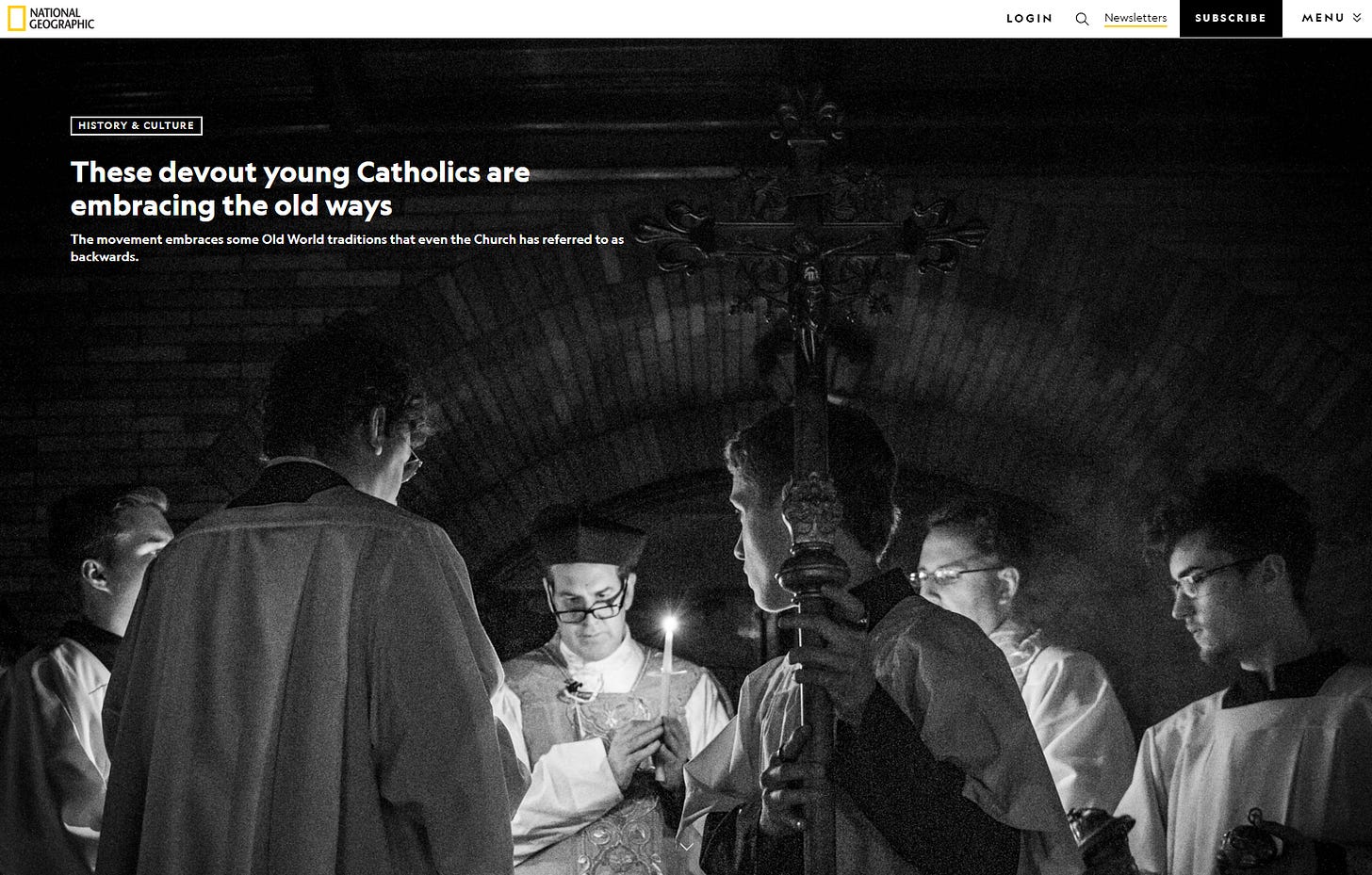

Just such an article appeared on October 26, 2023, in (of all places) National Geographic: “These devout young Catholics are embracing the old ways.” The subtitle brought a smile: “The movement embraces some Old World traditions that even the Church has referred to as backwards.” For cultural anthropologists, this must be like stumbling across Tutankhamun’s tomb! An observation by the author, Matthew Teague, caught my eye:

Each week traditionalists gather at more than 1,200 sites, mostly in the United States. They embrace a version of religious life that had drifted out of fashion—the “smells and bells” of previous generations—and reach for symbols and language that bewilder the outside world, and which the congregants themselves may not fully understand.

Is this last observation—that even folks in the pews (and perhaps—shall we admit it?—some clergy as well) don’t fully understand what they are seeing, hearing, saying, singing—meant as a criticism, or as a compliment? Or perhaps neither; could it be an implicit question about whether there might be a positive role for not understanding things fully?

