Ritual and Anti-Ritual: Cultic and Cultural Consequences

Seeking the most fundamental level at which to evaluate liturgy as such

At my parish, we are fortunate to have Solemn Mass most Sundays during the academic year. Each of these Masses reminds me anew, sometimes with an almost shattering power that brings me to tears, of one of the most basic reasons I love the traditional Latin Mass with all my heart.

For something to be a religious rite, to possess the quality of rituality, it has to have several properties.

First, it must come—and feel like it comes—from ageless depths, from time out of mind, from innumerable nameless ancestors (even if a few of them are named too).

Second, it must present itself as ever unchanging, always the same, semper idem. Its rituality precisely consists in the fact that it is predetermined; it is formulaic, controlled, and objective; a solemn act of offering that disposes its human ministers as mere servants. The ceremonies, the words uttered or chanted, the items employed, the ministers and their roles, are “set in stone,” year after year. The use of an ancient sacral language, with formulas that have not changed for eons, massively underlines this aspect.

Third, it must be obviously directed toward the Divinity: God is the one to whom the entire rite is being offered, from the man who is His priest, on behalf of the people for whom he mediates.

These properties are dramatically evident in the old Roman Rite. The moment you encounter it, you know you are up against something that comes from a different world, from across the ages, from fathers and forefathers. It is always the same in its structure and actions; you know what the antiphons and prayers and lessons of each day of the liturgical year will be. There is absolutely no room for the intrusion of novelty, spontaneity, creativity, or any other unbecoming swerve or surprise. It is like a giant river that moves irresistibly to the ocean and carries you with it.

This ritual, this rituality, brings peace. It reflects and restores order. It comes from and returns to the changeless God. It lodges deep in the soul and haunts the imagination. Its stability invites meditation and its quiet spaciousness invites prayer, without cajoling, hectoring, or pandering. It never once makes you the object or the priest the ringmaster. He is nothing but a servant who says and does what he is told to say and do. You are forgotten as you remember God.

The attempted replacement of the Roman Rite—the strange or novel order (Novus Ordo)—lacks all the above. We know it was produced by a committee in the 1960s and, sadly, feels like it. We know it’s full of options and variables, including the option to look traditional (to a point), albeit at the beck and call of the tasteful celebrant. The vernacular is our own contemporary lingo. The priest usually faces the people (which, all by itself, utterly destroys the rituality, since it no longer appears in any way to be a rite offered to God by a mediator on the people’s behalf). The texts and ceremonies of the day vary not only from church to church but even from Mass to Mass. There is little stability and no quiet spaciousness.

In short: anthropologically, phenomenologically, it is not a rite. Regardless of what is happening sacramentally, it has not the wherewithal to be a rite. It is “ritish,” that is, gestures at being a rite, rather like a recipe that doesn’t turn out. Between a true rite and a modern ritelet stretches a vast chasm, with no bridge from one side to the other.

Lately, I’ve been wondering if the single most important thing about the old rite is that it is indeed a rite, that is, something from time immemorial that is simply enacted by a priest who adds nothing to it. The new “rite” isn’t that at all; it is modern, polymorphous, and barely religious, since the essence of religion as a virtue is to offer adoration to God alone by means of sensible signs and sacred symbols.

As Dietrich von Hildebrand writes:

The new liturgy actually threatens to frustrate the confrontation with Christ, for it discourages reverence in the face of mystery, precludes awe, and all but extinguishes a sense of sacredness. What really matters, surely, is not whether the faithful feel at home at Mass, but whether they are drawn out of their ordinary lives into the world of Christ—whether their attitude is the response of ultimate reverence, whether they are imbued with the reality of Christ.1