I can’t help thinking of the remarkable words in the Byzantine Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, when the priest, right before consecrating the bread and the wine, prays:

You brought us forth from non-existence into being, and raised us up again when we had fallen, and left nothing undone, until You brought us to heaven and bestowed upon us Your future kingdom. For all this we give thanks to You, and to Your only-begotten Son, and to Your Holy Spirit, for all that we know and all that we do not know, the manifest and the hidden benefits bestowed upon us.

Let’s shift gears and look at this from another angle. Nowadays, the “slow movement” has really taken off. The reader has probably encountered phrases like slow food, slow wine, slow travel, slow reading, slow art, slow cinema, slow fashion, and even slow conversation (meaning, one in which each person is given the floor to say all that he or she wishes to say, without being interrupted—a technique that would be useful in many seminars at Great Books colleges!).

The basic idea is “a cultural shift towards slowing down life’s pace,” letting things take the time they need in order to be good or optimal or fulfilling or even, quite simply, human in scale. There are many ideas and personalities involved in this diffuse worldwide movement—many of them plainly contradictory—but I think it would be fair to say that, as a whole, it’s a reaction against the rationalism and utilitarianism of the modern industrial age. The ubiquitous model of mass-production—“delivering the goods,” whatever they are, as quickly and efficiently as possible—fails to distinguish between different kinds of goods and different ways of receiving them, how quickness and efficiency may affect their quality, and how, in general, the modern approach fails to take into account the diverse needs and abilities of individuals and communities.

In this post and in its two sequels, I’d like to make a pitch for “slow liturgy.” I will explain why our basic mental framework should not be capturable in the question, “What do I get out of the 60-minute Sunday Mass?,” but rather, “What will I get out of an entire lifetime of faithfully immersing myself in the mysteries of the Mass?” If liturgical reformers and church leaders make it their basic assumption that liturgy is to be assessed on the basis of what one can immediately understand in that 60-minute Sunday Mass, they are setting up the people of God for a catastrophic failure. They should be asking how a liturgy should be if it is to be capable of sustaining and rewarding an entire lifetime’s participation, so that it will be experienced less as a repetitious and burdensome duty and more as an ever-deeper entry into something both familiar and strange.

Justifying the revolution

In the heyday of liturgical reform, which was the decade from 1964 to 1974—and for many long decades thereafter—the avalanche of changes to Catholic worship was often justified by a few magical phrases that would be thrown about almost talismanically, with an air of infinite superiority to the meager mentalities of lowly laity. The leading contender was certainly the phrase “active participation,” which turned out to be quite ironic considering how many millions of people simply stopped going to church altogether (and therefore ceased to participate in any way), but along with that phrase, you’d often hear about “the needs of Modern Man,” “meeting people where they’re at,” “doing like the early Church,” and, what is of most interest to me at present, “greater accessibility.”

The revised liturgy was supposed to be, and was claimed and asserted to be, “more accessible,” but this is a monumental smokescreen if ever there was one. After all, nothing is more or less accessible in the abstract or without further qualification. One must always ask: “Accessible to whom? And giving access to what? And for the purpose of…?”

Almost exclusively, accessibility was understood as primarily or exclusively a verbal-conceptual phenomenon. If you can immediately grasp this bite-sized chunk of content, without further preparation, explanation, or remainder of bewilderment, then it’s considered to be accessible to you. The object of such immediate and complete comprehension obviously cannot be God, whom every orthodox theologian declares right off the bat to be incomprehensible; nor can it be man, who, as being made unto God’s image, is a mystery to himself; nor can it be the world, which is far too complicated and vast to fit into man’s mind, even if a thousand Einsteins were to chip away at it; nor can it be the mysteries revealed by God in history and delivered in Scripture, since each one of these is a combination of all of the above.

Therefore, a perfectly accessible liturgy, in the sense given above, would have to be about nothing, address no one, and lead nowhere.

This, admittedly, is a limit case fortunately never reached: there is always a residue of unintelligibility in anything human beings do, even if they are trying to avoid it. To the extent that any elements of traditional Christian liturgy remained intact, the incomprehensibility of God, of man, of the cosmos, and of the mysteries of Christ remained as well. Still, the reform introduced a fundamental tension between allowing the liturgy to be mysterious, as it must be, and trying, in the name of liturgical science, to purge it of the very features that tended to make it aweful, fearful, darksome, intricate, wondrous, and yet, paradoxically, also orderly and ordering, familiar and comforting, unassuming and free of invasive sources of irritation.