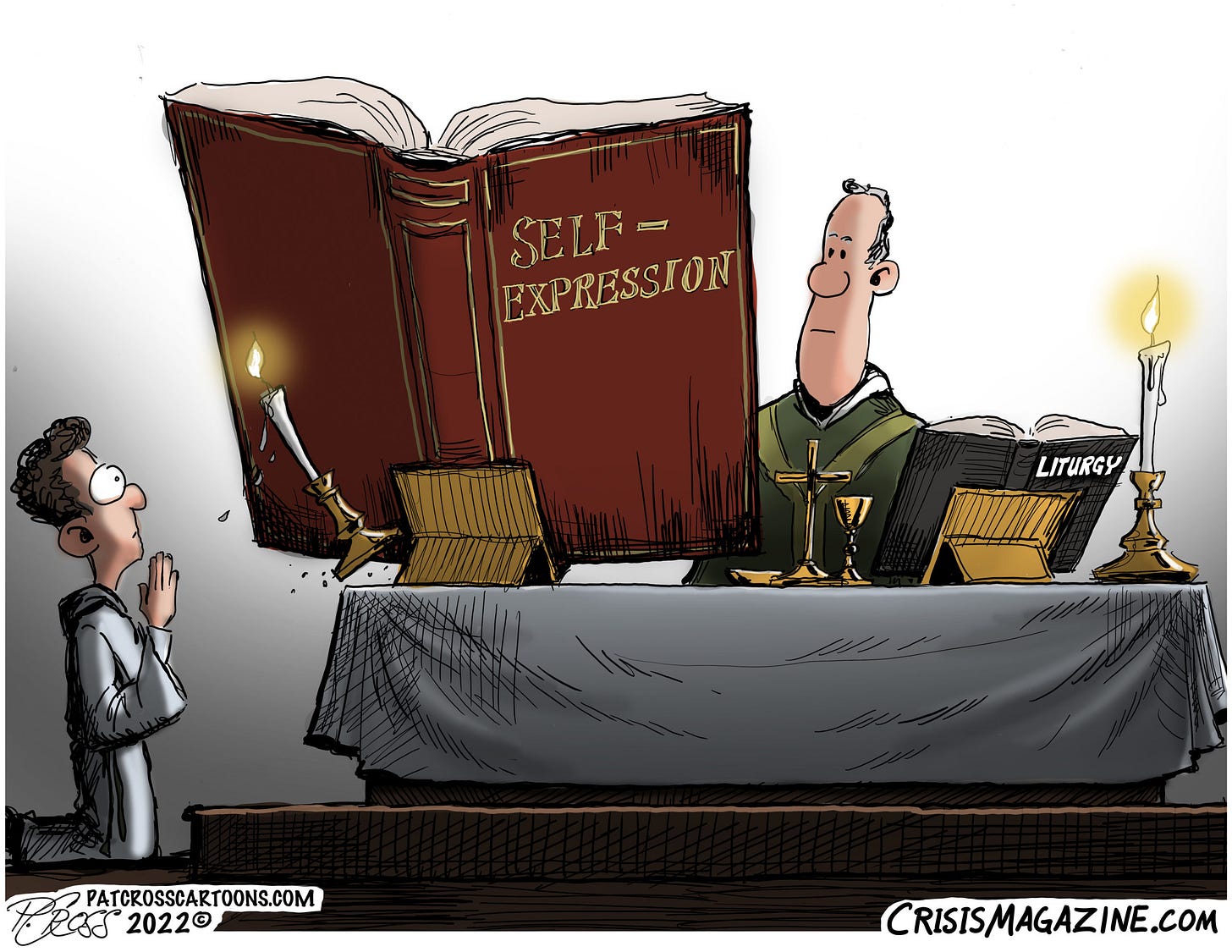

I enjoy reading ancient Far Eastern classics, because they express a resonance with the natural law that can be quite remarkable—somewhat like reading the Western Stoics or Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Confucius has a fairly well-developed notion of rites—what they are and how they should be conducted. Can you imagine what a classical Confucian sage would think of the two—the TLM and the Novus Ordo—if he were confronted with them? He would instantly recognize the difference between them, seeing the one as authentic selfless homage and the other as spurious self-expression.