It seems to me that there is a mighty irony at work in the revival of the traditional Latin liturgy of the Roman church. In spite of all the hand-wringing of scholars and tinkerers about the horrible Middle Ages that led us into what Archbishop Bugnini called “lack of understanding, ignorance, and the ‘dark of night’ of a worship that lacks a face and light,”1 the irony is that new generations find the old rites in general quite sufficiently accessible, indeed more so than they find the new rites—provided one has a broader and deeper definition of “accessibility.”

The reason is not far to seek. The old liturgy appeals more consistently, more powerfully, to the full range of reality, natural and supernatural; of what it is to be human; of how we express ourselves, and what we are trying to express in words, gestures, songs, and quiet sighs. It appeals to all the senses, the various ages and temperaments and personalities, the different levels on which our interior life plays out and intersects with the external world.2

Non-verbal communication

The traditional Roman liturgy—and this is true of any of Christianity’s organically-developed apostolic rites—recognizes a truth on which psychologists never tire of discoursing: human beings primarily communicate non-verbally.

As a matter of fact, we are never not communicating something, even if we are not talking or have no intention of conveying a meaning. Orderliness and defentiality speak volumes, just as carelessness and casualness do. A liturgy, like any human ceremony, is constantly communicating through every word, stance, gesture, position, action, and silence. The old liturgy, by harnessing and regulating these things in a harmonious way to bring out their full interactive meaning, is more communicative; in that sense, it proffers more to access, and in more ways. The reformed liturgy, by eliminating traditional non-verbal language and then leaving so much to chance and idiosyncracy, thins the content and its delivery, while mingling it with extraneous and contradictory matter.

A video on body language by a former FBI agent, Joe Navarro, sharpened my awareness of the importance of small and non-verbal details in liturgy (and, therefore, the importance of being aware of them and being faithful to their proper execution). This expert looks at people from the point of view of an agent trying to assess potential threats, the trustworthiness of witnesses:

How we dress, how we walk, have meaning, and we use that to interpret what’s in the mind of the person. We are never in a state where we’re not transmitting information. We’re all transmitting at all times; we choose the clothes that we wear, how we groom ourselves, how we dress, but also how do we carry ourselves, are we coming to the office on this particular day with a lot of energy, or are we coming in with a different sort of pace… and what we look for are differences in behavior, down to the minutiae of: what is this individual’s posture as they walk down the street, are they on the inside of the sidewalk, on the outside, can we see his blink rate, how often he is looking at his watch… You can have a poker face, but you can’t have a poker body—somewhere it’s going to be revealed. We talk about non-verbals because it matters, because it has gravitas, because it affects how we communicate with each other. When it comes to non-verbals, this is no small matter. We primarily communicate non-verbally and we always will.3

Phrases like: “we primarily communicate non-verbally” and “we’re never not communicating something” are very relevant to the celebration of Mass. Every gesture—for example, the course and speed of movement around the altar; where, and when, the priest is standing or sitting; how he places his hands or bows his head; whether the priest’s gaze is directed out to the people or modestly downcast; how the sacred vessels are treated, and how the Blessed Sacrament is approached and handled—every gesture like this confesses what the celebrant, and the people, believe they are doing.

Why is it that the liturgical reformers seemed so tone-deaf or clueless about the most obvious things in life? Did they not realize that changing the bodily language, the gestures, postures, orientation, signs of veneration, custody of the eyes, would effect a sea change in mentality and spirituality? Or… was it that they understood perfectly well, and therefore abolished, piece by piece, a non-verbal language based in the Catholic Faith, substituting for it another with a contrary message?

Consider the well-documented loss of faith in the Real Presence of Our Lord. This was not an unfortunate result of a “lack of catechesis.” It was the intended result of a renovated catechesis. It was not an accidental byproduct of liturgical reform gone awry; it was a premeditated outcome of a new ecclesiology that identified the worshiping community with “the Body of Christ” and sought to oppose the supposed “fetishism” or “magic” of the Eucharistic cultus that had developed in the Church for at least a thousand years.

As Martin Mosebach points out:

An entire bouquet of respectful gestures had surrounded the sacrament of the altar, and these gestures were the most effective homily, which continually showed priests and faithful quite clearly the mysterious presence of the Lord under the forms of bread and wine. We can be certain: no theological indoctrination of so-called enlightened theologians has so harmed the belief of Western Catholics in the presence of the Lord in the consecrated Host as the innovation of receiving communion in the hand, accompanied by the abandoning of all care in the handling of the particles of the Host.