In my Pints with Aquinas conversation, I talked about the successive “revelations” of prayer as I first discovered the Low Mass, then the High Mass, then the Solemn High Mass, and finally the Pontifical Mass. The points I’ve made in the foregoing paragraphs are more and more noticeable as you climb up the scale from the humblest form of the Roman Rite to its loftiest. It may not be easy for you to find a Solemn Mass, depending on where you live, but if there’s any way you can get to one, please make a point of doing it—even if it needs to be a special pilgrimage—and take in the sheer beauty, majesty, and order of the ritual, let them flow over you. It is an act of God and for God. That is why it rightfully claims our veneration. Archimandrite Boniface Luykx was compelled to admit:

A primary reason the faithful flock to the Tridentine Mass is their need for the reverence, holiness, and prayerfulness that emanate from the Presence of God in its very celebration. This Mass is a prayerful, true, and sacred ritual, a holy acting out of a mystery before the face of God, in holy language, and directly facing him. One feels in the Tridentine Mass a reaching out to the Holy One and a living contact with him, an opening-up to the unspeakably Sacred, expressed in symbols and rituals (of which the Novus Ordo was purposefully “cleansed”). This Mass has become so popular in America and Europe because it restores reverence as the primary “element” of celebration.2

I’m convinced that most Catholics who oppose the TLM or don’t understand “what’s the big deal” about it have not even begun to give themselves a chance to appreciate the qualities I’ve described, and thus, have not yet tasted the spiritual blessings they bring. But once you taste them, you can’t go back—and perhaps that is the unconscious fear all along, the fear of facing a mighty “parting of the ways.” This is the focus of the chapter called “The Grace of Stability” in my recent book, Close the Workshop: Why the Old Mass Isn’t Broken and the New Mass Can’t Be Fixed (pp. 306–28).

The traditionalist position on liturgy lacks coherence precisely when this aspect of the issue is underdeveloped, and in my experience, it usually is underdeveloped—namely, we are meant to worship in a rite, and Bugnini’s Mass is not a rite, strictly speaking. There is no evidence in Christian or pagan history for official, mature religious worship that is so dismissive of rituality, formality, ceremony, rubric, posture, sacred phraseology and chant.

Indeed, it would hardly be an exaggeration to say that the Bugnini Mass is an anti-rite, and furthermore, an anti-rite with a very long, nay, quintessentially medieval, tradition in Western Christianity. That tradition is called Carnival.

Here, I refer not to the festivities of Carnival themselves but to the underlying psychosocial phenomenon, such as we find analyzed in the work of Bakhtin. The fact that the New Mass does occasionally resemble a literal carnival is highly disturbing yet illustrative and thought-provoking. Even the less outrageous innovations (lay “ministers,” profane musical styles, the reversed altar, vernacularization, the pre-Communion handshake) are an emblem and a natural outgrowth of Carnival’s mundus inversus.

The essence of Carnival was permitting the dissolution of form, eschewing the constraints of social and religious ritual, deconstructing or inverting the established order of things, breaking free from the poetic-meditative state that flows from submission to realities—the seasons, the lifecycle of crops and livestock, the ill effects of gluttony, the social hierarchy, monogamous sexuality, etc.—that transcend the whims and appetites and preferences of the self. For, even in the very Catholic Middle Ages, a certain segment of the population seemed unable (or unwilling) to psychologically survive without periodically casting off and even violating the otherwise pervasive constraints of form and ritual. They lived illegally, irreligiously, once a year.

What modern scholars are more likely to overlook is that Carnival was part of a dualism—indeed, the defining psychosocial dualism of medieval culture. The opposing element in that dualism was the traditional Latin liturgy, which was the apotheosis of form and ritual, even as Carnival was the disintegration (in the worst case, the infernalization) of form and ritual.