Yet can one really not receive communion reverently in the hand? Of course that is possible. Yet once the traditional forms of reverence were in place, exercising their blessed influence on the consciousness of the faithful, their discontinuation contained the message—and not just for the simple faithful—that so much reverence was not really necessary, and along with that there consequently grew the (initially unspoken) conviction that there was nothing there that demanded respect.4

Fr. Roberto Spataro makes a similar but broader point:

Humility is more than a virtue. It is the condition for a virtuous life. Watch the bows and genuflections the humble man makes faithfully before God in a spirit of obedience, acknowledging His merciful sovereignty, His love without bounds, His creative wisdom…. It [the old rite] turns to Him through the means of a sacred language differing from ordinary speech, because in the harmonious order of creation that the liturgy represents in its rituals, there is never a monotonous repetition or tedious uniformity, but a symphony of diversity, sacred and profane, without opposition, respecting the alterity of each. Here reason also renounces an excessive use of words that unfortunately exists in the liturgical praxis inaugurated by the Novus Ordo, interpreted by many priests as the opportunity for pure garrulousness. In the old rite, on the other hand, reason appeals to other dimensions of communication and, besides words pronounced or sung, also gives silence a place. This silence becomes the atmosphere, impregnated with the Holy Spirit, in which believing thought and prayerful word is born.5

What we do with our bodies, and even our refraining from speech at times, is just as communicative as what we say with our lips. The liturgy should therefore govern the motions and dispositions of our limbs and senses, harnessing them as symbols of truth and instruments of sanctification. This will help us to pray, to enter more deeply into communion with the Lord, and to yield ourselves to truths that cannot be put into words or captured in concepts.

As St. Paul says in the Epistle to the Romans, we should make our bodily members “instruments of righteousness”: “Neither yield ye your members as instruments of iniquity unto sin”—the sin of irreverence, of disrespect for holy things, of casual, haphazard, and inconsiderate behavior during our formal audience before the great King—“but present yourselves to God,” in theocentric worship that governs our self-presentation, “as those that are alive from the dead”—the living death of modern anti-natural, anti-Christic culture—“and your members as instruments of justice unto God” (Rom 6:13), the justice, namely, of the virtue of religion.

In the next part, we will show how Christianity thrives on the paradox of deeper participation through initial mystification, confrontation with difficulty, and unplanned breakthroughs.

Jeffrey Ostrowski, “A 1969 Quote.”

For example, on the relationship of children with the TLM, see Kwasniewski, Reclaiming Our Roman Catholic Birthright, 235–80.

Mosebach, Subversive Catholicism, 80–81.

Spataro, In Praise of the Tridentine Mass, 30.

Thank you for this wonderful article! Our "enlightened" age is taught to restrict understanding to the realm of the intellect, neglecting the role of the heart/spirit in apprehending the mysteries of life and of life's Creator. Rather than cultivating awe and wonder, we are trained to be uncomfortable with "things unknown."

It has always seemed to me that the emphasis on "active participation," understood as having to do/speak almost everything oneself, deprived many people of the ability to exercise "active listening," not only to what is said or sung, but to the actions done in conjunction with the texts (or in silence). This seems to mimic the radical Protestant Reformers, who barraged people with a multitude of words from the preacher (who, in effect becomes the mediator between the Word and man), while depriving them of any significant ceremonial because this was the surest way to change the beliefs of their congregants especially in regards to the "Lord's Supper": stay seated, pass a tray around, and the minister gets the left-overs for lunch. The bread and wine (juice?) are special because they are eaten together while thinking of Jesus -- the exact opposite of the fundamental truth that the people are special because they receive the Body and Blood of Christ in order to be transformed into his likeness.

What you wrote about the devolution of "the Body of Christ," into a reference to the congregation (a.k.a. the gathered community that MAKES Christ present) is true even among many who still retain a belief in the Real Presence of Christ in the Sacrament. I have heard this preached and taught many times. Churches should be stripped bare of imagery or even architectural beauty, so that the bodies of those present, who constitute the People of God, becomes the visual focus. This leads straight to the inadequate, if not outright heretical, understanding that the Eucharistic Body of Christ is primarily an affirmation of the individual's belonging: a right to which we are entitled simply by our presence, rather than an affirmation of our undeserved, active participation in the life of the Crucified and Risen Lord, which should be approached "with faith and in the fear of God." From that follow so many of the current disfigurations of theology, ecclesiology, and spirituality that can be seen in our time, even among hierarchy and clergy.

God forgive and correct me if I have mis-spoken.

I wrote a PhD dissertation on transubstantiation and I think it's clear that even very bright people who study original texts carefully and write about them "may not fully understand..." (in fact they typically have grave misunderstandings). Aristotle said something about bats, you may recall. We human beings are fitted out with intellects that can't help but be blinded by too much light. On the decline in belief in or respect for the Real Presence, it seems standard to point to communion in the hand. I think that practice should be repudiated, but what about other sociologically banalizing aspects of the reception of communion, namely, the "line 'em up pew by pew, everybody let's go" approach, and closely connected with that, the presumption in favor of 'frequent' (i.e., weekly, or every time you go to mass) communion? Did the loss of faith and reverence perhaps really start more with the reforms of Pius X, and communion in the hand is just the (or one) culmination of that movement towards banalization?