Again, of course I am not saying that the New Mass is always carnivalesque in a sensationalistic, scandalous, overt sense. But the spirit of Carnival is there—indeed, Close the Workshop is an extensive and diverse demonstration that Bugnini’s liturgy is inseparable from the logic of aformality, of perpetual re-form, of personal rights over rites, of volition over submission, of spontaneity over solemnity, of casualness over sacral gravity, of expression over beauty, of difference over harmony, of liberty over stability.

For centuries, even after the Reformation, it was the Roman liturgy that opposed Carnival and kept it in check. Can we be surprised, then, at the appalling devastation that swiftly ensued when the liturgy began not to oppose but to reinforce the spirit of Carnival? Here’s how I put it in the aforementioned book:

It would be hard to deny that there are correlations between the character of the revised liturgical books, the customary crowd-oriented ars celebrandi, the lack of ascetical-mystical life among so large a part of the clergy, and the shallowness, if not heterodoxy, of preaching. All these things reinforce one another; there is little to oppose them from within the form of the liturgy itself.3

Carnival is an inherently unstable and destructive psychosocial force, and a carnivalesque liturgy creates a sort of positive-feedback loop in which the carnivalesque instincts that dominate secular life (especially modern secular life) are not attenuated but amplified by the people’s and the clergy’s experience at Mass. The results we see in the post-conciliar Church and world are what we would expect from a positive-feedback loop: rapid, catastrophic, system-wide failure (or what I described as “a Modernity trapped in its own death spiral”4).

Carnival is, quite literally and intentionally, nonsense; “the old rite abides far beyond all that nonsense.”5 Our work in assisting at, defending, and promoting the traditional liturgy—and a maximally formal, ritualistic, mystical-meditative celebration of it at that—is crucial to the restoration of the Church and even to the survival of Western civilization.

Quoted in Boniface Luykx, A Wider View of Vatican II: Memories and Analysis of a Council Consultor, 145. Read more about Luykx in my review essay of this memoir, and in two follow-ups (1, 2).

Luykx, 117–18.

Kwasniewski, Close the Workshop, 307.

Ibid., 32.

Ibid., 315.

Very well stated. That “carnival” state, when the new Mass was first introduced, caused me to leave the church for a long while. I still see it in Novus Ordo Masses - even those considered reverent. The entire structure is unreliable and always subject to change. It could be simply a raucous or enthusiastic rendition by the choir of some awful modern composition that ruins everything. I recall watching 2 young girls in front of me jumping up and down on the kneelers because they were so physically roused by the music. That’s the opposite of what we desire in the holy Mass. These kinds of things are all outward and tied to emotion, rather than devotion. You mentioned also the various Eucharistic ministers too. A Huge mistake on so many levels! Whenever I have the chance to attend the Vetus Ordo, I breathe a sigh of relief because I know what to expect. It’s always the same and that allows peace and depth of attention. I know I will not be jarred out of my mind by so many distractions and spiritual and psychological stress, if you could call it that. The old Mass is like a solid rock surrounded by swift rapids. It’s there to save me.

Years ago, while living in RI, I was asked for a variety of reasons to host Alice vonHildebrand at my home. She was invited (by Anthony Esolen, still there at the time) to give a talk at Providence College. [I'm happy to say that the hall for her talk was filled to capacity.] My point is that I took her to Holy Mass that morning at my local [unicorn] parish, where I was gratified for the opportunity to show her how beautiful a NO Mass could be. I was perplexed that she looked at very little (and may not have heard much either). Although a perfectly gracious guest in all things, she kept her head down and said nothing. Nothing at all.

Only now do I understand the difference between the rites, and how nothing--be it the reverent silence, the careful gestures on the altar, or the faith-filled movements for the reception of Holy Communion--could have made up for the paucity of the Mass itself. . And only now I wonder if she has helped to pray me away from my sober carnivale and into the Mass of the Ages.